经合组织各版本转让定价报告比较

19xx年 经合组织发表了第一份转让定价报告,题目为《转让定价与跨国企业》

该报告建议对于有形货物交易采用以下定价方法

(1) 可比非受控价格法

(2) 再销售价格法

(3) 成本加利润法

(4) 其他合理方法

19xx年经合组织发表了第二份转让定价报告,题目为《转让定价与跨国企业:三个税收问题》 该报告主要解决三个税收问题:

(1) 转让定价中的相应调整问题以及相互同意程序

(2) 跨国银行的税收问题

(3) 中心机构的管理和劳务费用的分配

19xx年7月,经合组织发表了题为《跨国企业和税务部门转让定价准则》(简称转让定价最后准则)的转让定价报告。

其主要目标是“帮助税务当局和跨国公司找到一个双方都能满意的办法,避免成本高昂的诉讼程序”。 19xx年经合组织的转让定价准则主要内容:

(1) 正常交易原则及其应用准则

(2) 转让定价方法及其应用准则

(3) 相互同意程序和相应调整

(4) 预约定价协议

(5) 转让无形资产需要特别考虑的因素

(6) 关于预约定价协议的相互同意程序

20xx年经合组织完成了对《跨国公司和税务机关转让定价指南》(以下简称《转让定价指南》)的重大修订和更新工作,发布了新版的《转让定价指南》。

(1) 继续保证公平交易原则澄清了交易利润法的地位,修订后的第二章序言也再次声明没有哪种方法能

够适用于每种可能的情形,同样,我们也不必否定任何特定方法的适用性。

(2) 在讨论交易利润方法中介绍贝里比率(Berry Ratio),以及在可比性方面进一步的指导。2010指

南增加了第三章A.4的部分,扩充了几页关于在实施可比性分析的过程中如何处理可比非受控交易的方法和重要性的论述。这一补充为纳税人和政府提供了更多关于以下几个方面的有用性和局限性方面的指导:对内和对外可比性,国内、国外和非公开可比性的来源(例如数据库)和适用性。2010准则包含了一个关于营运资金调整的附录,目的是指导纳税人在进行调整的过程中提高可比性。该附录提供了关于营运资金调整的有用的背景介绍,包括为什么营运资金的调整可以提高可比性,计算营运资金调整的过程,以及一个计算运营资金调整的实例。

(3) 关于转让定价方法的新指导(一部分缺乏指导);

(4) 在对可比非受控交易实施可比性分析的时候使用的九步“典型过程”;

(5) 关于业务重组的考虑实际上能够影响所有关于转让定价的讨论。

第二篇:经合组织转移定价指南20xx版

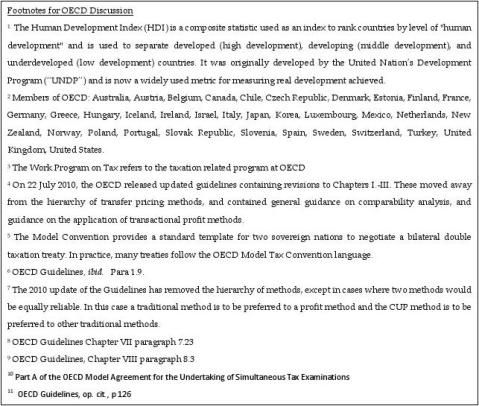

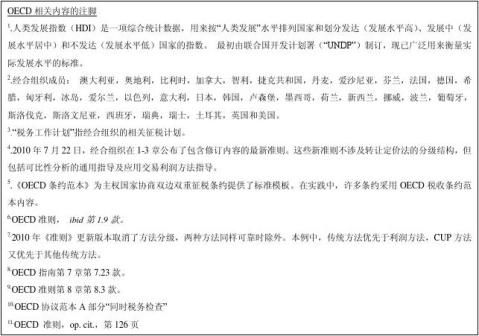

OECD章程

现行OECD准则包含的内容可分成以下章节:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

总体而言,第一章笼统介绍公允原则的属性、应用指导和可比性分析的重要性。第二章规定可用来测试受控交易公允原则的转让定价方法。第三章详细介绍执行可比性分析,可比对象的选择,可比性的调整和公允原则的范围。第四章介绍处罚、调整和避免双重征税和其他问题的步骤。第五章介绍纳税人在设定转让价格时应当考虑的信息类型,纳税人在税务机关要求下应当保留和制订的文件。第六章到第八章介绍在对待无形资产时需考虑的特殊事项,按照公允原则在申请框架制订集团内部服务和出资协议。

第九章介绍20xx年准则包括业务重组的转让定价。本章将介绍风险分担是否符合公允原则,风险分担产生的影响,公允原则对重组本身的补偿作用,例如有形和无形资产的转让,重组之后的交易报酬,交易可能被税务机关忽视或重新定性的情况。

除OECD准则外,辅助转让定价工作的其他重要OECD文件包括:OECD税收协定范本(“OECD范本”)5,及其相关评论和报告,例如第7条和第9条的应用评论和“常设机构利润归因”报告。 OECD还公布了有关准则和转让定价领域不同方面的结论报告。

独立交易原则

准则第一章B部分支持公允原则,指导纳税人如何确保其受控交易符合该标准。前提是要接受审查的转让价格,必须与非关联方在可比情况下参与相同交易可能承担的定价一致。准则认为,如果受控和非受控交易的“经济相关特征”具有可比性,那么非受控交易的结果可以作为有用的参考基准。最后,本节指出由非受控交易产生的系列价格或利润可以用来演示对公允原则的遵从情况。

依照基本原理,准则指明公允原则能在很大程度上保证税收处理的公平性。由于公允原则使关联企业和独立企业处于更平等的税收基础,从而避免税务上的优势或劣势导致这两种实体的相对竞争地位发生变化。制订经济决策无需考虑这些税务内容,有利于促进国际贸易和投资增长。准则表明事实证明公允原则在绝大多数情况下都能有效发挥作用,但同时也承认由于某些领域的情况过于复杂因而无法采用该公允原则,例如高度专业化的产品进行集成生产,和/或提供专业化服务时。6

公允原则 转让定价方法 可比性分析 避免和解决转让定价冲突的行政方法 资料 无形资产的特别注意事项 集团内部事务的特别注意事项 出资协议 业务重组的转让定价

转让定价方法

准则第二章第二部分简要介绍了三种传统交易方法--可比受控价格法(“CUP”)、转售价格法(“RP”)和成本加成法(“CP”)。第二章第三部分介绍了交易利润方法--交易净利润法(“TNMM”),利润分割法(“PS”),包括对后一种方法的不同分析方式(如出资分析或残差分析)的介绍。

原经合组织19xx年的报告反映出对19xx年美国法规的一些思考。 但是它描述了符合公平定价的这三种标准方法是如何形成的:可比受控价格法(“CUP”)、转售价格法(“RP”)和成本加成法(“CP”)。 它假设上面三种标准方法不实际,简要讨论了使用其他基础来评估利润是否符合公平标准所存在的问题。 但19xx年的报告对这些方法的应用并未定下严格的优先顺序;实际上,它表示在特定情况下很可能使用不止一种方法。19xx年的报告拒绝采用“全球性”方法,按因素(如营业额、资产和费用等)成比例分配全球利润,它认为这种方式可能导致结论太过随意且不正确。

