SK-II 精研祛斑精华液

SK-II Whitening Spots Specialist

说是去斑的,其实美白功能差不多的吧,环彩美白精华用了3个礼拜没什么效果之后,开了这瓶用,同样是配神仙水、骨胶原乳液,到现在2个礼拜,白了一些,效果还是蛮明显的。透明的GEL质地,但是胶质成份也并不多,无色无味的样子,用得多了也没有什么不良反应。

不过清莹爽肤水不敢多用了,每次涂上渗进皮肤都会轻微刺痛,都没用化妆棉擦,光用神仙水当爽肤水用的话刺痛没那么明显,但是也比较干的,没有油份。这段时 间除了下雨的那几天,天气真的非常干燥,每次都涂很多神仙水和骨胶乳液,也只是勉强维持不会干燥到紧绷起来,保湿度还是不够。

怪不得以前听说过一种讲法,说是SK2的神仙水Pitera系列,最适合给油性皮肤的MM用,控油调节功能很好,以前一直觉得要是光靠护肤品,控制皮肤毛孔的油脂分泌和排泄是无稽之谈,一个多月用下来,感觉到Pitera能调节皮肤机能、控油之类的说法还是有一定的道理。

这个去斑精华的成份比较诡异,一直说日本产品的列表排列不是严格按照成份比例大小来排的,下面是在一家美国的购物网站列的成份,在要求完全公布成份的地界,小日本应该不敢做什么鬼吧

但是网上流传的其他列表有把Pitera放第一位,VC糖放第三位的,一个MM从亚洲卖的产品盒子上抄的版本是Pitera放第一位,VC糖跟我列的版本 差不多在末位,但是那些版本里几个植物成份靠中段,不像这个都在靠后位置。整个成分表植物精华成份很少,其他的也就是一点玻尿酸了。

既然功效还不错,可能VC糖实际比较多?不过也可能是没有氢氧化钠,加上那个有些甘草衍生物的成份,我的脸就对Pitera良性地反应出效果了。

总体感觉其实没有以前常用的兰蔻美白精华好,但是这个毕竟不痛不痒,兰蔻美白涂太多了毕竟痒痒的,也只能在家涂厚一点,氧化了黄不拉几的,出门就不能多涂 了,这个可以随心所欲涂厚一些。娇兰的滢珠百合美白精华其实质地也挺像,但是折扣没有这个那么大,下次还是兰蔻或者娇兰吧,这个去斑精华也并没有太大的优 势。

全成份

水, Pitera, 烟酰胺, 丁二醇, 戊二醇, 聚甲基硅倍半氧烷, 肌醇, 硅灵, 异十六烷, 植物甾醇/辛基十二醇月桂酰谷氨酸酯, 丙烯酸/C10-30烷基丙烯酸聚合物, PEG-20 失水山梨糖醇椰油酸酯, 苯甲酸甲脂, 氨甲基丙醇, 苯甲醇, 聚二甲基硅氧烷醇, 甘草酸钾, 乙二胺四乙基二钠, 黄原胶, 苯甲酸钠, 玻尿酸钠, 掌叶树, 维他命C配糖体, 燕麦

第二篇:SK-II Case

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 BEAUTY AND THE BEAST: CONSUMER STAKEHOLDERS DEMAND

ACTION IN CHINA

Gail Whiteman

Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Barbara Krug

RSM Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands and University of Manchester,

Manchester, United Kingdom

Abstract: Academic conceptualizations of corporate social responsibility rarely

take an institutional perspective. Yet, the socially responsible behavior of

multinational companies in China cannot exist within an institutional vacuum. We

address this gap in the literature by presenting the case of SK-II Cosmetics,

manufactured by Procter & Gamble in Japan and exported to China. In 2006,

Chinese authorities announced that SK-II contained toxic chemicals despite

company denials. Using SK-II as an exemplary case, we argue that dynamic

institutional actors, such as the state, media and consumers continually shape and

challenge the definition of what is socially responsible behavior, based not just on

firm’s behavior but on the broader institutional context. We suggest that at least

three institutions are important in determining corporate social responsibility for

foreign firms in China: first, the market (more precisely competition); second,

political/private censorship of information (or the tactical use of misinformation)

and corporate governance; third, state protectionism and rent-seeking.

Keywords: corporate social responsibility, institutions, China Procter & Gamble

skincare

INTRODUCTION

The overly prominent role moral hazard or opportunism plays in New Institutional Economics1 has often left students of organizational theory wondering why there are so many firms which actually treat their employees, suppliers or customers fairly or do not harm the environment, even when they know they could get away with it. The call for more corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the recent scandals in multinationals notwithstanding, we know that not all firms lack CSR. Ever since de Soto analyzed whether one can start or run a business (in Peru) by playing by the rules, attention has been drawn to the fact that CSR is a phenomenon that is restricted neither to multinationals nor to the “Western” industrialized world (de Soto, 1989).

In what follows we claim that an institutional perspective is missing in the CSR-literature (Campbell, 2006) which models organizational behavior almost exclusively via the interactions between the firm and its stakeholders. Instead it is assumed in what follows that CSR depends on a set of institutions which reward responsible behavior and mobilize resources for investing in such behavior (Campbell, 2006). We also contest the comparative static view in which institutions are conceptualized 36

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 as non-dynamic constraints for individual or collective decision making. Such studies overemphasize the role of (usually exogenously given) cultural norms and state legislation, while neglecting the influence of market forces, such as competition and corporate governance. For example, studies neglect to explore the interaction between the management and share-/stakeholder, and political agencies. The co-existence of firms with high CSR and those with low CSR working in the same country and economic regime asks for an explanation that goes beyond the cultural and political context.

