Reading Report

The Scarlet Letter

Ⅰ about the Author and The Scarlet Letter

The scarlet letter was written by Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was an American novelist and short story writer. Between 1850 and 1860, he finished his four major romances, one of which was right The Scarlet Letter. What’s more, The Scarlet Letter was regarded as his most famous book. After it was published in 1850, it got an immediate and lasting success because of the way it addressed spiritual and moral issue from a uniquely American standpoint. And it was considered as one that initiated a distinctive American literary tradition.

The Scarlet Letter is made up of 24 chapters and a long prefatory called The Custom-House, telling how it came to write this book. It tells a story set in 17th-century Puritan Boston. The main character is Hester Prynne, who was determined and brave to go against the tradition. She committed adultery and gave birth to a girl when she thought that her husband had died. Because of this, she was forced to wear a scarlet “A” on her breast to remind her guilt and sin. However, she wore the scarlet “A” only to protect her lover. In fact, never had she 屈服 or thought herself was wrong. At last, her 坚强安东bravery to suffer all by herself touched her lover deeply .

Ⅱ Summary

One day in the 17th-century Boston, in front of a prison, a crowd of people gathered there, talking loudly. When the door opened, a young lady, called Hester Prynne came out with a 3-month-old baby in her arms. This little baby was her daughter, Pearl. And the young lady wearing a scarlet “A” on her breast was right the main character, Heater Prynne. She had to stand on the scaffold and be judged. She was forced to live far away with her daughter and wear the scarlet letter “A” all the time, which reminded her guilt. Right at this moment, Hester found an elder onlooker

in the crowd, who was in fact her husband. He was a doctor and much older than Hester. Two years ago, he sent her to Boston alone. Then it was said that he had died in the sea. During the 2 years when Hester waited for him, she fell in love with a minister there, called Dimmesdale. Because of Dimmesdale, Hester got to know what true love was and became brave to pursue real happiness. Though she was committed, in order to protect her lover, she was determined not to tell who he was and suffered all by herself.

However, Hester’s husband asked her to keep his true identity as a secret because he thought it was shameful. And now he worked as e doctor and called himself Roger Chillingworth. As little Pearl grew up day by day, the local community officials attempted to take her away from Hester, in order to give her a better education. Luckily, with the help of Dimmesdale, little Pearl could stay together with her mother. And because of this, Chillingworth began to suspect his relationship with Hester. As Dimmesdale was suffering from mysterious heart trouble, Chilingworth, as a doctor, got the chance to attach him in order to find more. One day, when Dimmesdale was sleeping, Chilingworth discovered a mark on his breast, which convinced that his suspicions were correct.

Chilingworth now was full of 仇恨 and decided to revenge. Soon seven years had passed, and little Pearl had grown into a willful, impish girl. And during the seven years, Hester now had won other’s respect because of her charitable deeds. The scarlet letter was no longer the sign of guilt and sin, but the sign of charity and humility. Meanwhile, Dimmesdale suffered more and more from his 自责One night, when Hester and Pearl were on the way home, they encountered Dimmesdale on the scaffold. He was weak, in low spirit and trying to punish himself for his sin. Then Hester and Pearl joined. Hester found that Dimmesdale was in a worsening condition. So she decided to ask Chilingworth to stop adding to Dimondale’s self-torment. But now he was full of and refused affirmly.

After Chilingworth’s refusal, Hester met with Dimmesdale in the forest secretly and told him Roger Chilingworth’s real identity. She was aware that Chilingworth had guessed that she would tell Dimmesdale the truth, so she suggested that Dimmesdale escape away with her, and then they could make a new family with Pearl. They decided to take a ship sailing in four days. Hester let down her beautiful hair and removed the scarlet letter out of a feeling of freedom and happpiness. The day before they left was a holiday, and Dimmesdale made his most eloquent sermon ever. However, Chilingworth had known their plan and decided to go together with them secretly. After Dimmesdale left the church and saw Hester and Pearl before the scaffold, he could not stand his deep 罪恶感 any longer. Then he got up onto the scaffold with Hester and Pearl, and confessed publicly. What’s more, he exposed the mark on his breast------a scarlet letter seared in to the flesh of his chest. He felt really released, and also came to the end of his life. As Pearl kissed him, Dimmesdale died.

Chilingworth was also frustrated after his revenge, and died a year later. Hester and Pearl then left together. However, many years later, Hester came back alone and wore the scarlet letter again. And later she received a letter, telling that Pearl got married to a European aristocrat. When Hester died, she was buried near his lover,

Dimmesdale. And they shared the same tombstone with a scarlet letter “A” on it. Ⅲ about the Theme

After reading The Scarlet Letter, the readers will raise a question: what is sin on earth? In my opinion,

Through this book, the writer led us to think about the theme of legalism, sin and guilt.

第二篇:Scarlet Letter 红字

Scarlet Letter

Born July 4, 1804, Nathaniel Hathorne was the only son of Captain Nathaniel Hathorne and Elizabeth Clarke Manning Hathorne. (Hawthorne added the ―w‖ to his name after he graduated from college.) Following the death of Captain Hathorne in 1808, Nathaniel, his mother, and his two sisters were forced to move in with Mrs. Hathorne‘s relatives, the Mannings. Here Nathaniel Hawthorn grew up in the company of women without a strong male role model; this environment may account for what biographers call his shyness and introverted personality.

This period of Hawthorne‘s life was mixed with the joys of reading and the resentment of financial dependence. While he studied at an early age with Joseph E. Worcester, a well-known lexicographer, he was not particularly fond of school. An injury allowed him to stay home for a year when he was nine, and his early ―friends‖ were books by Shakespeare, Spenser, Bunyan, and 18th century novelists.

During this time Mrs. Hathorne moved her family to land owned by the Mannings near Raymond, Maine. Nathaniel‘s fondest memories of these days were when ―I ran quite wild, and would, I doubt not, have willingly run wild till this time, fishing all day long, or shooting with an old fowling piece.‖ This idyllic life in the wilderness exerted its charm on the boy‘s imagination but ended in 1819 when he returned to Salem to prepare two years for college entrance.

Education

In 1821, Hawthorne entered Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. Among his classmates were Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow, who would become a distinguished poet and Harvard professor, and Franklin Pierce, future 14th president of the United States. Another classmate, Horatio Bridge, was later to offer a Boston publisher a guarantee against loss if he would publish Hawthorne‘s first collection of short stories.

Hawthorne graduated middle of his class in 1825. Regarding his aspirations, he wrote, ―I do not want to be a doctor and live by men‘s diseases, nor a minister to live by their sins, nor a lawyer to live by their quarrels. So, I don‘t see that there is anything left for me but to be an author.‖

His Early Career

For the next 12 years, Hawthorne lived in comparative isolation in an upstairs chamber at his mother‘s house, where he worked at perfecting his writing craft. He also began keeping notebooks or journals, a habit he continued throughout his life. He often jotted down ideas and descriptions, and his words are now a rich source of information about his themes, ideas, style experiments, and subjects.

In 1828, he published his first novel, Fanshaw: A Tale, at his own expense. Fanshaw was a short, imitation Gothic novel and poorly written. Dissatisfied with this novel, Hawthorne attempted to buy up all the copies so that no one could read it. He did not publish another novel for almost 25 years. By 1838, he had written two-thirds of the short stories he was to write in his lifetime. None of these stories gained him much attention, and he could not interest a publisher in printing a collection of his tales until 1837, when his college friend Horatio Bridge backed the publishing of Twice-Told Tales, a collection of Hawthorne‘s stories that had been published separately in magazines. His schoolmate and friend, Longfellow, reviewed the book with glowing terms. Edgar Allan Poe, known for his excoriating reviews of writers, not only wrote warmly of Hawthorne‘s book but also took the opportunity to define the short story in his now famous review. Twice-Told Tales is considered a masterpiece of literature, and it contains unmistakably American stories.

Financial Burdens and Marriage

In 1838, Hawthorne met Sophia Amelia Peabody, and the following year they were engaged. It was at this time that Hawthorne invested a thousand dollars of his meager capital in the Brook Farm Community at West Roxbury. There he became acquainted with Ralph Waldo Emerson and the naturalist Henry David Thoreau. These transcendentalist thinkers influenced much of Hawthorne‘s thinking about the importance of intuition rather than intellect in uncovering the truths of nature and human beings. Hawthorne left this experiment in November 1841, disillusioned with the viewpoint of the community, exhausted from the work, and without financial hope that he could support a wife. From this experience, however, he gained the setting for a later novel, The Blithedale Romance.