7OECD准则最初于19xx年发布时就表示明显倾向于 CUP方法的观点。 准则还考虑不得已

的情况下,可以采用PS和TNMM交易利润方法。准则表示传统的交易方法是建立关联企业实际采用公平运营的最直接方式,并且优于其他方法。但是,OECD准则当前最新版本已经修改了此观点,并重点说明选择转让定价方法时需要根据给定事实和特殊情况找出最合适的方法。选择转让定价方法时应考虑不同方法的优势和劣势,以及在可比性分析中对特殊情况的适应性、信息的可用性,以及受控和非受控交易的可比性程度。可能需要考虑是否可以根据受控和非受控交易之间的差异进行可靠的调整。例如,由于缺少合适的可比数据,可能不能使用传统方法。但可以对这些可比对象进行调整,以允许受控和非受控交易之间在条件上的差异。

现在准则强调,没有一种特殊方法在所有情况下都是最适合的。它们还指出,对于不适合这些情况的方法,没必要予以证明。如果使用的转让定价方法合适,不必通过证明其他方法不能用来显示它是“最佳方法”。

但准则仍然表示,在特定情况下,传统交易方法及利润方法可以在同等可靠的方式下使用时,应优先选择传统方法,因为传统方法是在基于公允原则的关联方之间建立商用和金融关系的最直接方式。但准则也承认在某些情况下,例如是双方都有特殊重大贡献(如独特的无形资产或服务)的交易,PS方法可能才是最可靠的方法。

基本信息是应当使用最合适的方法,不应排除相关的证据。有些制订了国内法规的经合组织成员国试图确立一个大致顺序或优先级,不过这类国内法规在引入所有相关证据方面具备足够的灵活性。当然,如果不要求选择“最佳方法”,征税体系可能会给纳税人造成一些额外的行政负担。这些体系规定要通过举证责任来证明为什么已选的方法最合适而其他未选的方法就不合适,而这样会给纳税人增加遵从法规要求所造成的成本。

需要特别考虑的领域

对于一般法规和方法尚不完善的特定领域,准则在实际应用中遇到了挑战。准则生效实施一段时间后,这些新的挑战会列入经合组织议程。这些新挑战涉及到公允原则在无形资产交易、

集团内部服务和跨国集团出资协议(“CCA”)中的应用。

无形资产

准则特别关注涉及无形资产的的交易,因为这些交易通常在税收中难以评估。无形资产包括专利、商标、商标名称、设计或型号、技术、肖像、文学艺术知识产权、专业技术和商业机密的使用。准则承认资产的实际价值和/或风险可能在公司账目中无法得到准确评估。它全面描述了哪些情况可能构成无形资产交易和营销,重点阐述相关的无形资产带来的实际经济影响,而非创建资产所需的财政支出或分配的会计价值。

准则列举了无形资产的不同形式,并确认在涉及无形资产的受控交易中应用公允原则具有一定难度。 这类资产通常具有一些特殊特征,致使难以在交易时确定其价值。一般来说,无形资产可以授权给关联方使用,或者在某些情况下可以彻底出售给关联方。 在确定交易的公平性质时,必须考虑在类似情况下独立方会怎么做。

在这些情况下,制订公平定价时必须同时从许可人和被许可人(在授权许可中),或转让人和受让人(在无形资产的转让中)角度考虑。因此,对于许可人/转让人而言,公平价格是可比独立企业愿意授权或转让该资产的价格;而从被许可人/受让人角度而言,在考虑独特的业务运营和其他相关环境后,一家可比独立企业却可能不愿支付这样一个价格。

无形资产的价值以及无形资产对所得收入所起的作用可能十分难以确立。 例如,注册商标或品牌名对未来盈利所起的作用难以确定。 对无形资产的评估可能涉及对无形资产未来收入流的评估,而在特定交易时所做的评估可能与最终产生的收入不一致。

OECD 准则现在建议,在这些情况下对无形资产进行评估可以按类似情况下独立方协商的安排执行。 如果最初无形资产的未来收入流难以确定,独立方在使用无形资产时只需要制订很短的合同,或者他们可以在合同中加入价格调整条款。依照这样的价格调整条款,支付的使用费率可能随销售量的增加而提高。

准则规定了确认无形资产转让协定和基于公允原则计算的相关规则。准则还提供交易时难以确定无形资产价值,以及由不拥有该无形资产的关联公司开展营销等特殊情况下计算公平定价的指导。 无形资产的一个常见问题就是难以确定它们的自身价值,在某些情况下(例如市场营销的无形资产)甚至难以确认它们的存在。 经合组织目前正在与关联方就无形资产的转让价格进行协商,其中一个重要问题就是转让定价中对无形资产的定义。 针对准则,可能最好明确哪些无形资产可以进行转让定价调整。 转让定价显然需要考虑专利和注册商标这些无形资产,但有关其他类型的无形资产的立场却没这样明确。例如,公司“第一推动因素”的优势,卓越的管理技能,进入特定活动存在的壁垒,“人员到位”的优势,规模或未来盈利潜力带来的优势等,在某些情况下这些都被视为无形资产。 经合组织正在研究以后是否需要对转让定价中涉及的这些资产处理进一步加以明确。

经合组织就无形资产开展的协商也可能对转让定价中的商誉处理进一步加以明确,因为这已经成为引发了不同观点的一个问题。 另一种可能的发展趋势是修改准则,以便提供评估无形资产金融方法的更多指导。

集团内部服务

就集团内部服务而言,准则指出跨国集团通常会安排大量服务供集团成员使用,如行政、技术、金融和商业服务等。准则还明确指出这些服务可能包括集团管理、协调和控制职能,它们可能由专门指定的集团成员(如集团服务中心)或者另一个集团成员提供。主要问题是(a)集团内部服务实际上已经提供;(b)出于税收目的对该服务进行的集团内部收费应基于公允原则。测试的关键是处于可比环境的独立企业是否愿意为该服务付费;如果愿意,独立企业愿意付多少。特定交易的事实和实际情况是确定是否已经提供服务,款项是否应当支付的指导原则。

准则举例说明如何确定集团内部服务是否已经提供,该服务是否采取了公平收费。准则还解释了母公司提供给附属公司的“股东活动”服务与出于附属公司盈利目的的其他商业活动之间的差别,包括计算公平款项的指导及部分集团内部服务实例。

鉴于直接结算和收取某些公司间服务费用具有一定难度,准则指出采用间接收费方式对跨国公司来说通常更实际可行。这涉及到确认提供服务的成本,这些成本形成“成本池”并且将来在接受服务的集团公司之间进行分摊。在不同服务接受者之间分摊成本,需要采用合适的分配要诀或一套分配要诀,适当时候对成本加价。

这种间接收费方式“应当是被允许的,但前提充分考虑了向接受者提供的服务价值,以及在独立企业间提供的可比服务的范围。”8当公司提供的服务是向第三方(除其他集团公司外)提供的主要业务活动的一部分,间接收费方法将不适用。

使用间接收费方法的一个前提条件是,在集团公司之间分配服务时使用的分配要诀必须合理,同时需充分考虑服务类型和提供服务的环境。成本基数应依照有效的会计原则计算,防止有人进行操纵。在集团公司之间实行的费用分摊应与使用该服务的各个公司享受的利益有关。