A dynamic perspective promises insights relevant for all transitional economies where political and economic actors still search for institutions that define “defaults” for the range of economic action that obeys nothing but a functioning price mechanism (Meyer & Peng, 2005). To blame either too “liberal” markets or the socialist legacy for the lack of CSR in the new private sector does not do justice to the millions of firms in, for example China, which neither exploit their workforce nor pollute the environment. From a dynamic perspective the question is rather whether these firms can survive in the long run or, more generally, which institutions are needed to make CSR a business strategy which promises positive returns. After a short review of the literature on CSR, we present a much publicized case of SK-II skin care in China before offering an economic interpretation and insights from New Institutional Economics that go beyond the case. The analysis ends with some general conclusions, where we suggest that at least three institutions are important in determining corporate social responsibility of foreign firms in China: first, the market, more precisely competition; second, political/private censorship of information (or the tactical use of misinformation) and corporate governance; third, state protectionism and rent-seeking.

CONSUMERS AND STAKEHOLDER THEORY

Research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and international firms is growing (Christmann &Taylor, 2001; Dowell et al., 2000; Husted & Allen, 2006; Kolk, 2005; Kolk & Van Tulder, 2004; Schlegelmilch & Robertson, 1995; Strike, Gao & Bansal 2006; Van Tulder & Kolk, 2001). Yet the concept of CSR has been in existence for half a century, when Bowen (1953) first published “Social Responsibilities of the businessman.” Bowen argued that business executives have a strategic role in society, and that managerial decisions have important impacts on the general welfare of citizens and society at large. Since that time, CSR has evolved in a diffusion of corporate codes and programs, yet remains a subject of wide debate. For instance, does CSR encompass only voluntary social or environmental actions (European Commission 2001), or does CSR encompass a wide spectrum of economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic behaviors (Carroll, 2004)? In general, there is much support for the idea that CSR encompasses “actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm that which is required by law” (McWilliams & Siegel, 2001, p. 117). Yet Porter & Kramer (2006) argue that most of the prevailing justifications for CSR focus on the tension between business and society rather than on their interdependence.

Further, typical theories of CSR develop only a generic rationale for the concept not explicitly tied to the strategy and operations of a specific company or the countries in which it operates. Porter & Kramer (2006) reiterate Bowen’s original strategic focus, and caution that a lack of strategic integration will result in CSR practices and initiatives isolated from operating units, leaving the firm vulnerable to strategic threats and externally diffusing the firm’s societal impact.

37

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008

A lack of strategic integration challenges multinational firms who must deal with both global and local issues within their CSR approach (Husted & Allen, 2006). Global CSR is a response to universal principles (or hypernorms) and “deals with a firm’s obligations based on those ‘standards to which all societies can be held’” (Husted & Allen, 2006, p. 840). Examples of global societal issues may include human rights, environmental protection, and possibly consumer health & safety. In contrast, local CSR “deals with the firm’s obligations based on the standards of the local community” (Husted & Allen, 2006, p. 840). Thus the global and local social context should have relevance to effective firm behavior.

Research indicates that multinational firms face many challenges in developing and implementing effective CSR policies and programs. For instance, a recent McKinsey study concluded that, “Executives around the world overwhelmingly embrace the idea that the social role of a modern corporation goes far beyond meeting its obligations to shareholders…Yet executives, wary of the risks such obligations bring, say that their companies aren't adept at anticipating or managing social obligations.”2 Furthermore, while there is the opportunity for firms to develop a strategic approach to global-local CSR (depending upon the global and local context), research indicates that firms tend to be non-strategic and develop CSR approaches based on internal isomorphic pressures rather than reflect the external social context (Husted & Allen, 2006).

However, other studies indicate that multinational firm behavior can be context-specific in terms of cultural differences and varying stakeholder pressures (Chapple & Moon, 2005; Logsdon et al., 2006). Waldman, et al., (2006) has also illustrated that culture can affect managerial perceptions and CSR behavior. Differences exist within the Anglo-Saxon countries (Maignan & Ralston, 2002) and within Europe (Schlegelmilch & Robertson, 1995). Asian perspectives on CSR also tend to differ. For instance, Wokutch (1990) argued that Japanese firms were more advanced in cooperative labor relations and with occupational safety and health issues than US firms. Welford (2005) shows that a CSR focus has rapidly grown among Asian firms and that Asian firms target different issues than their European or North American counterparts. Asian firms pay less attention to general social or environmental issues when compared with multinationals from Europe or North America, and tend to have a narrow definition of stakeholders as customers and shareholders (Lines, 2004). CSR reporting also has regional differences in both frequency and content (Fortanier & Kolk, 2007; Jose & Lee, 2007; Kolk, 2005). There also appears to be an internationalization effect of CSR practices. For instance, Chambers, et al., (2003) analyzed 350 companies operating in Asia, and found that firms which operate internationally are more likely to engage in CSR and to institutionalize it through codes.