In a trip to Boston after leaving Brook Farm, Hawthorne reached an understanding about a salary for future contributions to the Democratic Review. He and Sophia married in Boston on July 9, 1842, and left for Concord, Massachusetts, where

-1-

they took up residence in the now-famous ―Old Manse.‖

Hawthorne‘s life at the ―Old Manse‖ was happy and productive, and these were some of the happiest years of his life. He was newly married, in love with his wife, and surrounded by many of the leading literary figures of the day: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and Bronson Alcott. During this time, Hawthorne wrote for the Democratic Review and produced some tales that would be published in 1846 in Mosses from an Old Manse.

Financial problems continued to plague the family, however. The birth of their first child, Una, caused Hawthorne to once again seek a financially secure job. With the help of his old friends, Hawthorne was appointed a surveyor for the port of Salem. His son, Julian, was born in 1846. Although the new job eased the financial problems for the family, Hawthorne again found little time to pursue his writing. Nevertheless, during this time, he was already forming ideas for a novel based on his Puritan ancestry and introduced by a preface about the Custom House where he worked. When the Whigs won the 1848 election, Hawthorne lost his position. It was a financial shock to the family, but it fortuitously provided him with time to write The Scarlet Letter.

The Golden Years of Writing

During these years Hawthorne was to write some of the greatest prose of his life. In 1849, Hawthorne wrote The Scarlet Letter, which won him much fame and greatly increased his reputation. While warmly received here and abroad, The Scarlet Letter sold only 8,000 copies in Hawthorne‘s lifetime.

In 1849, when the family moved to Lennox, Massachusetts, Hawthorne made the acquaintance of Herman Melville, a young writer who became a good friend. Hawthorne encouraged the young Melville, who later thanked him by dedicating his book, Moby Dick, to him. During this—the ―Little Red House‖ period in Lennox—Hawthorne wrote The House of the Seven Gables and some minor works that were published in 1851.

Around the time that Nathaniel and Sophia‘s second daughter, Rose, was born, the family moved to West Newton, where Hawthorne finished and published his novel about the Brook Farm experience, The Blithedale Romance, and also A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys. Because there was little to no literature published for children, Hawthorne‘s book was unique in this area.

Later Writing and Years Abroad

In Concord, the Hawthornes found a permanent house, along with nine acres of land, which they purchased from Bronson Alcott, the transcendentalist writer and father of Louisa May Alcott. Hawthorne renamed the house The Wayside, and in May, 1852, he and his family moved in. Here, Hawthorne was to write only two of his works: Tanglewood Tales, another collection designed for young readers, and A Life of Pierce, a campaign biography for his old friend from college. As a result of the biography, President Pierce awarded Hawthorne with an appointment as United States consul in Liverpool, England. The Hawthornes spent the next seven years in Europe.

Although Hawthorne wrote no additional fiction while serving as consul, he kept a journal that later served as a source of material for Our Old Home, a collection of sketches dealing with English scenery, life, and manners published in 1863. While in Italy, Hawthorne kept a notebook that provided material for his final, complete work of fiction, which was published in England as Transformation and, in America, as The Marble Faun.

By the autumn of 1863, Hawthorne was a sick man. In May, 1864, he traveled to New Hampshire with his old classmate Pierce in search of improved health. During this trip, he died in his sleep on May 19, 1864, in Plymouth, New Hampshire. He was buried in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery at Concord. Widely eulogized as one of America‘s foremost writers, his fellow authors gathered to show their respect. Among his pallbearers were Longfellow, Holmes, Lowell, and Emerson. Today he rests there with Washington Irving, Emerson, Thoreau, and the Alcotts, as well as his wife, Sophia.

INTRODUCTION

―The life of the Custom House lies like a dream behind me …. Soon, likewise, my old native town will loom upon me

through the haze of memory, a mist brooding over and around it; as if it were no portion of the real earth, but an overgrown village in cloud-land, with only imaginary inhabitants to people its wooden houses, and walk its homely lanes, and the unpicturesque prolixity of its main street … It may be, however,—oh, transporting and triumphant thought!—that the great-grandchildren of the present race may sometimes think kindly of the scribbler of bygone days ….‖

In the mid-1800s when Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote these words in the Custom House preface to The Scarlet Letter, he

-2-

could not have imagined the millions of readers a century later who would ―think kindly of the scribbler of bygone days‖ and continue to make his novel a best-seller. The mist of imagination that falls over Salem, Massachusetts, in his

description is the same aura that permeates the setting of his novel. Look for the Boston of 1640 in history books, and you will not find the magical and Gothic elements that abound in Hawthorne‘s story. For the mind of genius has created a

Boston that is shrouded in darkness and mystery and surrounded by a forest of sunshine and shadow. In writing The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne was creating a form of fiction he called the psychological romance, and woven throughout his novel are elements of Gothic literature. What he created would later be followed by other romances, but never would they attain the number of readers or the critical acclaim of The Scarlet Letter.

Hawthorne began The Scarlet Letter in September, 1849, and finished it, amazingly, in February, 1850. Its publication made his literary reputation and temporarily eased some of his financial burdens. This novel was the culmination of

Hawthorne‘s own reading, study, and experimentation with themes about the subjects of Puritans, sin, guilt, and the human conflict between emotions and intellect. Since its first publishing in March of 1850, The Scarlet Letter has never been out of print. Even today, Hawthorne‘s romance is one of the best-selling books on the market. Perhaps The Scarlet Letter is so popular, generation after generation, because its beauty lies in the layers of meaning and the uncertainties and ambiguities of the symbols and characters. Each generation can interpret it and see relevance in its subtle meanings and appreciate the genius lying behind what many critics call ―the perfect book.‖

An interest in the past was not new to Hawthorne. As a boy, he had read novelists, such as James Fenimore Cooper and Sir Walter Scott, who wrote historical romances. Although the past appeared an appropriate subject for romance, Hawthorne wanted to go beyond the shallow characters of his predecessors‘ books and create what he called a ―psychological

romance‖—one that would contain all the conventional techniques of romance but add deep, probing portraits of human beings in conflict with themselves.

Complementing this intriguing theory of a new type of romance, Hawthorne‘s writing prior to 1850 hinted at the

masterpiece yet to come. In ―The Gentle Boy,‖ he wrote of an emotional creature faced with the hostility of Puritans, who did not understand emotions. The ambiguity of sin was the subject of still another story, ―Young Goodman Brown.‖ These stories helped Hawthorne develop some of the themes that would become part of The Scarlet Letter. Two other stories that would predate the conflict of head and heart in his novel were ―Rappaccini‘s Daughter‖ and ―The Birthmark.‖ The cold intellect of Chillingworth, man of science, can be seen in the earlier conflict of these two stories. Both concern men of science or cold intellect who lack human sympathy and compassion and so sacrifice loved ones. This idea was further developed in ―Ethan Brand,‖ a study in the conflict of head and heart. In this story, Hawthorne defined the unpardonable sin as the domination of intellect over emotion. He was to develop this idea in The Scarlet Letter with his portrayal of Chillingworth, the husband who seeks revenge.

In The Scarlet Letter, the reader should be prepared to meet the real and the unreal, the actual and the imaginary, the probable and the improbable, all seen in the moonlight with the warmer light of a coal fire changing their hues. What is Truth and what is Imagination? This is the Boston of the Puritans: Bible-reading, rule making, judgment framing.

Surrounding it is the forest of the Devil, dark, shadowy, momentarily filled with sunlight, but always the home of those

who would break the rules and those who listen to their passions. Enter this setting with Hawthorne and ample imagination, and the reader will find a story difficult to forget.

A Brief Synopsis

In June 1642, in the Puritan town of Boston, a crowd gathers to witness an official punishment. A young woman, Hester Prynne, has been found guilty of adultery and must wear a scarlet A on her dress as a sign of shame. Furthermore, she must stand on the scaffold for three hours, exposed to public humiliation. As Hester approaches the scaffold, many of the women in the crowd are angered by her beauty and quiet dignity. When demanded and cajoled to name the father of her child, Hester refuses.

As Hester looks out over the crowd, she notices a small, misshapen man and recognizes him as her long-lost husband, who has been presumed lost at sea. When the husband sees Hester‘s shame, he asks a man in the crowd about her and is told the story of his wife‘s adultery. He angrily exclaims that the child‘s father, the partner in the adulterous act, should also be punished and vows to find the man. He chooses a new name—Roger Chillingworth—to aid him in his plan.