出资协议

准则将 CCA 定义为“企业之间就开发、生产或获得资产、服务或权利而进行的成本和风险分摊,以及确定各方参与者在那些资产、服务或权利中获得的利益的性质和程度而达成的”框架。9 CCA是一种合同框架,依照该框架,各方参与者在总出资中所占的份额比例应与参与者在预期总收益中所占的份额比例一致。CCA的每位参与者有权作为合法的所有者(而不是受让人)单独使用其在CCA中的利益,而不必支付特许权使用费或其他费用。CCA在无形资产的研发中最常见,但也可以用于其他目的,例如其他联合筹资或成本分配和风险分担;或用于开发或购置财产等。使用CCA的另一个领域是获取服务,例如集中支持和管理服务、共同广告活动时。

准则规定了确定 CCA作用时采用公允原则的一套通用法则,包括对双方利益的一般预期,这是真正实现CCA的基础。换句话说,一个独立的无关联的公司应当能够从这类协议中获得与出资相符的利益。 准则还规定了确定参与者及测量每位参与者出资额的相关指导。准则然后介绍了如何确定该分摊是否合适,如何进行出资和平衡收支的税务处理。

准则规定,如果参与者在CCA总出资中的份额比例(根据任何收支平衡调整)与参与者依照CCA预期获得的总收益的份额比例不一致,可以由税务管理机关调整参与者的出资。如果事实与情况表明协议的实际情况与达成的条款不一致,税务管理机关可以忽视CCA的部分或全部条款。最后,准则规定了CCA建项、撤销或终止的附加指导,以及构建CCA和CCA建档的相关建议。

负责运营CCA的公司需要对运营CCA的管理服务收取适当费用,因此CCA管理相关成本应与协议中发生的成本加以区分。需要通过详细的协议对CCA加以证明,协议内容应确切规定哪些活动属于CCA。这些活动可以按成本付费,不属于CCA的活动则必须按公允原则提供报酬。此外需要定期提供按比例出资和预期收益的分析。

金融服务

准则参见了“常设机构的利润归属报告”第三部分C“关于财务工具的全球贸易中,使用PS方法分析转让定价”的有关讨论。 在集成度的运营中,PS方法可能是最合适的转让定价方法。

业务重组

准则第九章与业务重组的转让定价有关。包括重组中各方的风险分担,与重组有关的赔偿支付,重组后协议采用公允原则,以及税务管理机关未认可的交易或新业务结构。

风险分担应根据各方之间的合同条款执行,只有涉及经济实质时才需要税务管理机关插手。因此,有必要审查合同条款是否按公平原则分担风险,各方在实践中是否遵守了合同条款。然后,必须考虑该风险是否具有经济意义,它们会导致什么转让定价后果。税务机关需要确定风险分担是否是独立各方在类似情况下早应商定的一个问题。这包括各方如何控制风险的考虑事项。

准则还规定了重组实体由于在重组中承担了转让的职能、资产和风险,应当获得多少公平赔偿;或因为集团内部的原协议发生终止或重新谈判时应获得多少赔偿。这涉及到集团结构变动对各方职能分析产生了多大影响。同时还取决于重组的商业原因和预期收益,以及原本应提供给独立方的选项。

准则阐明了潜在盈亏的再分配,这种再分配针对的不是资产自身,而是由权利或其他资产带来的潜力。问题是已经转让的权利或资产是否是按公允原则赔偿的。

重组后的实体是否有权因重组带来的不利影响获得赔偿,这取决于原来的集团结构和协议是否已通过书面形式加以确认,是否制定了有关赔偿的条款,以及可以向重组方提供什么选项。例如,重组后一方承担的风险和获得的潜在利润都比原来低,税务管理机关可以询问独立方

是否愿意接受该协议;如果愿意,需要做什么样的赔偿。

准则强调,与一开始采用类似方式制订的协议相比,应用于重组后协议的公允原则不应有差别。要确定重组后的地位,经合组织建议对重组前和重组后的地位分别做一份可比性报告,并且为重组中涉及的交易提供充分的文档记录。

值得注意的是,如果重组后的实体与接管其职能、资产和风险的公司会建立长久的商业关系,就不能把重组所做的赔偿和重组后的薪酬安排孤立看待。同时,对重组前和重组后的利润水平所做的比较,可能与对重组和推动各方之间利润分配变化的价值驱动因素的理解有关。因为重组获得的利益,例如因地理位置节约的成本,可能需要按照公允原则在各方之间分配,这时需考虑独立方在类似情况下可能会怎么做。

经合组织支出,税务管理机关未认可的交易应当属于例外而不是常规,准则中对此应当已经加以明确。准则建议公允原则通常应当在转让定价调整时使用,而不是在纳税人参与的交易未认可或需重新定性时使用。如果考虑案例事实和情况后能找到合适的转让价格,“独立方之间找不到特定交易”这一事实本身并不意味着必须重新定性。

有关交易重新定性的可能性,准则第1.37款指这种情况:“从总体来看,与交易有关的协定,不同于独立企业通过商业上合理方式采用的协议,并且实际结构在实践中会妨碍税务管理机关确定合适的转让价格。” 准则未进一步指导如何确定采用“商业上合理方式”的独立方应做什么,商业重组章节建议制订未采用商业合理方式的受控交易的相关决策时必须审慎,而且这些决策不能导致交易重新定性。

经合组织明确表示,在有其他选项的情况下,独立方不能参与明显会带来不利结果的交易。相关全部交易必须一起检查,以确定重组条款是否对所有参与方都具有商业意义。重要的是,准则阐明了提供的职能、资产和风险实际上已经转让,为了达到节税目的可以用商业上合理的方式重组。OECD准则强调进行业务重组可能有集团级的合法原因,但由于每个实体都采用公允原则,只需找出各个实体在重组中所涉交易的正确转让定价即可。

资料

准则专门用整章内容阐述资料主题。准则指出,纳税人应按公允原则对受控交易定价,并且应当记录他们在税务机关审计或调查时参与的工作。准则强调,纳税人是否提供资料,在一定程度上取决于国内税收法规定谁承担举证责任。但准则总结即使举证责任由税务管理机关承担,纳税人可能仍须提供足够的资料,以便对纳税人的转让价格进行检查。具体地讲,调查单个转让定价的相关信息视本案“事实和情况”而定。出于这个原因,几乎不能用任何广义方法定义纳税人调查时应提供的信息的确切范围和性质。

准则建议下列信息通常应包括在内:

-

-

- 受控交易的相关信息,例如交易条款、交易有关的经济条件、转让财产的详细信息; 交易涉及的每个实体的信息,包括业务概况、组织结构和基本财务信息; 定价信息,包括业务战略和特殊环境,例如影响定价和策略制订的因素等;

-

-

-

与交易及涉及交易的每位纳税人有关的一般商业和行业状况; 与接受审查的交易相关的信息,如执行的职能、承担的风险和持有的无形资产; 财务信息,包括制造/分销成本和一般及行政开支报告;

准则明确指出,资料要求不应给纳税人造成与情况不相称的费用和负担。此外,它建议纳税人无须出示不属于他们实际所有、控制或不能以其他合理方式提供的资料(例如对于纳税人竞争对手保密的信息)。 准则承认要公司提供外商关联企业的资料(对定价检查至关重要)可能有一定难度。