Research also indicates that firms pay attention to social and environmental issues depending upon its relevance to key stakeholders, but may do so in symbolic and/or substantive ways depending upon the degree of monitoring and sanctions for non-compliance (Christmann & Taylor, 2006). Broadly speaking, a stakeholder is “any individual, community or organization that affects, or is affected by, the operations of a company” (Freeman, 1984). However, firms tend to pay attention to a subset of stakeholders, and core stakeholders are those that have measurable salience to managers (Mitchell, et al., 1997). Stakeholder salience depends upon their degree of power, urgency and legitimacy to the firm and/or other powerful actors (Mitchell, et al., 1997). Stakeholders do not act alone; previous research has recognized the powerful networking ability of a vast range of stakeholders (Rowley, 1997). Thus stakeholder groups that may appear to have little direct power can undertake a variety of strategies to 38

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 gain greater influence over firm behavior (Frooman, 1999). From a stakeholder perspective, the socially responsible firm recognizes “that day-to-day operating practices affect stakeholders and that it is in those impacts where responsibility lies” (Andriof, et al., 2002).

Consumers are commonly identified as important stakeholders by firms, particularly in consumer package goods sectors. While consumers collectively have significant purchasing power, individually they often lack access to detailed information on social and environmental issues related to the products that they purchase. However, consumer information alone is usually insufficient to safeguard consumer rights and health and welfare (Thorelli, 1978). Thus, consumers typically require intermediary organizations which provide monitoring of firm performance and sanctioning of non-compliance. Consumer support for, and interest in, CSR has been researched in the US and Europe but to date there is little information on Chinese consumer behavior concerning CSR issues. However, we do know that many consumers in the US and Europe say that they prefer to buy from socially responsible firms (Maignan, 2001; Wocester & Dawkins, 2005).

Despite the recognition that CSR is an outcome of societal expectations, there has been little previous use of institutional theory to conceptually or empirically explain how stakeholders and firms interact within larger institutional frameworks and organizational fields (Campbell, 2006). However, recent conceptual and empirical studies (Campbell, 2006; Husted & Allen, 2006) suggest that institutional theory has much to offer in terms of explaining why firms engage in CSR activities. Campbell (2006) argues that institutional theory can provide a conceptual frame to better understand how institutional incentives and constraints result in CSR policies and activities by firms. That is, institutional theory can help explain why some firms behave responsibly (or not) given the organizational field in which they operate. Husted and Allen (2006) apply institutional theory from within the firm’s boundaries in order to see how isomorphic pressures permeate different functional areas. Their empirical study in Mexico demonstrates that the organizational strategy of multinational companies can significantly influence CSR behavior because of institutional processes: that is, firms choose CSR policies and actions that tend to fit with existing firm-behavior in other realms (e.g., product-market activities).

To date, no empirical research examines how external institutional dynamics at the organizational field level may impact firm legitimacy as a socially responsive actor, regardless of actual firm behavior. An intriguing related question is: why do other institutional actors support or challenge the legitimacy of a firm’s CSR reputation and activities? In what follows we suggest that New Institutional Economics (NIE) can identify patterns in the behavior of major economic agents, such as stakeholders, firms, or state agencies. The case that will be described presently focuses on an event (or more precisely, a crisis) that exemplifies the interaction of agents and institutions. This paper examines how institutional dynamics shapes CSR legitimacy when institutional dynamics may not initially trigger changes in firm behavior.

39

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008

THE CASE

China is a key market for the international cosmetics industry. Faced with a mature or declining European and North American markets, companies are aggressively pursuing the Chinese beauty market. Currently, Chinese women spend less than their Asian counterparts. For example, Euromonitor (2007a) estimates that the “Average annual per capita spending on cosmetics and toiletries in China is just $8 US dollars (¥65 RMB), five times lower than the global average of $40 US dollars and far below that of its developed neighbor Japan or the United States of $248 US dollars (¥26,672).”

However, the annual per capita spending changes dramatically alongside China’s rapid GDP growth. Chinese women are becoming increasingly important consumers in their own right, with average female disposable income increasing by nearly 50% to $520 US dollars or 52 euros (RMB 4, 264) a year in 2005 (vs. 2001) (Euromonitor, 2007a). Chinese women, like women around the globe, are willing to spend sizeable amounts of their disposable income on premium cosmetics. By 2004, China became one of the global top 10 cosmetics markets, one of the top 5 growth markets, and 2006 estimates of total sales were at $1.3 billion US dollars (RMB10.5 billion) (Euromonitor, 2007a). Sales are expected to rise by +10% annually until 2010, with an estimated market value of $17 billion US dollars (RMB139.8 billion). Modern retail distribution has also grown significantly alongside consumer demand. Major Chinese cities like Shanghai have extensive networks of department stores and specialty retailers like Sasa, Sephora and Herborist. (Herborist is a natural cosmetics manufacturer which mixes modernity with Chinese herbal tradition and has been called the Body Shop of Asia (Chinese website .cn.)

Growing demand for cosmetics in China represents a significant shift in consumer behavior. According to Fortune magazine (Prasso, 2005), “China is a country where barely any women used cosmetics a decade ago. When the authorities stopped discouraging lipstick and other bourgeois displays of beauty in the early 1990s, Chinese women were eager to embrace the aesthetics of the modern world. As a result, the beauty industry has been growing at breathtaking speed …

Some 90 million urban women in China spend 10% or more of their income on face cream, lipstick, mascara, and the like, particularly in fashionable Shanghai, where women spend 50 times more per capita on cosmetics than women nationwide.” For example, skin care brands, like Procter & Gamble’s SK-II, account for over 70% of China’s premium cosmetics sales. Within this market, Chinese women are interested in brands that can convey “status” and a prestige-image (Zheng, 2003).3 Western brands have thus done well, and many Chinese shoppers are prepared to pay premium prices (above international prices) in order to ensure that they are not buying “knock-offs.” However, Western firms are under increasing pressure by domestic Chinese manufacturers (Euromonitor, 2007b). Table 1 describes skin care companies’ market shares.