-3-

Reverend John Wilson and the minister of her church, Arthur Dimmesdale, question Hester, but she refuses to name her lover. After she returns to her prison cell, the jailer brings in Roger Chillingworth, a physician, to calm Hester and her child with his roots and herbs. Dismissing the jailer, Chillingworth first treats Pearl, Hester‘s baby, and then demands to know the name of the child‘s father. When Hester refuses, he insists that she never reveal that he is her husband. If she ever does so, he warns her, he will destroy the child‘s father. Hester agrees to Chillingworth‘s terms even though she suspects she will regret it.

Following her release from prison, Hester settles in a cottage at the edge of town and earns a meager living with her

needlework. She lives a quiet, somber life with her daughter, Pearl. She is troubled by her daughter‘s unusual character. As an infant, Pearl is fascinated by the scarlet A. As she grows older, Pearl becomes capricious and unruly. Her conduct starts rumors, and, not surprisingly, the church members suggest Pearl be taken away from Hester.

Hester, hearing the rumors that she may lose Pearl, goes to speak to Governor Bellingham. With him are Reverends Wilson and Dimmesdale. When Wilson questions Pearl about her catechism, she refuses to answer, even though she knows the correct response, thus jeopardizing her guardianship. Hester appeals to Reverend Dimmesdale in desperation, and the minister persuades the governor to let Pearl remain in Hester‘s care.

Because Reverend Dimmesdale‘s health has begun to fail, the townspeople are happy to have Chillingworth, a newly arrived physician, take up lodgings with their beloved minister. Being in such close contact with Dimmesdale,

Chillingworth begins to suspect that the minister‘s illness is the result of some unconfessed guilt. He applies psychological pressure to the minister because he suspects Dimmesdale to be Pearl‘s father. One evening, pulling the sleeping

Dimmesdale‘s vestment aside, Chillingworth sees something startling on the sleeping minister‘s pale chest: a scarlet A. Tormented by his guilty conscience, Dimmesdale goes to the square where Hester was punished years earlier. Climbing the scaffold, he sees Hester and Pearl and calls to them to join him. He admits his guilt to them but cannot find the courage to do so publicly. Suddenly Dimmesdale sees a meteor forming what appears to be a gigantic A in the sky; simultaneously, Pearl points toward the shadowy figure of Roger Chillingworth. Hester, shocked by Dimmesdale‘s deterioration, decides to obtain a release from her vow of silence to her husband. In her discussion of this with Chillingworth, she tells him his obsession with revenge must be stopped in order to save his own soul.

Several days later, Hester meets Dimmesdale in the forest, where she removes the scarlet letter from her dress and

identifies her husband and his desire for revenge. In this conversation, she convinces Dimmesdale to leave Boston in secret on a ship to Europe where they can start life anew. Renewed by this plan, the minister seems to gain new energy. Pearl, however, refuses to acknowledge either of them until Hester replaces her symbol of shame on her dress.

Returning to town, Dimmesdale loses heart in their plan: He has become a changed man and knows he is dying.

Meanwhile, Hester is informed by the captain of the ship on which she arranged passage that Roger Chillingworth will also be a passenger.

On Election Day, Dimmesdale gives what is declared to be one of his most inspired sermons. But as the procession leaves the church, Dimmesdale stumbles and almost falls. Seeing Hester and Pearl in the crowd watching the parade, he climbs upon the scaffold and confesses his sin, dying in Hester‘s arms. Later, witnesses swear that they saw a stigma in the form of a scarlet A upon his chest. Chillingworth, losing his revenge, dies shortly thereafter and leaves Pearl a great deal of money, enabling her to go to Europe with her mother and make a wealthy marriage.

Several years later, Hester returns to Boston, resumes wearing the scarlet letter, and becomes a person to whom other women turn for solace. When she dies, she is buried near the grave of Dimmesdale, and they share a simple slate tombstone with the inscription ―On a field, sable, the letter A gules.‖

List of Characters

Hester Prynne A young woman sent to the colonies by her husband, who plans to join her later but is presumed lost at sea. She is a symbol of the acknowledged sinner; one whose transgression has been identified and who makes appropriate, socio-religious atonement.

Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale Dimmesdale is the unmarried pastor of Hester's congregation; he is also the father of Hester's daughter, Pearl. He is a symbol of the secret sinner; one who recognizes his transgression but keeps it hidden and secret, even to his own downfall.

-4-

Pearl Pearl is the illegitimate daughter of Hester Prynne and Arthur Dimmesdale. She is the living manifestation of Hester's sin and a symbol of the product of the act of adultery and of an act of passion and love.

Roger Chillingworth The pseudonym assumed by Hester Prynne's aged scholar-husband. He is a symbol of evil, of the ―devil‘s handyman,‖ of one consumed with revenge and devoid of compassion.

Governor Bellingham This actual historical figure, Richard Bellingham, was elected governor in 1641, 1654, and 1665. In The Scarlet Letter, he witnesses Hester's punishment and is a symbol of civil authority and, combined with John Wilson, of the Puritan Theocracy.

Mistress Hibbins Another historical figure, Ann Hibbins, sister of Governor Bellingham, was executed for witchcraft in 1656. In the novel, she has insight into the sins of both Hester and Dimmesdale and is a symbol of super or preternatural knowledge and evil powers.

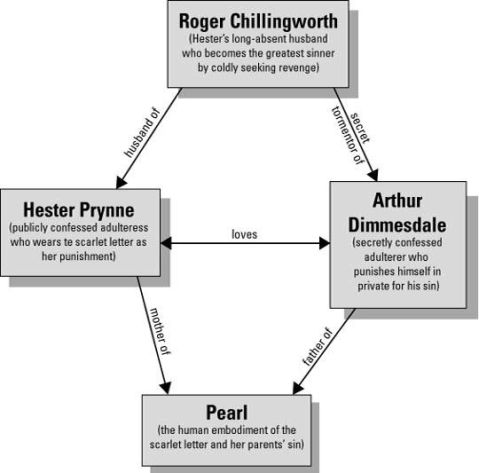

John Wilson The historical figure on whom this character is based was an English-born minister who arrived in Boston in 1630. He is a symbol of religious authority and, combined with Governor Bellingham, of the Puritan Theocracy. Character Map

Summaries and Commentaries

The Custom House

Hawthorne begins The Scarlet Letter with a long introductory essay that generally functions as a preface but, more specifically, accomplishes four significant goals: outlines autobiographical information about the author, describes the conflict between the artistic impulse and the commercial environment, defines the romance novel (which Hawthorne is credited with refining and mastering), and authenticates the basis of the novel by explaining that he had discovered in the Salem Custom House the faded scarlet A and the parchment sheets that contained the historical manuscript on which the novel is based.

The preface sets the atmosphere of the story and connects the present with the past. Hawthorne‘s description of the Salem port of the 1800s is directly related to the past history of the area. The Puritans who first settled in Massachusetts in the 1600s founded a colony that concentrated on God‘s teachings and their mission to live by His word. But this philosophy was eventually swallowed up by the commercialism and financial interests of the 1700s.

-5-

The clashing of the past and present is further explored in the character of the old General. The old General‘s heroic

qualities include a distinguished name, perseverance, integrity, compassion, and moral inner strength. He is ―the soul and spirit of New England hardihood.‖ Now put out to pasture, he sometimes presides over the Custom House run by corrupt public servants, who skip work to sleep, allow or overlook smuggling, and are supervised by an inspector with ―no power of thought, nor depth of feeling, no troublesome sensibilities,‖ who is honest enough but without a spiritual compass.

A further connection to the past is his discussion of his ancestors. Hawthorne has ambivalent feelings about their role in his life. In his autobiographical sketch, Hawthorne describes his ancestors as ―dim and dusky,‖ ―grave, bearded, sable-cloaked, and steel crowned,‖ ―bitter persecutors‖ whose ―better deeds‖ will be diminished by their bad ones. There can be little doubt of Hawthorne‘s disdain for the stern morality and rigidity of the Puritans, and he imagines his predecessors‘

disdainful view of him: unsuccessful in their eyes, worthless and disgraceful. ―A writer of story books!‖ But even as he disagrees with his ancestor‘s viewpoint, he also feels an instinctual connection to them and, more importantly, a ―sense of place‖ in Salem. Their blood remains in his veins, but their intolerance and lack of humanity becomes the subject of his novel.