转让定价管理

准则就税务管理问题的讨论主要集中在成员国行政机构的合作上。每个成员国根据自己的立法和行政程序和实际做法制订国内法规遵从法则。准则承认,由于关系到国家主权和不同税收制度的原因,应由各国单独决定税务法规遵从惯例。不过准则指出,应用的公允原则要求采用明确的立法程序确保对纳税人提供充分保护。准则还建议,税收收入不能转移到程序规则过于苛刻的国家。准则进一步明确,开展跨国转让定价调查时,转让价格有可能在一个税务辖区被接受,而在其他税务管辖区不被接受。在特定情况下,跨国集团可能面临双重征税。如果遇到这种情况,准则建议税务管理机关应起注意在不同税务管辖区之间实行税务公平分配,以避免对纳税人进行双重征税。

在当前情况下,准则重点介绍了税收征管的四大领域:法规遵从惯例、相应的调整和双方协商程序,同时税务检查,安全港规则,与APA和仲裁相关的建议。

在法规遵从惯例领域,准则提供了调查(即转让定价审计),举证责任和处罚的相关指导。对于审计,准则建议不必采用高精度方法;同时鼓励税务检查人员应用公允原则时需考虑对纳税人的商业判断。 准则指出经合组织成员国之间在举证责任方面的分歧可能会带来严重的问题。准则参考OECD范本注释,阐明各国应如何解决该问题。至于处罚,准则对此未做出整体建议,因为处罚属于更广泛范畴的税务法规遵从程序的一部分。它阐明处罚的主要目的是防止法规不遵从,经合组织成员不应对具有遵守法规良好意愿的纳税人采用严厉处罚。

不同税务管理机关在转让定价领域的相互作用,详见双方协商程序和相应的调整部分。分析内容包括OECD范本第9-25条,包括解决方案的程序和指导,如仲裁的可能性。它同时提供了相应的时间限制、双方协商诉讼的建议时间,以及纳税人在该过程参与的活动以及相应程序的公开。同时还讨论了征税不足、应计利息和二次调整的挑战等问题。

同时税务检查的定义是“两方或多方在各自领土上,同时独立检查纳税人税务,以及在此期间它们可以交换各自拥有的信息来实现共同或相关利益的一种协议。”10准则规定了同时税务检查的法律基础(OECD范本第26条)及使用程序的建议。

安全港概念参见相关国家的一般税法解释。因此,安全港是一种适合给定类别的纳税人的法定条文。它通过代之以例外,免去税法关于具备纳税资格的纳税人在转让定价中的义务,通

常是比较简单的义务。在转让定价环境中,免除的程度可能不一样,从全部免除目标纳税人义务到更有限的免除均包括,不过具备免除资格的前提是必须符合相关程序规则。经合组织准则讨论了支持安全港使用的因素,以及使用它们对纳税人和税务管理机关有什么好处。同时它还回顾了使用安全港时遇到的潜在问题,包括未遵从公允原则的潜在可能,双重征税的风险以及双方协商程序的难点。

条约方面

税务条约是各国政府处理跨境税务问题和处理相同收入的征税权分配的主要工具。因此,税务条约对转让定价处理具有影响,因为在一些国家的应纳税收入数额是参考公允原则确定的。OECD范本第9条(关联企业)指出,“如果对两个相关企业对其商业或财务关系(与独立企业之间的关系不同)的制订或实施设置了条件,由于这些条件的存在,本来可以计入其中某个企业的任何利润因为该限制而未计入的,可以包括在该企业的利润中征税。” 换句话说,如果关联企业之间的关系性质影响到任何一方应得的利润水平,有权对这些利润征税的政府机关可以参考独立交易原则调整利润,并对附加利润收税。 准则的当前版本引用第9条作为当局机关参考的公允原则。

OECD范本还规定了处理转让定价事件特殊重要性的其他内容:

- 第5条定义了常设机构;

- 第7条(业务利润条款)规定了将应纳税利润分配给某分支机构或其他常设机构时使用

公允原则的相关限制;

- 第11(6)条和12(4)条规定了减免税收利息和特许权使用费(这是付款人和收款人

存在一种特殊关系)的相关限制;

- 第23条规定要避免双重征税;

- 第25条规定如果主管机关就一个或多个问题未达成一致意见时,条约合作伙伴和仲裁

程序的主管机关之间应采取双方协商程序;

- 第26条规定了那些主管机关之间可以交换纳税人信息;

但一般情况下,只有少量条约包含OECD范本第9(2)条“相应调整”后的相关内容。

准则在某条款中对双方协商程序的优势进行了评论,其内容与OECD范本第25(5)款类似。如果无仲裁相关规定,主管机关可以努力达成一致意见;如果它们最后未达成协议,目前尚无机制来解决这一问题。条约中包含仲裁内容的,可以通过仲裁方式解决问题。根据第25

(5)款规定,如果主管机关不能就一个或多个问题达成协议,可以将这些问题提交仲裁,这种方式可以使双方协商程序变得更有效。 仲裁程序为解决问题提供更多可能性,纳税人因此可以更频繁地使用双方协商程序,即使最终可能不需要仲裁。 政府部门也愿意更有效地执行双方协商程序,以便无需仲裁就能解决问题。

预约定价协议

预约定价协议(“APA”)是“在受控交易之前确立一套合适的规范(例如方法,可比对象和适当调整,对未来事件的关键假设),用来确定那些交易在一定时段内的转让定价”。11准则规定了监管APA的法律和行政规则,及确定这类协议可能存在的风险和优势的方法。经合组织发现,具有APA经验的成员国对此普遍持赞成态度;准则对建立有效APA程序提出了

建议。这些建议包括在可能的情况下制订双边或多边APA协议,保证所有纳税人能公平加入APA,以及制订主管机关和改进程序之间的工作协议等。

就APA范围而言,准则指出准备APA时务必要注意所做的预测准确可靠。预测是否可靠,则与这些关键假设的基础有关。关键假设应考虑条件的潜在变化,例如相关企业执行的职能,或利率等外部条件的变化。预测是否可靠取决于特定的环境,确定APA的范围时必须将这点考虑进去。通常,预测转让定价方法及方法的应用是否合理,往往比预测未来盈利水平或价格更可靠。

准则建议,如果可能的话,APA应是根据相关税收条约的双边协商程序建立的双边或多边关系。如果纳税人感到难以达成协议或接受公允原则协议,此时选择双边APA比单边APA更合适,因为它可以避免税务机关进行费用高昂的问询甚至处罚。在有些税务管理中,可能无法达成单边APA协议,因为国内尚无立法允许与纳税人签订有约束力的协议。

准则指出,虽然在实际操作中APA可能只适合纳税大户,但需要说明的是纳税人应享有平等待遇。 税务管理机关应让规模较小的纳税人也有机会加入APA以分配到资源,并且应考虑使用可以缩减成本的简单加入。税务管理机关就APA应用制订的询问级别应与纳税人所参与的国际交易数量相当。

准则还建议税务管理机关之间应就承担APA任务签订工作协议,包括纳税人就转让定价问题要求签订APA达成的双方协商的指南。准则也在条约伙伴国之间应用双边APA的结论。相同信息还应同时提交给税务管理机关,各机关之间协定的方法应符合公允原则。

OECD Regulation

The guidance contained in the current OECD Guidelines is divided into the following chapters:

?