40

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 Table 1

Skin Care Company Shares by Retail Value 2002-2006

Procter & Gamble (Guangzhou) Ltd

L'Oréal China

Amway (China) Co Ltd

Shiseido Liyuan Cosmetics Co Ltd

Avon (China) Co Ltd

Jiangsu Longliqi Group Co Ltd

Unilever China Ltd

Beijing San Lu Factory

Hangzhou Mary Kay Cosmetics Co

Arche Group Co Ltd

Elca (Shanghai) Cosmetics Ltd

Source: Euromonitor International (2007b) 12.5 14.8 17.0 17.5 16.3 4.5 5.7 10.5 11.3 11.8 8.0 9.7 13.1 10.7 7.9 6.4 6.4 6.6 6.9 7.3 6.7 6.9 8.3 7.0 6.5 5.4 5.0 4.8 4.7 4.7 4.4 4.2 3.6 4.1 4.2 4.6 4.5 4.2 3.6 3.6 2.4 3.2 4.1 4.5 3.3 2.4 2.4 2.4 2.4 2.3 0.8 0.9 1.4 2.0 2.2

Procter & Gamble (P&G) has long been the dominant international player in the industry. According to Fortune magazine (Prasso, 2005), Procter and Gamble primarily holds this position because “its Olay whitening skin creams outsell every other brand, and its shampoos (Rejoice, Head & Shoulders, and Pantene) hold the top three hair-care positions in China.”4 Globally, P&G positions itself as a leader in CSR, and has been identified as one of Asia’s most socially responsible companies. However, the company has faced international civil society campaigns which challenge its claim of socially responsible behavior. Nevertheless, sales of SK-II, its premium skin care line, have been growing since its introduction into the Chinese market.

The story of the SK-II discovery, available on the P&G website, is fitting for an Asian beauty product: scientists supposedly discovered this beauty secret when they realized that workers at a Japanese sake brewery had remarkably young hands despite their biological age. Testing of sake eventually resulted in discovery of the ingredient Pitera, which the SK-II premium skin care line now contains. SK-II is still manufactured in Japan and imported to China. With strong celebrity endorsements from global stars such as Cate Blanchett, SK-II hit a cord with the Asian and Australian markets. From 2003-2005, SK-II market share grew from 1.1% of the total market to a steady 1.8% (Euromonitor, 2007b). Yet in September of 2006, Procter & Gamble was forced to suspend sales of SK-II, its high-end consumer skin care line following media allegations that government testing had identified that the product contained toxic ingredients which may cause eczema and asthma.

On September 14, Chinese media reported that the Guangdong Center for Inspection and Quarantine had detected banned heavy metals in SK-II products, and that the Chinese General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) had reported this to its Japanese counterpart, since SK-II is manufactured in Japan and then imported to China. The situation 41

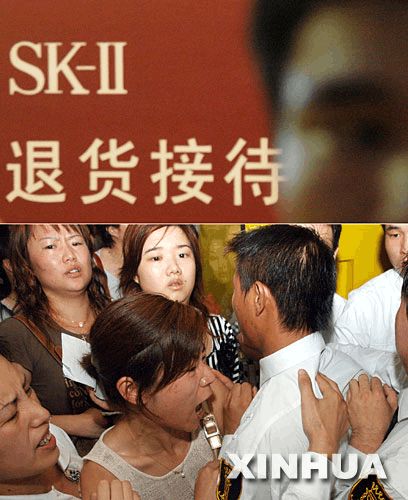

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 worsened when the Shanghai Municipal Food and Drug Supervision Administration announced state testing had discovered chromium and neodymium in three other Japanese SK-II cosmetic products. The Administration claimed that studies showed that some SK-II products contained traces of neodymium and chromium, substances that above trace levels may pose health risks such as eczema and allergic dermatitis.5 Media reports stated that: “In Shanghai the administration called in senior management from Japan-based SK-II producer Procter & Gamble, informing them of the finding and requiring them to take all 12 products off the counter.”6 The Shanghai Administration for Industry and Commerce’s website demanded that SK-II products be removed from retail shelves and refunds offered immediately.7 In addition to state intervention, angry Chinese consumers also demanded that they be compensated (see Appendix 1).

Initially, P&G offered refunds to consumers in the form of a so-called “safe-product” agreement. However, in order to receive a refund, consumers had to sign a waiver stating that they recognized the products presented no harmful effects. They also were not given a refund immediately even if they had to return their unused product (/article/20248.) Later that same month, the media reported that the Chinese Consumer Association (CCA) said that “consumers are entitled by law to demand that substandard products be recalled unconditionally.”8

Furthermore, CCA spokesman Wu Gaohan explained that “Any new conditions that the company

[P&G] tries to impose are either invalid or illegal…Consumers have to learn to protect their own rights and interests.” P&G later suspended its refund policy as thousands of consumers tried to request refunds. The suspension of the refund policy caused further backlash. According to China Daily, consumers were outraged: “Who should be responsible for our loss?”9 The media also reported that “P&G's Chinese website was hacked and clashes broke out at some of its stores.” An internet poll taken by a popular website Sina.com, showed that 98.8% (of nearly 150,000 people) said they would not buy SK-II products in the future. China Daily also reported that consumers were critical of the state’s quality inspection.