This ambivalence in his thoughts about his ancestors and his hometown is paralleled by his struggle with the need to

exercise his artistic talent and the reality of supporting a family. Hawthorne wrote to his sister Elizabeth in 1820, ―No man can be a Poet and a Bookkeeper at the same time.‖ Hawthorne‘s references to Emerson, Thoreau, Channing, and other romantic authors describe an intellectual life he longs to regain. His job at the Custom House stifles his creativity and imagination. The scarlet letter touches his soul (he actually feels heat radiate from it), and while ―the reader may smile,‖ Hawthorne feels a tugging that haunts him like his ancestors.

In this preface, Hawthorne also shares his definition of the romance novel as he attempts to imagine Hester Prynne‘s story beyond Pue‘s manuscript account. A careful reading of this section explains the author‘s use of light (chiaroscuro) and setting as romance techniques in developing his themes. Hawthorne explains that, in a certain light and time and place, objects ―… seem to lose their actual substance, and become things of intellect.‖ He asserts that, at the right time with the right scene before him, the romance writer can ―dream strange things and make them look like truth.‖

Finally, the preface serves as means of authenticating the novel by explaining that Hawthorne had discovered in the Salem Custom House the faded scarlet A and the parchment sheets that contained the historical manuscript on which the novel is based. However, we know of no serious, scholarly work that suggests Hawthorne was ever actually in possession of the letter or the manuscript. This technique, typical of the narrative conventions of his time, serves as a way of giving his story an air of historic truth. Furthermore, Hawthorne, in his story, ―Endicott and the Red Cross,‖ published nine years before he took his Custom House position, described the incident of a woman who, like Hester Prynne, was forced to wear a letter A on her breast.

Chapter 1

In this first chapter, Hawthorne sets the scene of the novel—Boston of the seventeenth century. It is June, and a throng of drably dressed Puritans stands before a weather-beaten wooden prison. In front of the prison stands an unsightly plot of weeds, and beside it grows a wild rosebush, which seems out of place in this scene dominated by dark colors.

In this chapter, Hawthorne sets the mood for the ―tale of human frailty and sorrow‖ that is to follow. His first paragraph introduces the reader to what some might want to consider a (or the) major character of the work: the Puritan society. What happens to each of the major characters—Hester, Pearl, Dimmesdale, and Chillingworth—results from the collective ethics, morals, psyche, and unwavering sternness and rigidity of the individual Puritans, whom Hawthorne introduces figuratively in this chapter and literally and individually in the next.

Dominating this chapter are the decay and ugliness of the physical setting, which symbolize the Puritan society and culture and foreshadow the gloom of the novel. The two landmarks mentioned, the prison and the cemetery, point not only to the ―practical necessities‖ of the society, but also to the images of punishment and providence that dominate this culture and permeate the entire story.

The rosebush, its beauty a striking contrast to all that surrounds it—as later the beautifully embroidered scarlet A will be—is held out in part as an invitation to find ―some sweet moral blossom‖ in the ensuing, tragic tale and in part as an image that ―the deep heart of nature‖ (perhaps God) may look more kindly on the errant Hester and her child (the roses

-6-

among the weeds) than do her Puritan neighbors. Throughout the work, the nature images contrast with the stark darkness of the Puritans and their systems.

Hawthorne makes special note that this colony earlier set aside land for both a cemetery and a prison, a sign that all

societies, regardless of their good intentions, eventually succumb to the realities of man‘s nature (sinful/punishment/prison) and destiny (mortal/death/cemetery). In those societies in which the church and state are the same, when man breaks the law, he also sins. From Adam and Eve on, man‘s inability to obey the rules of the society has been his downfall.

The Puritan society is symbolized in the first chapter by the plot of weeds growing so profusely in front of the prison. Nevertheless, nature also includes things of beauty, represented by the wild rosebush. The rosebush is a strong image developed by Hawthorne which, to the sophisticated reader, may sum up the whole work. First it is wild; that is, it is of nature, God given, or springing from the ―footsteps of the sainted Anne Hutchinson.‖ Second, according to the author, it is beautiful—offering ―fragrant and fragile beauty to the prisoner‖—in a field of ―unsightly vegetation.‖ Third, it is a ―token that the deep heart of Nature could pity and be kind to‖ the prisoner entering the structure or the ―condemned criminal as he came forth to his doom.‖ Finally, it is a predominant image throughout the romance. Much the same sort of descriptive analyses that can be written about the rosebush could be ascribed to the scarlet letter itself or to little Pearl or, perhaps, even to the act of love that produced them both.

Finally, the author points toward many of the images that are significant to an understanding of the novel. In this instance, he names the chapter ―The Prison Door.‖ The reader needs to pay particular attention to the significance of the prison

generally and the prison door specifically. The descriptive language in reference to the prison door—― … heavily timbered with oak, and studded with iron spikes‖ and the ―rust on the ponderous iron-work … looked more antique than anything else in the New World‖ and, again, ― … seemed never to have known a youthful era‖—foreshadows and sets the tone for the tale that follows.

Glossary

Cornhill part of Washington Street. Now part of City Hall Plaza.

Isaac Johnson a settler (1601-1630) who left land to Boston; he died shortly after the Puritans arrived. His land would be north of King‘s Chapel (1688), which can be visited today.

burdock any of several plants with large basal leaves and purple-flowered heads covered with hooked prickles.

pigweed any of several coarse weeds with dense, bristly clusters of small green flowers. Also called lamb‘s quarters. apple-peru a plant that is part of the nightshade family; poisonous.

portal here, the prison door.

Anne Hutchinson a religious dissenter (1591-1643). In the 1630s she was excommunicated by the Puritans and exiled from Boston and moved to Rhode Island.

Chapter 2

The Puritan women waiting outside the prison self-righteously and viciously discuss Hester Prynne and her sin. Hester, proud and beautiful, emerges from the prison. She wears an elaborately embroidered scarlet letter A—standing for ―adultery‖—on her breast, and she carries a three-month-old infant in her arms.

Hester is led through the unsympathetic crowd to the scaffold of the pillory. Standing alone on the scaffold as punishment for her adulterous behavior, she remembers her past life in England and on the European continent. Suddenly becoming aware of the stern faces looking up at her, Hester painfully realizes her present position of shame and punishment. Although the reader actually meets only Hester and her infant daughter, Pearl, in this chapter, Hawthorne begins his characterization of all four of the novel‘s major characters. He describes Hester physically, and he tells about her

background, illustrating her pride and shame. Then we see Pearl and hear her cry out when her mother fiercely clutches her at the end of the chapter. Although Pearl is one of the physical symbols of Hester's sin (the other is the scarlet A), she is much more than that. She is the product of an act of love—socially forbidden love as it may have been—but love still. This is why Pearl, as we later learn, is not amenable to social rules. She was conceived in an act that was intolerable in the Puritan code and society.

In addition to Hester and Pearl‘s appearance, we get our first glimpse of the Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale and Roger Chillingworth, the novel‘s other two main characters. Although the irony of Dimmesdale's relationship to Hester is not yet

-7-

apparent, his grief over his parishioner Hester is commented on by one of the women assembled near the prison who notes that Dimmesdale ―takes it very grievously to heart that such a scandal should have come upon his congregation.‖ And, although Roger Chillingworth is not yet named, we are given a rather full characterization of the man through Hester's recollections of him. He is the ―misshapen scholar‖ who is Hester's legal husband.

Chapter 2 also contains a description of the Puritan society and reveals Hawthorne's critical attitude toward it. The smugly pious attitude of the women assembled in front of the prison who condemn Hester is frightening—especially when we hear them suggest that Hester should be scalded with a hot iron applied to her forehead to mark her as a ―hussy,‖ an immoral woman. Although this scene vividly dramatizes what Hawthorne found objectionable about early American Puritanism, he avoids over-generalizing here by including the comments of a good-hearted young wife to show that not all Puritan women were as bitter and pugnaciously pious as these ―gossips.‖ The young woman‘s soft remarks of sympathy for Hester's

suffering contrast sharply with the comments of the majority of the women. It is important to note, however, that even this young mother has brought her child to witness the punishment, passing these morals and behaviors to the next generation. When Hester appears with Pearl, she is in stark contrast to the gloom and the grim reality of the crowd. She has a natural grace and dignity and rejects the arm of the beadle, walking into the sunlight on her own. The most startling part of her appearance is the scarlet letter A on her dress. What is meant to be a badge of shame is elaborately decorated in threads of gold. It goes far beyond the standards of richness—sumptuary laws—decreed by the colony. Her extraordinary appearance defies the order of the governor and the ministers. The scarlet letter is ―fantastically embroidered and illuminated‖ and takes ―her out of the ordinary relations with humanity‖ and into a sphere all her own. The red of the letter, standing for adultery, reminds the reader of the rosebush and the letter that later appears in the sky. Its color, for now at least, is associated with her sin and will be strongly connected to Pearl throughout the novel.