?

?

?

?

?

?

?

? The Arm's-Length Principle Transfer Pricing Methods Comparability Analysis Administrative Approach to Avoiding and Resolving Transfer Pricing Disputes Documentation Special Considerations for Intangible Property Special Considerations for Intra-Group Services Cost Contribution Arrangements Transfer Pricing Aspects of Business Restructurings

In general, Chapter One broadly covers the nature of the arm’s length principle, guidance for its application and the importance of a comparability analysis. Chapter Two covers the transfer pricing methodologies that can be employed to test the arm's length character of controlled transactions. Chapter Three goes into detail about performing a comparability analysis, selection of comparables, comparability adjustments and the arm’s length range. Chapter Four covers penalties, adjustments and procedures to avoid double taxation and other issues. Chapter Five deals with the types of information a taxpayer should be expected to consider when setting transfer prices and the documentation a taxpayer should be expected to maintain and produce upon a request by a tax authority. Chapters Six to Eight cover the particular considerations that need to be taken into account when looking at intangibles, intra-group services and cost contribution arrangements within the framework of the application of the arm’s length principle.

Chapter Nine on the transfer pricing aspects of business restructurings was included in the Guidelines in 2010. The chapter looks at the issue of whether the allocation of risk is at arm’s length and the effects of this risk allocation, the arm’s length compensation for the restructuring itself, such as the transfer of tangible and intangible assets, the remuneration of the transactions after the restructuring, and the circumstances in which the transactions might be disregarded or re-characterized by the tax authorities.

In addition to the OECD Guidelines, the other key OECD documents that assist in transfer pricing work are OECD Model Tax Convention (“OECD Model”)5, and its related commentary and reports, e.g. the commentary on the application of Articles 7 and 9 and the report on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments. The OECD also publishes reports on consultations of various aspects of the Guidelines and transfer pricing related areas.

Arm’s Length Principle

Chapter One Part B of the Guidelines endorses the arm's length principle and provides guidance on how taxpayers can ensure that their controlled transactions meet this standard. The premise is that the transfer pricing under review must be consistent with the pricing that would have been undertaken if unrelated parties had engaged in the same transaction under comparable circumstances. The Guidelines hold that the results of uncontrolled transactions can serve as a useful benchmark only if the "economically relevant characteristics" of the controlled and uncontrolled transactions are comparable. Finally, this section specifies that a range of prices or profits developed from uncontrolled transactions can be used to demonstrate compliance with the arm's length standard.

By way of rationale, the Guidelines state that the arm's length principle provides broad parity of tax treatment. As the arm's length principle puts associated and independent enterprises on a more equal footing for tax purposes, it avoids the creation of tax advantages or disadvantages that would otherwise distort the relative competitive positions of either type of entity. Removing these tax considerations from economic decisions promotes the growth of international trade and investment. The Guidelines state that the arm's length principle has been found to work effectively in the vast majority of cases, but recognizes that there are some areas where it is difficult and complicated to apply, e.g. for groups dealing in the integrated production of highly specialized goods, in unique intangibles, and/or in the provision of specialized services.6 Transfer Pricing Methods

Part 2 of Chapter 2 of the Guidelines outlines the three traditional transactional methods – the comparable uncontrolled price (“CUP”) method, the resale price (“RP”) method and the cost plus (“CP”) method. Part 3 of Chapter 2 looks at the transactional profit methods – the transactional net margin method (“TNMM”) and the transactional profit split (“PS”) method, including the different approaches to the latter method such as a contribution analysis or a residual analysis. The original OECD 1979 Report reflected some of the thinking on the 1968 United States regulations. However, it described what have become the three standard methods of arriving at an arm's length price: the CUP method, the RP or resale minus method, and the CP method. It briefly discussed the issues in using other bases for estimating the profits at an arm's length standard if one or other of the three standard methods was not practical. The 1979 Report, however, laid down no strict order of priority for application of any of the methods; indeed it said that it was quite possible more than one method could be used in a particular situation. The 1979 Report refused to endorse "global" methods of allocating worldwide profits in proportion to factors such as turnover, assets, costs, etc., saying such methods could result in an arbitrary and incorrect conclusion.

The OECD Guidelines issued in 1995 initially expressed a clear preference for the CUP method.7 The Guidelines also considered the transactional profit methods – the PS method and the TNMM – to be methods of last resort. The Guidelines stated that traditional transaction methods were the most direct means of establishing whether associated enterprises are actually operating at

arm's length, and were preferable to other methods. However, the current updated version of the OECD Guidelines has modified this view and emphasizes that the selection of a transfer pricing method involves finding the most appropriate method given the facts and circumstances of the particular case. Selection of a transfer pricing method should take into account the strengths and weaknesses of the various methods and their suitability in the particular situation in the light of the comparability analysis, the availability of information and the extent to which the controlled and uncontrolled transactions are comparable. It may be necessary to consider if it is possible to make reliable adjustments to adjust for differences between the controlled and uncontrolled transactions. For example, it may appear that a traditional method cannot be used because of a lack of suitable comparable data. It may, however, be possible to make adjustments to those comparables to allow for the differences in conditions between the controlled and uncontrolled transactions.

The Guidelines now emphasize that no particular method will be the most suitable in all situations. They also state that it is not necessary to demonstrate that methods that were not used were unsuitable in those circumstances. If the transfer pricing method used is appropriate, it is not necessary to show that it is the “best method” by demonstrating why other methods were not used.

The Guidelines still state however that where a traditional transactional method and a profit method may be used in an equally reliable way in a particular case, the traditional method should be preferred, because the traditional methods are the most direct way of establishing that commercial and financial arrangements between related parties are at arm’s length. However, the Guidelines also acknowledge that in some situations, such as transactions where both parties make valuable and unique contributions (e.g. unique intangibles or services), a PS method may be the most reliable.

The basic message is that the most appropriate evidence should be used and that no relevant evidence should be excluded. While some OECD member countries with domestic rules have tried to set a rough order or priority, there is enough flexibility in such domestic rules for all relevant evidence to be introduced. There are, of course, some added administrative burdens on taxpayers in taxation systems where there is a requirement to choose the “best method”. These systems impose the burden of proof to demonstrate why the method chosen was most appropriate and why other methods not chosen were inappropriate and this adds to compliance costs for the taxpayer.

Special Areas for Consideration

The Guidelines, in their practical application, have been faced with challenges in specific areas where the general rules and methods have proved to be incomplete. Over the time period during which they have been in effect, these new challenges have been added to the OECD's agenda. These challenges relate to the application of the arm's length principle to transactions involving intangible property, intra-group services and cost contribution arrangements (“CCAs”) within a multinational group.

Intangible Assets

The Guidelines pay particular attention to transactions involving intangible assets because these transactions are often difficult to evaluate for tax purposes. Intangible assets include the right to use patents, trademarks, trade names, designs or models, technology, likeness, literary and artistic property rights, know-how, and trade secrets. The Guidelines recognize that the true value, and/or the risks related to the assets may not be accurately valued in company accounts. A comprehensive description of what may constitute trade and marketing intangibles is provided with a strong emphasis on looking at the true economic impact of the intangible in question and not the financial outlay to create it or the accounting value assigned.