The issue spread throughout Asia, with consumers and retailers voicing concern over the safety of SK-II. SK-II consumers in non-Asian countries such as Australia were also debating the safety of the product line (see blog on Vogue Australia website). Throughout the ordeal, the Chinese media consistently focused on the Japanese manufacturing location, not on the location of the US head office, using headlines like “Substandard Japanese cosmetics asked to be recalled.”10 The Chinese media also suggested that Japanese authorities had admitted that the product had not been subject to quality testing prior to export to China. In contrast, Japanese media speculated that the critical Chinese allegations served as a retaliatory move by the Chinese state following Japan’s strengthened prohibition on toxic chemicals in Chinese food imports (personal interview July 2007; also see ). Throughout the crisis, Procter & Gamble denied that SK-II was unsafe and emphasized the company’s technical expertise as well as the approval by other international safety standards:

“We're completely confident in the safety of SK-II. SK-II products comply with safety

standards and regulations set by the FDA, HealthCanada, and the E.U.

42

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008

The Chinese government recently raised questions about 2 elements found at trace levels

in SK-II products. SK-II does not add these elements as ingredients in any of our

products. It is common for trace amounts of these minerals to show up in consumer

products -- they are naturally occurring elements that can be found in anything from tap

water to vitamins. For example, the amount of chromium that you would get from use of

SK-II products is 100 times less that what the World Health Organization considers safe

in your everyday diet.

P&G product safety scientists conducted analyses of SK-II products and have concluded

that the levels reported by the CIQ do not represent a safety concern. Our testing also

included other popular skin care brands and showed they, too, contain similar low and

safe levels of these trace elements.

SK-II has strict quality control processes in place and consumers around the world can

continue to use SK-II products with full confidence. If you have further questions about

SK-II products, please contact an SK-II representative at your local retailer.”11

The protests of angry consumers were reported in the Chinese press, as the press also showed pictures of angry consumers. The issue of the protests was “taken up” by state agencies responsible for the health related issues and led to a general discussion about the cosmetic industry, if not health hazards in general. The rapidly increasing use of websites ensured that consumers’ voices could be picked up by consumers outside China as protestors posted their protest on blogs and BBS. In late October 2006, the AQSIQ and the Ministry of Health of China jointly stated that the P&G products were safe although there was no admission of error on their part. The Taiwanese Department of Health, the Hong Kong Custom and Excise and Department of Health, the Singaporean Health Sciences Authority, and the Korean Food and Drug Administration issued statements attesting to the safety of SK-II. Nevertheless, SK-II’s market share collapsed by 50% to only 0.9% in 2006. Procter & Gamble’s website in the UK continues to have questions about SK-II’s safety at the topic of the list. Sales of SK-II resumed in China in December 2006.

This case had far reaching effects beyond Procter & Gamble’s drastic fall in revenue and market share. Although the allegations were later rescinded, the case affected the reputation of the industry in Asia. According to Euromonitor (1007b), the entire premium skin care market in China was impacted by the scandal with growth slowing considerably in 2006. In May 2007, a spot-check by China's Ministry of Health found that 10.5% of imported cosmetics and 8.3% domestic products failed to meet quality standards.12

DISCUSSION

SK-II is an exemplary case for demonstrating the power of institutional dynamics on foreign firm legitimacy even though the SK-II crisis may, at first glance, appear to be a somewhat trivial case about the ugly side of beauty products (and the possible existence of toxic metals in skin care creams.) We argue that the SK-II case illustrates how Chinese institutions allow state agencies to actively resist “foreign” products by presenting test results in negative ways. Taking a different interpretive lens, the 43

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 Chinese authorities could have come up with a different plan of action. However, they chose to go to the media with a negative story about the poor CSR performance of a foreign multinational.

On the surface, the critical issue may appear to be one of science: that is, one must determine the scientific facts of the case -- are skin care products safe for Chinese female consumers? Digging below the surface, we see that the SK-II case is actually a dynamic story of many local Chinese state agencies interpreting test results in a negative way. These testing interpretations may relate to broader issues of international trade and the Chinese reaction to external criticism of China’s own reputation concerning consumer health and safety testing. Examples of recently criticized products include Chinese-produced toys and toothpaste. That is, if foreign manufacturers (and foreign countries) are negligent or socially irresponsible with consumer health and safety testing, this provides greater institutional space for China itself to deal with its own internal weaknesses concerning consumer health and safety testing. While Procter & Gamble consistently denied that they had added toxic substances to their product line, these facts are not important (at least for a time) within the Chinese institutional arena. What is more important is the recognition that local agencies can interact to redefine socially (ir)responsible behavior and thus influence a firm’s legitimacy regardless of actual firm behavior.

Using SK-II as an exemplary case, we argue that dynamic institutional actors such as the state, media and consumers continually shape and challenge the very definition of what is socially responsible behavior, based not just on firm behavior but on the broader context. The contribution of an institutional analysis is that it draws attention to the fact that CSR is shaped by institutions that have emerged in Western market economies. Seen from the perspective of transitional economies such as China, CSR describes different courses of action within the defaults set by national or international legislation and long-established business practices. Likewise, whether an economic or social actor is a stakeholder is defined by legal “empowerments,” that is, the rights to assemble and publish unfavorable data and mobilize support. All this is still missing in transitional economies which are still at the stage of “negotiating” appropriate, socially responsible behavior in market transactions.