Stylistically, the chapter employs a somewhat heavy historical narrative, occasionally interrupted by Hawthorne's comments. It also uses such symbols as the beadle, the scarlet letter A, and Pearl. In fact, many of the novel‘s themes

become apparent by investigating the images and symbols represented in the characters, physical objects, and larger social issues. For example, the beadle, or town crier, who carries a sword and walks with a staff symbolic of religious—and therefore social—authority, is described as ―grim and grisly.‖ This description also characterizes , both the atmosphere in Chapter 2 and, more important, the society of which the beadle is a part. As the novel progresses, Pearl, the offspring of Hester‘s adulterous affair, becomes more strongly linked to the scarlet letter A that Hester wears on her clothing; likewise, both Pearl‘s and the A‘s symbolism are also more fully developed.

Glossary

physiognomies facial features and expression, esp. as supposedly indicative of character

Antinomian a believer in the Christian doctrine that faith alone, not obedience to the moral law, is necessary for salvation; to the Puritans, the Antinomian doctrine is heretical.

heterodox religious person who disagrees with church beliefs; unorthodox.

petticoat and farthingale underskirts and hoops beneath them.

the man-like Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth I of England (1558-1603), characterized as having masculine qualities. gossip a person who chatters or repeats idle talk and rumors

beadle a minor parish officer who keeps order in church.

ignominy shame and dishonor; infamy.

rheumatic flannel material worn to keep warm, especially to ease the pain of rheumatism in the joints.

an hour past meridian 1:00 p.m.

pillory stocks where petty offenders were formerly locked and exposed to public scorn.

Papist a Roman Catholic; the Puritans thought them to be heretics.

spectral of, having the nature of, or like a specter; phantom; ghostly; supernatural.

phantasmagoric dreamlike; fantastic.

Elizabethan ruff an elaborate collar worn around the neck, consisting of tiny accordion pleats.

Chapter 3

Hester recognizes a small, rather deformed man standing on the outskirts of the crowd and clutches Pearl fiercely to her

-8-

bosom. Meanwhile, the man, a stranger to Boston, recognizes Hester and is horror-struck.

Inquiring, the man learns of Hester‘s history, her crime (adultery), and her sentence: to stand on the scaffold for three hours and to wear the symbolic letter A for the rest of her life. The stranger also learns that Hester refuses to name the man with whom she had the sexual affair. This knowledge greatly upsets him, and he vows that Hester‘s unnamed partner ―will be known!—he will be known!—he will be known!‖

The Reverend Mr. Dimmesdale, visibly upset, pleads with Hester to name her accomplice. He tells her that she should name her partner in sin because perhaps the man doesn‘t have the courage to step forward even if he wants to. Yet despite Dimmesdale's passionate appeal, followed by harsher demands from the Reverend Mr. Wilson and from a stern voice in the crowd (presumably that of the deformed stranger), Hester steadfastly refuses to name the father of her child. After a long and tedious sermon by the Reverend Mr. Wilson, during which Hester tries ineffectively to quiet Pearl‘s crying, she is led back to prison.

The novel‘s other two principal characters now make their first physical appearance, and the tensions of the story begin to develop. In Chapter 4, the reader learns that the stranger who so terrifies Hester calls himself Roger Chillingworth, a

pseudonym he has chosen for himself. In reality, he is Roger Prynne, the husband whom Hester fears meeting face to face. The other principal character is the young Reverend Dimmesdale, who pleads with Hester to name the father of her infant daughter; Dimmesdale is Pearl‘s father.

Hawthorne‘s portrayal of Chillingworth emphasizes his physical deformity. More important, Chillingworth‘s misshapen body reflects (or symbolizes) the evil in his soul, which builds as the novel progresses. In this chapter, Hawthorne provides hints of just how obsessed Chillingworth will become with punishing Dimmesdale. For example, when Chillingworth recognizes Hester standing alone on the scaffold, ―a writhing horror twisted itself across his features, like a snake gliding swiftly over them ….‖ Characteristic of Chillingworth, he internalizes ―into the depths of his nature‖ this external

convulsion, which will feed his appetite for revenge throughout the novel. The image of the snake is apt when we recall the serpent in the biblical Garden of Eden and the carnal knowledge that it represents. From this chapter forward, revenge and punishment for Dimmesdale will be Chillingworth‘s only consuming passion.

Dimmesdale‘s one-paragraph speech to Hester reveals more about his character than any description of his physical body and nervous habits that Hawthorne provides. Knowing that he was Hester‘s sexual partner and is Pearl‘s father, the speech that he gives is ripe with double meanings. On one level, he gives a public chastisement of Hester for not naming her lover; on another level, he makes a personal plea to her to name him as her lover and Pearl‘s father because he is too morally weak to do so himself. Ironically, what is initially intended to be a speech about Hester becomes more a commentary about his own sinful behavior.

In his speech, Dimmesdale asks Hester to recognize his ―accountability‖ in addressing her, and he begs her to do what he cannot do himself. Publicly, he is her spiritual leader, and, as such, he is responsible for her moral behavior. Privately, however, he was her lover, and he shares the blame of the horrible situation that she is in. He then admonishes her, as her spiritual leader, to name her accomplice so that her soul might find peace on earth and, more important, so that she might better her chance for salvation after her death. When he then goes on to ―charge‖ her with naming the transgressor, we understand that he is privately pleading with her to expose him publicly and thereby help ensure his salvation, for without public repentance salvation is not attainable.

The dichotomy between Dimmesdale‘s public speech and personal meaning is most evident in the phrase ―believe me.‖ This phrase comes directly following his plea that Hester not take into consideration any feelings she might still have for him. It also follows acknowledgment—privately to himself, but through public speech—that it would be better for him to step down ―from a high place‖ and publicly stand beside her on the scaffold. Ultimately, his official, public duty and his private, personal intention are one and the same: to admonish Hester to expose her lover‘s—his own—immorality because he is too morally weak to do so himself.

Glossary

Daniel a prophet from the Old Testament.

Governor Bellingham (1592-1672) the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony.

halberds combination battle-axes and spears used in the 15th and 16th centuries.

-9-

skull-cap a light, closefitting, brimless cap, usually worn indoors.

Chapter 4

Back in her prison cell, Hester is in a state of nervous frenzy, and Pearl writhes in painful convulsions. That evening, when Roger Chillingworth enters Hester's prison cell, she fears his intentions, but he gives Pearl a draught of medicine that eases the child‘s pain almost immediately, and she falls asleep. After he persuades Hester to drink a sedative to calm her frayed nerves, the two sit and talk intimately and sympathetically, each of them accepting a measure of blame for Hester's adulterous affair.

Chillingworth, the injured husband, seeks no revenge against Hester, but he is determined to discover the father of Pearl. Although this unidentified man doesn‘t wear a scarlet A on his clothes as Hester does, Chillingworth vows that he will ―read it on his heart.‖ He then makes Hester promise not to reveal his identity. Hester takes an oath to keep Chillingworth's identity a secret, although she expresses the fear that her vow of silence may prove the ruin of her soul.

Unlike the previous chapter, Hawthorne does not summarize or discuss the actions of his characters, nor does he tell the readers what to think. Instead, he puts Hester and Chillingworth together and lets the reader learn about their attitudes and their relationship to each other through their dialogue. By juxtaposing heavily prosaic chapters, like Chapter 3, with ones dominated by the characters‘ dialogue, Hawthorne creates a pattern in the novel that heightens the dramatic content of the dialogic chapters.

Chapter 4 is especially important to understanding Chillingworth. Hawthorne gives a view of what he has been as well as what he is to become. Throughout the novel, he is referred to as a scholar, a man most interested in studying—reading about—human behavior. Unfortunately, however, Chillingworth hints that in his pursuit of scholarship, he has failed both Hester and himself. He admits to her, ―I betrayed thy budding youth into a false and unnatural relation with my decay.‖ We can initially sympathize with this lonely scholar who has been robbed of his wife, but we also can see the element of his future self-destruction in his grim determination to discover the man who has offended him. In fact, as Hester and

Chillingworth continue their conversation, we see the development of Chillingworth as one of the novel‘s symbols of evil. Of Hester, we learn that she has never pretended to love her husband but that she deeply loves the man whom

Chillingworth has vowed to punish. Ironically, it is Hester's concern for Dimmesdale, more than her sense of obligation to her marriage, that persuades her to promise never to reveal that Chillingworth is her husband. This promise will make both Hester and Dimmesdale suffer greatly later in the book.