The Guidelines provide examples of different forms of intangible assets and recognize that applying the arm's length principle may be difficult for controlled transactions involving intangible assets. Such property will often have special characteristics that make the value difficult to determine at the time of the transaction. Generally, an intangible asset may be licensed for use by a related party or it may in some cases be sold outright to the related party. In determining the arm’s length nature of the transactions it is necessary to consider what independent parties would have done in similar circumstances.

Arm's length pricing in such cases must take into account the perspective of both the licensor and the licensee (in a licensing arrangement) or the transferor and the transferee (in a transfer of intangible property). Thus, for the licensor/transferor, the arm's length price is the price for which a comparable independent enterprise would be willing to license or transfer the property, while from a licensee/transferee perspective, a comparable independent enterprise may not be prepared to pay that price, given its unique business operations and other relevant circumstances.

The value of an intangible and the contribution that an intangible asset makes to the income earned may be very difficult to establish. For example, the contribution of a trademark or brand name to future earnings is difficult to establish with any accuracy. Valuation of an intangible may involve estimating future income flows relating to the intangible, and the estimates made at the time of a particular transaction may not correspond to the income that eventually arises. The OECD Guidelines currently suggest that the valuation of an intangible asset in these circumstances might follow the arrangement that would have been made by independent parties in similar circumstances. Where the future income stream from an intangible asset is very uncertain at the outset, independent parties might only be prepared to make very short contracts for the use of that intangible asset, or they might incorporate price adjustment clauses in their contract. Under such a price adjustment clause, the royalty rate paid might become higher as sales increase.

The Guidelines, therefore, provide rules for identifying arrangements made for the transfer of intangible property and calculation of an arm's length consideration. The Guidelines also provide guidance on calculating arm's length pricing when the value of the intangible is highly uncertain at the time of the transaction and in special situations where marketing activities are undertaken by associated companies which do not own the intangible.

One common problem with intangible assets is that it is more difficult to know their value or

even in some cases (such as with certain marketing intangibles) be aware that they exist. The OECD is currently consulting with relevant parties on the transfer pricing aspects of intangibles and one important issue is the definition of an intangible asset for the purposes of transfer pricing. It might be preferable for the Guidelines to clarify precisely which intangible assets should be the subject of transfer pricing adjustments. Although it is clear that and intangible such as patents and trademarks are assets that need to be taken into consideration for transfer pricing purposes, the position is less clear in respect of other types of intangibles. For example, the “first mover” advantage of a company, superior management skills, the existence of barriers to entry in a particular activity, the advantage of having a “workforce in place”, or the advantages resulting from scale or future profit potential could all be regarded as intangible assets in some circumstances. The OECD is examining the question of whether further clarification might be needed for the treatment of these assets for transfer pricing purposes.

The OECD consultation on intangibles may also result in further clarification of the treatment of goodwill in a transfer pricing context, as this is an issue that currently gives rise to differing views. Another possible development is that the Guidelines could be amended to provide more guidance on financial methods of valuing intangibles.

Intra-group Services

With regard to intra-group services, the Guidelines recognize that multinational groups generally arrange for a wide scope of services to be available to group members, such as administrative, technical, financial and commercial services. The Guidelines also recognize that such services may include group management, coordination and control functions and may be provided by a specially designated group member (e.g. a group service center), or by another group member. The main issues are (a) whether intra-group services have in fact been provided and (b) what the intra-group charge for such services for tax purposes should be on an arm’s length basis. The key tests are whether an independent enterprise in comparable circumstances would have been willing to pay for the service, and if so, what would independent enterprises be willing to pay. The actual facts and circumstances of particular transactions are the guiding principle of determining whether a service was rendered and if consideration is payable.

The Guidelines offer some illustrative examples for determining whether intra-group services have been rendered and for determining an appropriate arm’s length charge for such services. The distinction between “shareholder activity” services provided to a subsidiary from a parent and other business services provided for the benefit of the subsidiary is explained in the Guidelines, and they include guidance on calculating the arm’s length consideration and some examples of actual intra-group services provided.

In view of the difficulties of directly computing and charging certain intercompany services, the Guidelines acknowledge that it will often be a practical necessity for multinational groups to adopt an indirect charge method. This involves identifying the costs of providing the services, and these costs make up the “cost pool” to be allocated among the group companies receiving the services. An appropriate allocation key, or set of allocation keys, is then used to allocate the costs of the services between the various recipients of the services, applying a mark-up to the costs as appropriate.

Such indirect charge methods “should be allowable provided sufficient regard has been given to the value of the services to recipients and the extent to which comparable services are provided between independent enterprises”8. Where a company is providing services as part of its main business activity to third parties in addition to other group companies, the indirect charging basis would not be appropriate.

A condition of using an indirect charging method would be that the allocation key used to allocate services among group companies is reasonable, considering the type of service and the circumstances of its provision. The cost base should be computed under sound accounting principles, with safeguards against manipulation. The allocation of charges among group companies should bear some relation to the benefit received by each company that uses the services.

Cost Contribution Arrangements

The Guidelines define a CCA as a framework “agreed among business enterprises to share the costs and risks of developing, producing or obtaining assets, services, or rights, and to determine the nature and extent of the interests of each participant in those assets, services, or rights.”9 A CCA is thus a contractual vehicle in which each participant’s proportionate share of the total contributions should be consistent with the participant’s proportionate share of the overall expected benefits to be received. Each participant in a CCA is entitled to exploit its interest in the CCA separately as an effective owner thereof and not as a licensee, and so should not have to pay a royalty or other consideration. CCAs are most commonly seen for research and development of intangible property, but can be formed for other purposes, e.g. other joint funding or sharing of costs and risks, for developing or acquiring property, etc. Another area where a CCA may be appropriate is for obtaining services, such as centralized support and management services, common advertising campaigns, etc.

The Guidelines provide a general set of rules for applying the arm's length principle in determining CCA contributions, with the general expectation of mutual benefit being fundamental to a true CCA. In other words, an independent, unrelated company should be able to expect benefits from such arrangements that are consistent with its contributions. Guidance on determining participants and measuring the amount of each participant’s contribution is provided. The Guidelines then consider how to determine whether the allocation is appropriate and deal with the tax treatment of contributions and balancing payments.

The Guidelines state that where a participant’s proportionate share of the overall contributions to a CCA, adjusted for any balancing payments, is not consistent with the participant’s proportionate share of the overall expected benefits to be received under the CCA, a tax administration may adjust the participant’s contribution. If the facts and circumstances indicate that the reality of an arrangement differs from the terms agreed, a tax administration may disregard part or all of the terms of a CCA. Finally, the Guidelines provide some additional guidance on CCA entry, withdrawal, or termination and recommendations for structuring and documenting CCAs.

The company that is responsible for operating the CCA needs to charge an arm’s length fee for its administration services of operating the CCA, so costs relating to the administration of the CCA

need to be distinguished from costs arising within the arrangement. The CCA needs to be evidenced by a detailed agreement that specifies precisely which activities form a part of the CCA. These activities can be paid for at cost, while those that are not part of the CCA must be remunerated at arm’s length. Some analysis of proportional contributions and expected benefits will be required periodically.