In such a situation, any analysis of CSR inevitably asks for a broader contextual analysis acknowledging more actors than the usual stakeholders, and including more courses of actions. In other words, so long as national or international legislation has not yet defined the defaults for socially responsible behavior (and standards of monitoring) within the economy, a very broad organizational field emerges. Indeed, CSR turns into a public policy issue: CSR legitimacy for one firm turns into a problem of “active” trade policy at the state level possibly across many firms or industries; health concerns about a specific consumer product become intertwined with broader issues such as the question of non-tariff trade barriers.

The SK-II case demonstrates how a firm’s reputation may become damaged (and perceived as a socially irresponsible company) not because of anything they have done (per se) but rather because P&G did not adequately anticipate, or react to, externally-driven institutional dynamics that arose beyond its immediate organizational field of cosmetics. Thus, the SK-II case also has important implications for the strategic management of CSR in multinational firms.

While Husted and Allen (2006) argue that the key strategic question facing multinational firms is to adequately distinguish between global and local issues and then to strategically respond to these issues, our case highlights an additional strategic element. In the SK-II case, consumer health and safety 44

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 concerns appear as a global issue that Procter & Gamble attempts to address strategically in a globally standardized fashion, ensuring that their performance in China, a developing country, is at least as good as in the developed countries/regions of the US, the EU, and Canada. We suggest that firms must distinguish between global and local institutional set ups and respond accordingly.

In the SK-II case, Procter & Gamble consistently tried to react to what it considered a global issue of product testing standards, and ineffectively addressed China’s concerns by publicly refuting these concerns and instead using test results issued under other ‘foreign’ standards. Yet whether these international standards were acknowledged by Chinese institutions was far from clear. A more effective strategy for Procter & Gamble may have been to publicly accept the seriousness of the concern and thus bolster the local legitimacy of the Chinese health agencies while at the same time working (possibly behind the scenes) to change perceptions of the Chinese administration or address procedural errors in testing. Thus a strategic approach to CSR necessitates a differentiation between global and local issues and between global and local institutional set ups which may have the power to shape perceptions of social responsibility or irresponsibility at the local level.

THE INSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE: GENERAL IMPLICATIONS

The case is instructive so far because it shows that institutions matter – a firm’s CSR legitimacy is actively shaped by institutional dynamics beyond its control and immediate sphere of reference. We suggest that at least three institutions can be identified which explain the behavior of the major players: first, the market, more precisely competition; second, political/private censorship of information (or the tactical use of misinformation) and corporate governance; third, state protectionism and rent-seeking. Employing market theory and the findings of NIE offers more than an economic interpretation of the SK-II crisis. As will be shown presently, by pointing to the logic behind the behavior of each player, such an analysis allows for the cautious formulation of a hypothesis about the consequences of the institutional set up on the emergence and survival of firms with a high (or low) level of CSR awareness or performance.

Although the economic reforms in China have led to widespread decentralization of decision making power, and the emergence of private ownership, reforms have not directly led to the furtherance of consumers’ rights. Typically, the consumer is nowhere to be seen in economic policy, hidden behind statistical categories such as “households,” or “peasants.” Only recently did the government pay attention to consumers, manifested in the form of residents in the new urban residential areas. These residents express their demands for schools, public traffic, parks, shopping malls and health care, predominantly voicing their demands through their work units which still control the allocation of housing (Li, 2000; Wang, 2001). Thus, from a stakeholder perspective Chinese consumers are at best, emerging stakeholders, and often remain dormant actors because of historical institutional constraints. Yet, that must not mean that they are powerless.

As market theory has shown, one producer with a high level of CSR would already be enough to effectively harm the market share of all producers using toxic substances. The effect will be more drastic the lower the costs for consumers who switch to another brand. The price differential between, say, Procter & Gamble and L’Oreal products, is almost zero in our case. Therefore, enough consumers will change their buying habits to cause damage in sales, market share and profit to Procter and Gamble. In 45

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 general, economics defines power as the reciprocal value of the price differential as compared to the next best alternative (the so-called opportunity costs) adjusted for the switching costs (Michael & Becker, 1973). The lower these costs the more influence consumers can exert. In other words: the availability of close substitutes, competition and low switching costs facilitates the emergence and survival of firms with a high CSR.

However, switching costs are not the only constraint on consumer action. In countries such as China where consumer rights have not been historically institutionalized, consumer power is constrained by state control. Thus, newly emerging consumer groups such as those in China may seek to exercise greater institutional power in situations where they have been granted the institutional space to do so: for example, with foreign firms offering consumer package goods products that are not integral to China’s economic growth. Unfortunately the same logic points to sectors where one must expect a large number, or high concentration of firms with a low CSR; namely industries where cartels – natural or state-enforced- preclude the emergence of close substitutes and define high (prohibitively high) switching costs. The scandals in China in sectors such as water supply, pharmaceuticals and the health care system offer ample evidence.

Consumers’ opportunity costs link to the problem of time and lack of information as consumers seldom have the time and money to test the cosmetics they are thinking of buying. As information and transaction cost theory have shown (Nelson, 1970; Williamson, 1985) asymmetric information allows firms to appropriate a greater part of the consumer rent (the so-called hold-up) to the extent that an active policy of information control might be a worthwhile endeavor. Our case is instructive in so far that the two different players pursued such a policy of information control. On the one hand, Chinese government agencies tried to “rig” the market by a policy of tactical misinformation about the health hazard. On the other hand, Procter & Gamble tried to “silence” protest by offering money.