Glossary

Indian sagamores chiefs or subchiefs in the Abnakis culture.

stripes [Archaic] welts on the skin caused by whipping.

alchemy the ancient system of chemistry and philosophy having the aim of changing base metals into gold.

simples [Archaic] medicines from herbs or plants.

leech .[Archaic] a doctor. In Hawthorne's time, blood-sucking leeches were used to effect a cure by removing blood. Lethe the river of forgetfulness, flowing through Hades, whose water produces loss of memory in those who drink of it. Nepenthe a drug supposed by the ancient Greeks to cause forgetfulness of sorrow.

Paracelsus (1493-1541) The most famous medieval alchemist; he was Swiss.

bale-fire an outdoor fire; bonfire; here, a beacon fire.

Black Man the devil who ―haunts the forest.‖

Chapter 5

Her term of imprisonment over, Hester is now free to go anywhere in the world, yet she does not leave Boston; instead, she chooses to move into a small, seaside cottage on the outskirts of town. She supports herself and Pearl through her skill as a seamstress. Her work is in great demand for clothing worn at official ceremonies and among the fashionable women of the town—for every occasion except a wedding.

Despite the popularity of her sewing, however, Hester is a social outcast. The target of vicious abuse by the community, she endures the abuse patiently. Ironically, she begins to believe that the scarlet A allows her to sense sinful and immoral feelings in other people.

Chapter 5 serves the purposes of filling in background information about Hester and Pearl and beginning the development

-10-

of Hester and the scarlet as two of the major symbols of the romance. By positioning Hester‘s cottage between the town and the wilderness, physically isolated from the community, the author confirms and builds the image of her that was portrayed in the first scaffold scene—that of an outcast of society being punished for her sin/crime and as a product of nature. Society views her ― … as the figure, the body, the reality of sin.‖

Despite Hester's apparent humility and her refusal to strike back at the community, she resents and inwardly rebels against the viciousness of her Puritan persecutors. She becomes a living symbol of sin to the townspeople, who view her not as an individual but as the embodiment of evil in the world. Twice in this chapter, Hawthorne alludes to the community‘s using Hester‘s errant behavior as a testament of immorality. For moralists, she represents woman‘s frailty and sinful passion, and when she attends church, she is often the subject of the preacher‘s sermon.

Banished by society to live her life forever as an outcast, Hester‘s skill in needlework is nevertheless in great demand. Hawthorne derisively condemns Boston‘s Puritan citizens throughout the novel, but here in Chapter 5 his criticism is especially sharp. The very community members most appalled by Hester‘s past conduct favor her sewing skills, but they deem their demand for her work almost as charity, as if they are doing her the favor in having her sew garments for them. Their small-minded and contemptuous attitudes are best exemplified in their refusal to allow Hester to sew garments for weddings, as if she would contaminate the sacredness of marriage were she to do so.

The irony between the townspeople‘s condemnation of Hester and her providing garments for them is even greater when we learn that Hester is not overly proud of her work. Although Hester has what Hawthorne terms ―a taste for the gorgeously beautiful,‖ she rejects ornamentation as a sin. We must remember that Hester, no matter how much she

inwardly rebels against the hypocrisy of Puritan society, still conforms to the moral strictness associated with Puritanism. The theme of public and private disclosure that so greatly marked Dimmesdale‘s speech in Chapter 3 is again present in this chapter, but this time the scarlet A on Hester‘s clothing is associated with the theme. Whereas publicly the letter inflicts scorn on Hester, it also endows her with a new, private sense of others‘ own sinful thoughts and behavior; she gains a ―sympathetic knowledge of the hidden sin in other hearts.‖ The scarlet letter—what it represents—separates Hester from society, but it enables her to recognize sin in the very same society that banishes her. Hawthorne uses this dichotomy to point out the hypocritical nature of Puritanism: Those who condemn Hester are themselves condemnable according to their own set of values. Similar to Hester‘s becoming a living symbol of immoral behavior, the scarlet A becomes an object with a life seemingly its own: Whenever Hester is in the presence of a person who is masking a personal sin, ―the red infamy upon her breast would give a sympathetic throb.‖

In the Custom House preface, Hawthorne describes his penchant for mixing fantasy with fact, and this technique is evident in his treatment of the scarlet A. In physical terms, this emblem is only so much fabric and thread. But Hawthorne‘s use of the symbol at various points in the story adds a dimension of fantasy to factual description. In the Custom House,

Hawthorne claims to have ―experienced a sensation … as if the letter were not of red cloth, but red-hot iron.‖ Similarly, here in Chapter 5, he suggests that, at least according to some townspeople, the scarlet A literally sears Hester‘s chest and that, ―red-hot with infernal fire,‖ it glows in the dark at night. These accounts create doubt in the reader‘s mind regarding the true nature and function of the symbol. Hawthornes‘ imbuing the scarlet A with characteristics that are both fantastical and symbolic is evident throughout the novel—particularly when Chillingworth sees a scarlet A emblazoned on Dimmesdale‘s bare chest and when townspeople see a giant scarlet A in the sky—and is a technique common to the romance genre.

Glossary

ordinations regulations, laws.

sumptuary laws laws set up by the colony concerning expenses for personal items like clothing.

plebeian order the commoners.

emolument profit that comes from employment or political office.

a rich, voluptuous, Oriental characteristic the gorgeous, exquisite, exotically beautiful.

contumaciously disobedient stubbornly resisting authority.

talisman anything thought to have magic power; a charm.

Chapter 6

-11-

During her first three years, Pearl, who is so named because she came ―of great price,‖ grows into a physically beautiful, vigorous, and graceful little girl. She is radiant in the rich and elaborate dresses that Hester sews for her. Inwardly, however, Pearl possesses a complex character. She shows an unusual depth of mind, coupled with a fiery passion that Hester is

incapable of controlling either with kindness or threats. Pearl shows a love of mischief and a disrespect for authority, which frequently reminds Hester of her own sin of passion.

Because both Hester and Pearl are excluded from society, they are constant companions. When Pearl is on walks with her mother, she occasionally finds herself surrounded by the curious children of the village. Rather than attempt to make friends with them, she pelts them with stones and violent words.

Pearl's only companion in her playtime is her imagination. Significantly, in her games of make-believe, she never creates friends; she creates only enemies—Puritans whom she pretends to destroy. But the object that most captures her

imagination is the scarlet letter A on her mother's clothing. Hester worries that Pearl is possessed by a fiend, an impression strengthened when Pearl denies having a Heavenly Father and then laughingly demands that Hester tell her where she came from.

This chapter develops Pearl both as a character and as a symbol. Pearl is a mischievous and almost unworldly child, whose uncontrollable nature reflects the sinful passion that led to her birth. Pearl‘s character is closely tied to her birth, which justifies and makes the ―other worldliness‖ about her very important. She is a product and a symbol of the act of adultery, an act of love, an act of passion, a sin, and a crime. Hawthorne, the narrator, states, ―[Pearl] was worthy to have been

brought forth in Eden; worthy to have been left there, to be the plaything of the angels ….‖ However, she ―lacked reference and adaptation to the world into which she was born.‖

The Puritan community believed extramarital sex to be inherently evil and influenced by the devil, and, because Pearl is a product of her mother‘s extramarital sex, Hawthorne raises the issue of Pearl‘s nature. Can something good come from something evil? Is Pearl inherently evil because she was born from what the Puritans conceived to be an immoral, sinful union? Perhaps, thinks Hester, who is fearful at least of such a predetermined outcome. Our modern sensibilities, however, shudder at the implication that an immoral act between two adults necessarily means that a child born from that sexual affair will be inherently evil.

Hawthorne‘s condemnation of Puritanism continues in this chapter. His strongest rebuttal of the society‘s self-serving, false piety occurs when he ironically contrasts the Puritan community's treatment of Hester and God's treatment of her. He notes of Hester‘s fellow citizens, ―Man had marked this woman's sin by a scarlet letter, which had such potent and disastrous efficacy that no human sympathy could reach her, save it were sinful like herself.‖ Ironically juxtaposed against the Puritan‘s sentence that Hester wear the scarlet letter A is ―God, [who] as a direct consequence of the sin which man thus punished, had given her a lovely child, … o be finally a blessed soul in heaven!‖ The comparison between the

community‘s (Puritan‘s) and God‘s responses to Hester‘s extramarital affair is dramatic.