Financial Services

The Guidelines refer to the discussion of the use of the PS method for analyzing transfer pricing in the case of the global trading of financial instruments in Part III Section C of the “Report on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments”. The PS method may be the most suitable transfer pricing method where there are highly integrated operations.

Business Restructurings

Chapter IX of the Guidelines is concerned with the transfer pricing aspects of business restructurings. This covers the allocation of risk between the parties to a restructuring, compensation paid in connection with the restructuring, application of the arm’s length principle to post-restructuring arrangements, and the circumstances in which the transactions or the new business structure may not be recognized by the tax administration.

The allocation of risk would be set out in the contractual terms between the parties, but this would be respected by the tax administration only if it has economic substance. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the question of whether the contractual terms provide for an arm’s length allocation of risk and whether the parties have conformed to the contractual terms in practice. It is then necessary to consider if the risks are economically significant and what are their transfer pricing consequences. Tax authorities will want to determine if the allocation of risk is one that would have been agreed between independent parties in similar circumstances. This includes consideration of which parties have control over the risk.

The Guidelines also look at the extent to which the restructured entities should receive arm’s length compensation for the functions, assets and risks transferred in the course of the restructuring, or an indemnification for the termination or renegotiation of the previous arrangements existing within the group. This involves an understanding of how the changes made to the group structure have affected the functional analysis between the parties. It also depends on the business reasons for and anticipated benefits from the restructuring, and the options that would have been available to independent parties.

The Guidelines look at the reallocation of profit/loss potential, which is not an asset in itself but a potential carried by rights or other assets. The question is whether there are rights or assets transferred that should be compensated at arm’s length.

The question of whether a restructured entity is entitled for indemnification for the detrimental effects of the restructuring may depend on whether the previous group structure and arrangements were formalized in writing, whether there was provision made for indemnification, and what options were realistically open to the restructured party. For example, a party may have

lower risk and lower potential profits after the restructuring, and the tax administration may ask if an independent party would have accepted such an arrangement, and if so what compensation would have been required.

The Guidelines stress that the arm’s length principle should not apply differently to post-restructuring arrangements as compared with arrangements that were structured in a similar way from the beginning. To determine the post-restructuring position, the OECD recommends that a comparability analysis should be performed for both the pre- and post-restructuring position, with the transactions involved in the restructuring being fully documented.

It is important to note that the compensation in respect of the restructuring and the post-restructuring remuneration arrangements cannot be looked at in isolation if the restructured entity will have an ongoing commercial relationship with the company that took over its functions, assets and risks. Also, comparisons of profit levels before and after the restructuring may be relevant to understanding the restructuring and the value drivers that account for changes in the allocation of profits between the parties. Benefits from the restructuring, such as location savings, may need to be allocated among the parties at arm’s length, taking into account the question of what independent parties would have done in similar circumstances.

The OECD points out that non-recognition of transactions by a tax administration should be the exception rather than the norm, as the Guidelines make clear. The Guidelines recommend that non-arm’s length behavior should normally be dealt with by means of an adjustment to the transfer pricing rather than non-recognition or re-characterization of the transactions entered into by the taxpayer. The mere fact that a particular transaction would not be found among independent parties does not in itself mean that re-characterization is necessary, provided that an appropriate transfer price can be found taking into account the real facts and circumstances of the case.

In relation to the possibility of re-characterization of transactions, Paragraph 1.37 of the Guidelines refers to a situation where “the arrangements made in relation to the transaction, viewed in their totality, differ from those which would have been adopted by independent enterprises behaving in a commercially rational manner and the actual structure practically impedes the tax administration from determining an appropriate transfer price”. The Guidelines do not give further guidance on how to determine what independent parties behaving in a “commercially rational manner” would have done and the chapter on business restructurings suggests that the decision that a controlled transaction is not commercially rational should be made only with great caution and should only rarely lead to a re-characterization.

The OECD makes it clear that an independent party would not enter into a transaction that is expected to be clearly detrimental to it if there are other options realistically available. The totality of transactions entered into must be examined together to determine whether the terms of the restructuring make commercial sense to all the parties. Importantly, the Guidelines clarify that provided functions, assets and risks are actually transferred, it can be commercially rational to restructure in order to achieve tax savings. The OECD Guidelines emphasize that there can be legitimate group-level reasons for business restructurings, but as the arm’s length principle looks at each entity separately it is also necessary to find the correct transfer pricing in relation to transactions involving each entity in the restructuring.

Documentation

The Guidelines devote an entire chapter to the subject of documentation. The Guidelines state that taxpayers should price controlled transactions in accordance with the arm's length principle and should document their efforts in the event of an audit or examination from a tax authority. The Guidelines stress that the documentation obligations of a taxpayer will depend, in part, upon where the burden of proof rests under domestic tax law. However, the Guidelines conclude that even where the burden of proof rests upon the tax administration, the taxpayer may be obligated to produce sufficient documentation to permit an examination of the taxpayer's transfer prices. Specifically, the information relevant to an individual transfer pricing inquiry depends on the "facts and circumstances" of the case. For this reason, is not possible to define in any generalized way the precise extent and nature of information that the taxpayer should reasonably be expected to produce at the time of the examination.

The Guidelines suggest that typically the following information should be produced:

? Information on the controlled transactions such as the terms of the transaction, the economic conditions surrounding the transaction and details on the property being transferred;

? Information on each entity involved in the transaction including an outline of the business, the structure of the organization and basic financial information;

? Information on pricing including business strategies and special circumstances at issue such as factors that influence the setting of prices or establishment of policies;

? General commercial and industry conditions surrounding the transaction and each taxpayer involved in the transaction;

? Information about functions performed, risks assumed and intangibles held in relation to the transactions under review; and

? Financial information including reports on manufacturing/distribution costs and general and administrative expenses.

The Guidelines clearly state that the documentation requirements should not impose on taxpayers any costs and burdens that are disproportionate to the circumstances. Further, it is recommended that taxpayers should not be required to produce documents that are not in their actual possession or control or otherwise reasonably available (e.g. information that is confidential to the taxpayer's competitor). The Guidelines recognize that a company may have problems supplying documentation regarding foreign associated enterprises essential to transfer pricing examinations.

Transfer Pricing Administration

Discussion on tax administration issues in the Guidelines mainly focus on cooperation between the administrative organizations of member states. Domestic compliance rules are developed in

each member country according to its own legislation and administrative procedures and practices. The Guidelines recognize that as a matter of national sovereignty and reasons of varying tax systems, tax compliance practices should be determined by individual countries. However, the Guidelines state that fair application of the arm's length principle requires clear procedural rules to ensure adequate protection of the taxpayer. The Guidelines also recommend that tax revenue is not shifted to countries with overly harsh procedural rules. The Guidelines further recognize that when cross-border transfer pricing investigations take place, a transfer price may be accepted in one jurisdiction but not accepted in the other tax jurisdictions. And in certain instances, the multinational group may be subject to double taxation. When issues such as these arise, the Guidelines recommend that tax administrations should be conscious of them and facilitate both the equitable allocation of taxes between jurisdictions and the prevention of double taxation for taxpayers.

In their current form, the Guidelines focus on four key areas for tax administration: compliance practices, corresponding adjustments and the mutual agreement procedure, simultaneous tax examinations, safe harbor rules, recommendations in relation to APAs and arbitration.