The point to note here is that the futility of both attempts cannot be explained by changes in technology alone. While, indeed, the Internet keeps general information costs close to zero, the costs for verifying the source of information and its “truthfulness” can be prohibitively high – even without political censorship. The conflict spread worldwide as it is in the interest of all (potential) consumers to see the health hazard in cosmetics controlled. As democratic political regimes turn consumers into voters, the protest cannot be easily dismissed. And indeed, health agencies in the US, Japan, and the European Union tested the products disclosing the Chinese misinformation, while the media reported the Procter & Gamble scheme. Likewise, the US form of corporate governance turns consumers into stakeholders which can exert influence on the management of a firm.

It is also intriguing to speculate how much of the research and political pressure came from competing firms which anticipated the negative external effect when the reputation of the whole cosmetics industry appeared at stake. Thus, for example, L’Oreal published a statement in July 2007 insisting that their sun cream products have passed the tests not only by the US Food and Drugs association but also the Chinese Health inspection agency (/2007/07/05). Competing foreign firms seek to differentiate themselves from the SK-II case and resist isomorphic pressure. In addition, CSR legitimacy is gained not simply by complying with legal standards or through voluntary ethical or philanthropic initiatives (Carroll, 2004), but rather by anticipating and managing institutional dynamics that may not be directly related to actual firm behavior. The analysis expects us to 46

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 find more firms with a high CSR in sectors and countries where political and economic institutions such as corporate governance ‘empower’ consumer/voters to influence management decisions either directly or indirectly via political channels and the media.

The last argument points to the role of political actors in the case which needs to be seen as one period in a series of accusations by the Chinese, US, and Japanese governments. Both health concerns and “nationalism” are used for narrowly defined political ends. As the theory of protectionism has shown, health and quality standards are standard tools when governments want to limit imports while paying lip service to “free trade” (Milner & Yoffie, 1989). The attempt of the Chinese administration to prove the health hazard in imported cosmetics can be seen as a strategic move in the ongoing economic conflict with the US, Japan and the EU where the health hazard of Chinese products is regularly reported. In contrast, when the US administration tries to link product safety or piracy with macro-economic issues such as the exchange rate, than nationalism comes into play (The Economist, May 17th, 2007). As the theory of protectionism has shown, such behavior finds its explanation in the vested interest of producers and their link to political agencies. In short, these cases illustrate the impact of an institutional set up that facilitates rent-seeking by producers and firms rather than the influence of consumers or professionals, such as doctors. The number of firms with a high CSR would increase if the issue of CSR, or as in our case health concerns, would not be used for rent-seeking.

To sum up, the SK-II case exemplifies that three institutions matter when an economic system wants to secure a large enough number of firms with a high CSR: functioning markets with low entry and exit costs, an opportunity structure which offers means to consumers for influencing political and firms’ decision makers, and the destruction of rent seeking opportunities.

NOTES

1. New Institutional Economics mostly connected with Douglas North and Oliver Williamson has become a label-all approach that include institutions, whether state enforced, based on inter-active choice, or norms (Williamson 1985; North 2005.)

2. /article_abstract_visitor.aspx?ar=1741&L2=39&L3=29

3. Zheng, T.T. (2003). Consumption, body Image, and Rural–Urban Apartheid in Contemporary China. City & Society, 15, (2), 143-163.

4. The strongest competitor in China is L’Oreal which reckons with 15% growth rates for 2005, and 2006, see /home/feeds/afx/2006/02/23/afx2550236.html.

5. Banned Substances Found in 3 More SK-II Products.

/2946/2006/09/21/272@142138.htm.

6. Ibid.

7. Shanghai shops to remove SK-II products September 22, 2006.

.cn/200609/22/eng20060922_305381.html. Accessed 2006-07-16.

8. Substandard Japanese Cosmetics Asked to be Recalled. 2006-09-22. Xinhua. . Accessed 2006-07-16.

9. SK-II gets under consumers' skins September 25, 2006.

.cn/200609/25/eng20060925_306136.html. Accessed 2007-07-16.

10. http://www..cn/200609/22/eng20060922_305236.html.

47

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008

11. Procter & Gamble website for SK-II http://www.sk2.co.uk/showPage.do?section=faq.

12. /2007/05/14/1301-over-10-of-imported-cosmetics-fail-quality-test/.

REFERENCES

Andriof, J., Waddock, S., Husted, B., & Sutherland Rahman, S. (2002). Unfolding stakeholder thinking.

Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Bowen, H.R. (1953). The social responsibilities of the businessman. New York: Harper and Row. Campbell, J. L. (2006). Institutional analysis and the paradox of corporate social responsibility.

American Behavioral Scientist, 49, 925-939.

Carroll, A.B. (2004). Managing ethically with global stakeholders: A present and future challenge.

Academy of Management Executive, 18, 114-120.

Chambers, E., Chapple, W., Moon, J., & Sullivan, M. (2003). CSR in Asia: A seven country study of

CSR website reporting. International Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility, Nottingham

University, UK. Research Paper Series No. 09-2003.

Chapple, W., & Moon, J. (2005). Corporate Social Responsibility in Asia: A seven-country study of

CSR web site reporting. Business & Society, 44, 415-441.

China’s cosmetics and toiletries market gets posh. (2007a). Euromonitor.com. Retrieved February 21,

2007 from Euromonitor.com.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. (2001). Globalization and the environment: determinants of firm

self-regulation in China. Journal of International Business Studies, 32, 439-458.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. (2006). Firm self-regulation through international certifiable standards.

Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 863-878.

Country sector briefing: Skin care – China. Euromonitor.com. Retrieved June 2007 from

Euromonitor.com.

de Soto, H. (1989). The other path: The invisible revolution in the third world. New York: Harper &

Row.