Glossary

anathemas curses things or persons greatly detested.

sprit elf-like.

gesticulation a gesture, esp. an energetic one.

Luther Martin Luther (1483-1546), the first rebel against Catholicism; leader of the Protestant Reformation in Germany Chapter 7

Hester has heard that certain influential citizens feel Pearl should be taken from her. Alarmed, Hester sets out with Pearl for Governor Bellingham's mansion to deliver gloves that he ordered. More important, however, Hester plans to plead for the right to keep her daughter.

Pearl has been especially dressed for the occasion in an elaborate scarlet dress, embroidered with gold thread. On the way to the governor‘s mansion, Hester and Pearl are accosted by a group of Puritan children. When they taunt Pearl, she shows a temper as fiery as her appearance, driving the children off with her screams and threats.

Reaching the Governor's large, elaborate, stucco frame dwelling, Hester and Pearl are admitted by a bondsman. Inside a heavy oak hall, Hester and Pearl stand before Governor Bellingham's suit of armor. In its curved, polished breastplate, both Hester's scarlet A and Pearl are distorted. Meanwhile, as Hester contemplates her daughter‘s changed image, a small group

-12-

of men approaches. Pearl becomes quiet out of curiosity about the men who are coming down the path.

In addition to preparing the way for the dramatic and crucial interview to come between Hester and the governor, this chapter displays Hawthorne‘s imagination in developing Pearl‘s strange nature and the scarlet symbol. Like a symphony with variations, the assorted scarlet references in this chapter add to the richness of the letter‘s meaning.

Hester comes to Governor Bellingham‘s house because she has heard that people—particularly the governor—want to deprive her of Pearl. Once again Hawthorne shows his disdain for the smug attitudes of the Puritans. They reason that their ―Christian interest‖ requires them to remove Pearl—the product of sin—from her mother‘s influence. If Pearl is ―capable of moral and religious growth‖ and perhaps even salvation, they see it as their ―duty‖ to move her to a more trustworthy Christian influence. Hawthorne chides these self-righteous Puritans and likens their concern to a dispute in Puritan courts involving the right of property in a pig.

Hawthorne also designs this chapter to advance the reader‘s knowledge of Pearl, both in appearance and actions. She is constant motion with ―rich and luxuriant beauty.‖ Her actions are full of fire and passion. When the Puritan children fling mud at Pearl, she scares them off. She is an ―angel of judgement,‖ an ―infant pestilence.‖ Once her fire is spent, she returns quietly to her mother and smiles. Her actions seem to be preternatural behavior in such a young child. Her scarlet dress, a product of Hester‘s imagination and needle, seems to intensify her ―fire and passion.‖ Pearl‘s scarlet appearance is closely associated with the scarlet letter on Hester‘s bosom, and Hawthorne continues this relationship as the novel unfolds. When Hester is told the governor cannot see her immediately, she firmly tells the servant she will wait. Her determined manner indicates to the servant how strongly she feels about the issue of Pearl‘s guardianship. Because the servant is new in the community, he has not heard the story of the scarlet letter. The beautifully embroidered emblem on her dress and her determination cause him to think she is a person of some influence. Hawthorne emphasizes the servant‘s recent arrival to impress upon the reader the well-known nature of the scarlet letter‘s story.

Bellingham‘s house is described as a mansion of fantasy: cheery, gleaming, sunny, and having ―never known death.‖ It comes to life as the only interior description in the novel. Bellingham‘s home is a mixture of stern Puritan portraits and Old World comforts. Is it any wonder that the polished mirror of the breastplate on Bellingham‘s armor plays tricks on the eyes? Here in this fortress of Puritan rules where men will decide her fate, Hester virtually vanishes behind the scarlet A in the breastplate‘s reflection. Even Pearl‘s naughtiness and impish qualities are exaggerated—at least in Hester‘s mind—as if to defy the stifling, moralistic atmosphere of this place. The governor and his cronies arrive, and Pearl lets out an eerie scream. Their future approaches.

Glossary

cabalistic figures secret or occult figures.

a folio tome; here, a large book.

Chronicles of England a history of England by Holinshed, written in 1577.

tankard a large drinking cup with a handle and, often, a hinged lid.

steel headpiece, a cuirass, a gorget, and greaves … gauntlets here, all parts of a suit of armor.

Pequot war raids on Indian villages by Massachusetts settlers in 1637.

Bacon, Coke, Noye and Finch English lawyers of the 16th and 17th centuries who added to British common law. exigencies great needs; a situation calling for immediate action or attention.

eldritch eerie, weird.

Chapter 8

The group of men approaching Hester and Pearl include Governor Bellingham, the Reverend John Wilson, the Reverend Dimmesdale, and Roger Chillingworth, who, since the story's opening, has been living in Boston as Dimmesdale's friend and personal physician.

The governor, shocked at Pearl's vain and immodest costume, challenges Hester's fitness to raise the child in a Christian way. He asks Reverend Mr. Wilson to test Pearl's knowledge of the catechism. Pearl deliberately pretends ignorance. In answer to the very first question—―Who made thee?‖—Pearl replies that she was not made, but that she was ―plucked … off the bush of wild roses that grew by the prison door.‖

Horrified, the governor and Mr. Wilson are immediately ready to take Pearl away from Hester, who protests that God gave

-13-

Pearl to her and that she will not give her up. Pearl is both her happiness and her torture, and she will die before she relinquishes her. She appeals to Dimmesdale to speak for her. Dimmesdale persuades Governor Bellingham and Mr. Wilson that Hester should be allowed to keep Pearl, whom God has given to her as both a blessing and a reminder of her sin, causing Chillingworth to remark, ―You speak, my friend, with a strange earnestness.‖ Pearl, momentarily solemn, caresses Dimmesdale's hand and receives from the minister a furtive kiss on the head.

Leaving the mansion, Hester is approached by Mistress Hibbins, Governor Bellingham's sister. Hester refuses the woman's invitation to a midnight meeting of witches in the forest, saying she must take Pearl home, but she adds that, if she had lost Pearl, she would willingly have signed on with the devil.

This chapter brings back together the major characters from the first scaffold scene—Hester, Pearl, Dimmesdale, and Chillingworth—as well as representatives of the Church, the State, and the World of Darkness. Note, too, that underneath the surface action, Hawthorne offers several strong hints concerning the complex relationships of his characters. In Hester's appealing to Dimmesdale for help, in Pearl's solemnly caressing his hand, and in the minister's answering kiss lie solid hints that Dimmesdale is Pearl's father.

Hester calls on her inner strength in her attempt to keep Pearl. She argues quite eloquently that the scarlet letter is a badge of shame to teach her child wisdom and help her profit from Hester‘s sin. However, Pearl‘s refusal to answer the catechism question causes the decision of the Church and the State to go against her. Now Hester‘s only appeal is to Dimmesdale, the man whose reputation she could crush.

Pearl once again reveals her wild and passionate nature. In saying that her mother plucked her from the wild roses that grew by the prison door, she defies both Church and State. While such an answer seems precocious for a small child, the reader must remember that Hawthorne uses characters symbolically to present meaning. Pearl‘s action recalls Hester‘s defiance on the scaffold when she refuses to name the father of her child. The dual nature of Pearl‘s existence as both happiness and torture is restated in Hester‘s plea, and this point is taken up by Dimmesdale. The minister‘s weakened condition and his obvious nervousness suggest how terribly he has been suffering with his concealed guilt.

Nevertheless, Dimmesdale adds to Hester‘s plea when he states that Pearl is a ―child of its father‘s guilt and its mother‘s shame‖ but still she has come from the ―hand of God.‖ As such, she should be considered a blessing. The minister argues that Pearl will keep Hester from the powers of darkness. And so she is allowed to keep her daughter. Those powers of darkness can be seen in both the strange conversation with Mistress Hibbins and also in the change in Chillingworth.

As if to prove that Hester will be kept from the darkness by Pearl, Hawthorne adds the scene with Mistress Hibbins. While Mr. Wilson says of Pearl, ―that little baggage has witchcraft in her,‖ Hester says she would willingly have gone with the Black Man except for Pearl.