Within the compliance practices area, the Guidelines cover examinations (i.e. transfer pricing audits), and provide guidance on the burden of proof and on the application of penalties. For audits, a flexible approach which does not demand unrealistic precision is recommended; tax examiners are encouraged to take into account the taxpayer's commercial judgment about the application of the arm's length principle. The Guidelines recognize that the divergent rules on burden of proof among OECD member countries could present serious problems. The Guidelines refer to the commentary on the OECD Model to show how countries may overcome this problem. With regard to penalties, no overall recommendation is made, given that penalties are part of the broader tax compliance process. It is stated that the primary goal of penalties is to deter non-compliance, and that OECD member nations should not apply harsh penalties where taxpayers have made good faith attempts to comply.

The interaction of different tax administrations in the transfer pricing area is covered by the discussion on mutual agreement procedures and corresponding adjustments. The analysis commences from Arts. 9 and 25 of the OECD Model and covers concerns with the procedures and guidance on solutions, including the possibility of arbitration. Guidance is provided on applicable time limits, suggested duration of mutual agreement proceedings, the involvement of the taxpayer in the process and publication of applicable procedures. Problems concerning collection of tax deficiencies, accrual of interest, and the challenges of secondary adjustments are also discussed.

A simultaneous tax examination is defined as an "arrangement between two or more parties to examine simultaneously and independently, each on its own territory, the tax affairs of (a) taxpayer(s) in which they have a common or related interest with a view to exchanging any relevant information which they so obtain".10 The Guidelines cover the legal basis for simultaneous tax examinations (Art. 26 of the OECD Model) and provide recommendations on the use of processes.

The concept of safe harbor is explained by reference to general tax law of the country concerned.

A safe harbor is thus a statutory provision that applies to a given category of taxpayers which relieves eligible taxpayers from transfer pricing related obligations imposed by the tax code by

substituting exceptional, usually simpler obligations. In a transfer pricing context, this can vary from a total relief of targeted taxpayers from the obligation to conform to a more limited relief, with the obligation to comply with procedural rules as a condition for qualifying. The OECD Guidelines discuss factors supporting the use of safe harbors and the benefits for both taxpayers and tax administrations in using them. There is also a review of potential problems presented when using of safe harbors including potential non compliance with the arm’s length principle, and the risk of double taxation and difficulties with the mutual agreement procedure. Treaty Aspects

Tax treaties are the main instruments for governments in dealing with cross border tax issues and allocation of taxing rights to the same income. Tax treaties thus impact transfer pricing treatment, since the amount of taxable income in a particular country is determined by reference to the arm’s length principle. Article 9 (associated enterprises) of the OECD Model provides that "when conditions are made or imposed between associated enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which would be made between independent enterprises, then any profits which would, but for those conditions, have accrued to one of the enterprises but by reason of those conditions, have not so accrued, may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly." In other words, if the nature of the relationship between the related parties influences the levels of profit attributable to any of the parties, the state that has taxing rights to those profits can adjust profits by reference to the arm’s length principle and tax such additional profits. The current version of the Guidelines cites Art. 9 as the authority for the arm's length principle.

The OECD Model has some other provisions of particular importance in dealing with transfer pricing issues:

? Art. 5 which defines a permanent establishment;

? Art. 7 (the business profits article) which limits to the arm's length amount the attribution of

taxable profits to a branch or other permanent establishment;

? Arts. 11(6) and 12(4) which limit relief from tax on interest and royalties, where a special

relationship exists between the payer and the recipient;

? Art. 23 which provides for the elimination of double taxation;

? Art. 25 which provides for a mutual agreement procedure between the competent

authorities of the treaty partners and an arbitration procedure if the competent authorities do not reach agreement on one or more issues; and

? Art. 26 which provides for exchange of taxpayer information between those competent

authorities.

In general, however, only a smaller number of treaties contain language following Art. 9(2) of the OECD Model regarding a corresponding adjustment.

The Guidelines comment on the advantages of including in an article on the mutual agreement procedure a paragraph similar to Para. 5 of Art. 25 of the OECD Model. Without the provision for

arbitration, the competent authorities may endeavor to reach agreement but if they cannot agree there is no mechanism to resolve the issue. Where the arbitration paragraph is inserted into a treaty, resolution is still possible by taking the issues to arbitration. Under the provisions of Para. 5 of Art. 25 where the competent authorities cannot reach agreement on one or more issues they may be submitted to arbitration, and this possibility therefore makes the mutual agreement procedure more effective. The existence of an arbitration procedure that gives greater opportunities to resolve the issues may encourage taxpayers to use the mutual agreement procedure more frequently even if arbitration is ultimately not required. Governments would also have an incentive to conduct the mutual agreement procedure more effectively so as to resolve the issues without the need to go to arbitration.

Advance Pricing Agreements

An APA is defined as “an arrangement that determines, in advance of controlled transactions, an appropriate set of criteria (e.g. method, comparables and appropriate adjustments thereto, critical assumptions as to future events) for the determination of the transfer pricing for those transactions over a fixed period of time.”11 The Guidelines provide some approaches for legal and administrative rules governing APAs and set out the possible risks and benefits of such arrangements. The OECD has found that member states that have experience of APAs are generally satisfied with them; and the Guidelines make recommendations for setting up an efficient APA process. These include coverage of an arrangement, completion of bilateral or multilateral APAs where possible, ensuring equitable access to APAs for all taxpayers and developing working agreements between competent authorities and improved procedures.

With regard to the scope of an APA, the Guidelines point out that the attention must be given to how reliable are the predictions made in preparing the APA. The reliability of a prediction depends on the critical assumptions that it is based on. The critical assumptions should take into account potential changes in conditions, such as the functions performed by related enterprises or external conditions such as movements in interest rates. The reliability of predictions is dependent on the particular circumstances and this must be taken into account when determining the scope of the APA. It is generally more reliable to make predictions about the suitability of a transfer pricing method and the application of the method rather than predicting future profit levels or prices.

The Guidelines recommend that, if possible, an APA should be bilateral or multilateral in nature based on the mutual agreement procedure of the relevant tax treaties. A bilateral APA is preferable to a unilateral APA where the taxpayer may feel pressured to conclude the agreement or accept a non-arm’s length agreement so as to avoid expensive enquiries by the tax authorities with the possibility of penalties. In the case of some tax administrations it may not be possible to conclude unilateral APAs because there is no domestic legislation allowing for binding agreements with the taxpayer.

The Guidelines point out that although in practice APAs may effectively only be available to large taxpayers, there is an issue with respect to equality of treatment between taxpayers. The tax administration should be prepared to allocate resources in a way that allows access to APAs by smaller taxpayers and consider the possibility of streamlined access that reduces costs. The level

of enquiries made by the tax administration in connection with APA applications should be adapted to the number of international transactions engaged in by the taxpayer.

The Guidelines also suggest working agreements between tax administrations for undertaking APAs, which should include guidelines for reaching mutual agreement where the taxpayer has requested an APA on transfer pricing issues. The Guidelines should also apply to the conclusion of bilateral APAs with treaty partner countries. The same information should be available to the tax administrations at the same time and the methodology agreed between them should conform to