Dowell, G., Hart, S., & Yeung, B. (2000). Do corporate environmental standards create or destroy

market value? Management Science, 46, 1059-1074.

European Commission. (2001). Green paper – Promoting a European framework for corporate social

responsibility.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Frooman, J. (1999). Stakeholder influence strategies. Academy of Management Review, 24, 191-205. Fortanier, F., & Kolk, A. (2007). On the economic dimensions of CSR: Exploring fortune global 250

reports. Business and Society, 46, 457-478.

Husted, B.W., & Allen, D.B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise:

Strategic and institutional approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 838-849.

Jose, A.,& Lee, S.M. (2007). Environmental reporting of global corporations: A content analysis based

on website disclosures. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 307-321.

Katz, J., Swanson, P., & Nelson, L. (2001). Culture-based expectations of corporate citizenship: A

propositional framework and comparison of four cultures. The International Journal of

Organizational Analysis, 9, 149-171.

48

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 Kolk, A. (2005). Environmental reporting by multinationals from the triad: Convergence or divergence?

Management International Review, 45(Special Issue 1), 145-167.

Kolk, A., & Van Tulder, R. (2004). Ethics in international business: Multinational approaches to child

labor. Journal of World Business, 39, 49- 60.

Lines, V.L. (2004). Corporate reputation in Asia: Looking beyond bottom-line performance. Journal of

Communications Management, 8, 233-245.

Logsdon, J., Thomas, D., & van Buren, H. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in large Mexican

firms. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 21, 51-60.

Maignan, I., & Ralston, D. (2002). Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the US: Insights from

businesses’ self-presentations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33, 497-514.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective.

Academy of Management Review, 26, 117-127.

Meyer, K.E., & Peng, M.W. (2005). Probing theoretically into Central and Eastern Europe: transactions,

resources, and institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 36, 600–621.

Michael, R.T., & Becker, G.S. (1973). On the new theory of consumer behavior.

The Swedish Journal of Economics, 75, 378-396.

Milner, H.V., & Yoffie, D.B. (1989). Between free trade and protectionism: Strategic trade policy and a

theory of corporate trade demands. International Organization, 43, 239-272.

Mitchell, R.K., Agle, B.R., & Wood, D.J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and

salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management

Review, 22, 853-887.

Nelson, P. (1970). Information and Consumer Behavior. The Journal of Political Economy, 78, 311-329 North, D. C. (2005). Understanding the Process of Economic Change. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

Porter, M.E., & Kramer, M.R. (2006). Strategy & society: The link between competitive advantage and

CSR. Harvard Business Review.

Prasso, S. (2005, December 12). Battle for the face of China. L'Oréal, Shiseido, Estée Lauder --the

world's leading cosmetics companies are vying for a piece of a booming market. Fortune

Magazine.

Rowley, T. J. (1997). Moving beyond dyadic ties: a network theory of stakeholder influences. Academy

of Management Review, 22(4), 887-910.

Schlegelmilch, B.B., & Robertson, D.C. (1995). The influence of county and industry of ethical

perspectives of senior executives in the US and Europe. Journal of International Business

Studies, 26, 859-881.

Shen, W. (2004). A comparative study on corporate sponsorships in Asia and Europe. Asia Europe

Journal, 2, 283-295.

Strike, V.M., Gao, J.J., & Bansal, P. (2006). Being good while being bad: Social responsibility and the

international diversification of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 37,

850-862.

49

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 The Economist. (2007). Retrieved May 17th, 2007, from

/research/articlesbysubject/displaystory.cfm?subjectid=478048&story_id=9184053.

Thorelli, H.B. (1978). Consumer rights and consumer policy: Setting the stage. Journal of

Contemporary Business, 7, 3-15.

Van Tulder, R., & Kolk, A. (2001). Multinationality and corporate ethics: Codes of conduct in the

sporting goods industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 32, 267-283.

Waldman, D., de Luque, M.S., Washburn, N., & House, R. (2006). Cultural and leadership predictors of

corporate social responsibility values of top management: A GLOBE study of 15 countries.

Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 823-837.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York and London: Macmillan. Wokutch, R.E. (1990). Corporate social responsibility Japanese style. Academy of Management

Executive, 4, 56-74.

Welford, R. (2005). Corporate social responsibility in Europe, North America, and Asia: 2004 survey

results. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 17, 33-52.

Wocester, R., & Dawkins, J. (2005). Surveying ethical and environmental attitudes. In Harrison, R. (Ed.),

The Ethical Consumer (pp. 189-203). London: Sage.

Appendix 1. Consumer Reactions to SK-II

50

Journal of International Business Ethics Vol.1 No.1 2008 Appendix 2

P&G Press release to Hong Kong consumers

(Hong Kong Custom and Excise Department & Department of Health Confirms that SKII Products are Safe and Not Harmful).

Dear Customers,

We are really grateful for your love and support for SK-II all along, we are very pleased to announce that:

1. Hong Kong Custom and Excise Dept & the Department of Health’s new testing results confirms that SK-II products are safe and not harmful.

2. With the principle that consumer always come first, SK-II puts safety and quality as our priority, all our products went through vigorous safety evaluation during research and production process, striving to bring the best quality products for our consumers.

For many years, SK-II never stops bringing you the promise of crystal clear skin. In this period of time due to consumers and retailer’s support & encouragement, allowing us to confidently stand by the promise from SK-II for our quality of products and services, we continue to create crystal clear’s beautiful miracle for you.

SK-II Consumer Hotline:

Yours,

SK-II

2006-09-23

51