These dark powers are also suggested by the fourth main character, Chillingworth. The change noted by Hester in Chillingworth's physical appearance, now more ugly and dark and misshapen, is a hint that in the scholar's desire for revenge, evil is winning the battle within him and is reflected in his outward appearance. That Chillingworth is

Dimmesdale's personal physician :and supposed friend gives him the opportunity to apply psychological pressure on the minister. Chillingworth‘s comment on Dimmesdale's strange earnestness and his statement that he could make a ―shrewd guess at the father‖ suggest that he may already have decided on Dimmesdale's guilt.

The battlefield has been marked: The forces of light and darkness are vying for human souls.

Glossary

King James King James I (1603-1625) of England. He ordered the translation of the Bible, now called the King James Version.

John the Baptist the preacher who announced in the Bible the coming of Jesus. He was beheaded by Herod whom he accused of adultery.

John Wilson the Reverend John Wilson (1588-1667), a minster who was considered a great clergyman and teacher. He was a prosecutor of Anne Hutchinson.

physic [ Archaic] medicine.

the Lord of Misrule a part acted out in court masques in England during the Christmas season. He was part of a pagan, not Christian, myth.

-14-

a pearl of great price see the story in Matthew 13:45-46, about a merchant who sold all his goods for one pearl of great worth, which represents the kingdom of heaven. Wilson is saying here that Pearl may find salvation.

New England Primer a book used to teach Puritan children their alphabet and reinforrce moral and spiritual lessons. Westminster Catechism printed in 1648, it was used to teach Puritan religious lessons and the pillars of church doctrine. tithing-men men who collect church taxes.

Chapter 9

Since first appearing in the community, Chillingworth has been well received by the townspeople, not only because they can use his services as a physician, but also because of his special interest in their ailing clergyman, Arthur Dimmesdale. In fact, some of the Puritans even view it as a special act of Providence that a man of Chillingworth's knowledge should have been ―dropped,‖ as it were, into their community just when their beloved young minister's health seemed to be failing. And, although Dimmesdale protests that he needs no medicine and is prepared to die if it is the will of God, he agrees to put his health in Chillingworth's hands. The two men begin spending much time together and, finally, at Chillingworth's

suggestion, they move into the same house, where, although they have separate apartments, they can move back and forth freely.

Gradually, some of the townspeople, without any real evidence except for the growing appearance of evil in

Chillingworth's face, begin to develop suspicions about the doctor. Rumors about his past and suggestions that he practices ―the black art‖ with fire brought from hell gain some acceptance. Many of the townspeople also believe that, rather than being in the care of a Christian physician, Arthur Dimmesdale is in the hands of Satan or one of his agents who has been given God's permission to struggle with the minister's soul for a time. Despite the look of gloom and terror in

Dimmesdale's eyes, all of them have faith that Dimmesdale's strength is certain to bring him victory over his tormentor The theme of good and evil battling is carried through in Chapter 9, ―The Leech,‖ a ponderous and philosophical chapter with little action and much positioning of characters. We see the double meaning of the word ―leech,‖ the decline of

Dimmesdale under his weight of guilt, the development of his relationship with Chillingworth, and the point of view of the townspeople, which have strikingly opposing opinions about the influence of Chillingworth on the minister. As he

ingratiates himself with the young minister, and the town sees Chillingworth as ―a brilliant acquisition.‖ On the other hand, they suspect that the relationship and proximity of Chillingworth and Dimmesdale have led to Dimmesdale‘s deterioration. Hawthorne purposely uses the old-fashioned term ―leech‖ for ―physician‖ because of its obvious double meaning. As a doctor, Chillingworth seems to be making complicated medicines that he learned at the feet of the Indians; he also appears to be sucking the life out of Dimmesdale.

Chillingworth‘s devious and evil nature is developed in this chapter. As he moves into a home with Dimmesdale and the two freely discuss their concerns, there begins to develop ―a kind of intimacy‖ between them. To Dimmesdale,

Chillingworth is the ―sympathetic‖ listener and intellectual whose mind and interests appeal to him. The reader, however, is told that, from the time Chillingworth arrived in Boston, he has ―a new purpose, dark, it is true.‖ As Chillingworth

becomes more and more absorbed in practicing ―the black art,‖ the townspeople notice the physical changes in him, and they begin to see ―something ugly and evil in his face.‖ His laboratory seems to be warmed with ―infernal fuel,‖ and the fire, which also leaves a sooty film on the physician‘s face, appears to come from hell.

As the people in town watch this struggle, they feel that this disciple of Satan cannot win and that the goodness of

Dimmesdale will prevail. Dimmesdale, however, is not so sure. Each Sunday, he is thinner and paler, struggling under the unrevealed guilt of his deed. The occasional habit of pressing his hand to his ailing heart has now become a constant gesture. He turns down suggestions of a wife as a helpmate, and some parishioners associate his illness with his strong devotion to God. Dimmesdale, although he discusses the secrets of his soul with his physician, never reveals the ultimate secret that Chillingworth is obsessed with hearing. Their relationship is further explored in the next few chapters. Glossary

appellation a name or title that describes or identifies a person or thing.

ignominious shameful; dishonorable; disgraceful.

deportment the manner of conducting or bearing oneself; behavior; demeanor.

Elixir of Life a subject of myth, a substance that was supposed to extend life indefinitely.

-15-

pharmacopoeia a stock of drugs.

Oxford Oxford University in England.

importunate urgent or persistent in asking or demanding; insistent; refusing to be denied; annoyingly urgent or persistent. New Jerusalem might mean Boston, the city on the hill.

healing balm an ointment used for healing.

Gobelin looms a tapestry factory in Paris that made the finest tapestries.

David and Bathsheba the biblical story of King David‘s adultery with Bathsheba.

Nathan the Prophet the biblical prophet who condemned David‘s adultery.

erudition learning acquired by reading and study; scholarship.

vilified defamed or abused.

commodiousness the condition of having plenty of room; spaciousness.

Sir Thomas Overbury and Dr. Forman the subjects of an adultery scandal in 1615 in England. Dr. Forman was charged with trying to poison his adulterous wife and her lover. Overbury was a friend of the lover and was perhaps poisoned Chapter 10

In this and the next few chapters, Chillingworth investigates the identity of Pearl‘s father for the sole purpose of taking revenge. Adopting the attitude of a judge seeking truth and justice, he quickly becomes fiercely obsessed by his search into Dimmesdale's heart. He is frequently discouraged in his attempts to pry loose Dimmesdale's secret, but he always returns to his ―digging‖ with all his intelligence and passion.

Most of Chapter 10 concerns the pulling and tugging by Chillingworth at the heart and soul of Dimmesdale. One day in Chillingworth‘s study, they are interrupted in their earnest discussion by Pearl and Hester‘s voices outside in the graveyard. They comment on Pearl‘s strange behavior and then return to their discussion. Watching Hester and Pearl depart,

Dimmesdale agrees with Chillingworth that Hester is better off with her sin publicly displayed than she would be with it concealed.

When Chillingworth renews his probing of Dimmesdale's conscience, suggesting that he can never cure Dimmesdale as long as the minister conceals anything, the minister says that his sickness is a ―sickness of the soul‖ and passionately cries out that he will not reveal his secret to ―an earthly physician.‖ Dimmesdale rushes from the room, and Chillingworth smiles at his success.

One day, not long afterward, Chillingworth finds Dimmesdale asleep in a chair. Pulling aside the minister's vestment, he stares at the clergyman's chest. What he sees there causes ―a wild look of wonder, joy, and horror,‖ and he does a spontaneous dance of ecstasy.

This chapter allows the reader to witness Chillingworth's evil determination to accomplish his revenge on and to increase the painful inner suffering of young Arthur Dimmesdale. The reader is also given the best insight yet into the nature of Dimmesdale's tortured battle with himself. Clearly, the struggle within his soul is destroying him, as evidenced by his physical appearance and his mental anguish, yet he still cannot confess his role in the adulterous affair with Hester. It should be noted that Dimmesdale articulates his justification for his silence, but, in the face of Chillingworth's diabolical logic and questioning intended to manipulate the minister into a confession of his sin, Dimmesdale breaks off the colloquy. Hawthorne refers in this chapter to Chillingworth‘s earlier reputation as once a ―pure and upright man.‖ His shadowy and fiendish descriptions and images of him, however, further develop his symbolic representation of one who now appears to be doing the work of the devil. Just as he was earlier connected to the devil by soot and fire, now Hawthorne uses an allusion to the door of hell in Bunyan‘s Pilgrim‘s Progress and a reference to the breach of physician-patient relationship and trust in describing Chillingworth as ―a thief entering a chamber where a man lies only half asleep‖ to further emphasize his evilness.