借势增长 破浪前行:20xx年全球财富报告

波士顿咨询公司(BCG)发布最新报告《借势增长 破浪前行:20xx年全球财富报告》。报告指出,20xx年全球私人财富的增长或已超出原本预期,这一点在发达市场尤为明显。尽管如此,财富管理机构仍需在多个领域采取必要措施,以期在未来几年继续扩大市场份额并提高利润。

本报告是BCG发布的第14份关于全球财富管理行业研究的年度报告。报告全面揭示了全球财富管理市场目前的规模、领先机构的业绩水平以及离岸银行业务的状况。报告还深入分析了正在塑造行业格局的重要趋势,包括数字技术日渐增长的重要性以及对最佳业务模式的追求。最后,报告还为财富管理机构提供了清晰明确的行动指南,帮助它们延续20xx年的出色业绩并更上一层楼。

报告作者之一、BCG资深合伙人Brent Beardsley表示:“财富管理机构在发达经济体所面临的重要挑战是在多变的增长模式下充分利用大量现有资产基础,而它们在发展中经济体的任务则是在当地新增财富中获得可观的份额。总体而言,从现在直到20xx年, 财富管理机构对资产和市场份额的竞争将日趋激烈。”

市场规模。报告显示,全球私人金融财富在20xx年增长了14.6%,总额达到152万亿美元。这一增幅高于20xx年8.7%的增长水平。与20xx年一样,20xx年全球私人金融财富的增长依然主要归功于股票市场的表现和快速发展经济体(RDE)的新增财富。

从区域划分上看,亚太(不包括日本)的私人财富增长最为强劲,增幅高达30.5%。其次为东欧、北美、中东和非洲、以及拉美,增幅分别为17.2%、15.6%、11.6%和11.1%(在不考虑许多拉美国家出现货币贬值的情况下以固定汇率计算)。相比之下,西欧和日本的私人财富增长较为温和,增幅分别为5.2%和4.8%(在不考虑日元走弱的情况下以固定汇率计算)。亚太(不包括日本)有望在20xx年取代西欧成为全球第二富裕的地区,并在20xx年取代北美成为全球最富裕的地区。全球私人财富预计将在未来五年中实现5.4%的年均复合增长率。到20xx年底,全球私人财富总值估计将达到198.2万亿美元。

百万美元资产家庭。报告指出,20xx年全球百万美元资产家庭总数达到1,630万户,远超20xx年的1,370万户,占全球家庭总数的1.1%。其中美国是拥有百万美元资产家庭最多的国家,数量高达710万,其新增百万美元资产家庭的数量也是最多的,达到110万。中国的百万美元资产家庭总数从20xx年的150万增至20xx年的240万,体现出中国私人财富的强劲增长势头。受到日元兑美元汇率下跌15%的影响,日本的百万美元资产家庭总数从150万降至120万。

离岸财富。20xx年,跨境私人财富达到了8.9万亿美元,比20xx年增长了10.4%,但低于14.6%的全球私人财富的增长水平。因此,离岸财富在全球私人财富中的占比略有下降,从6.1%降至5.9%。此后,离岸财富预计将以6.8%的年均复合增长率稳健增长,到20xx年底达到12.4万亿美元。这主要是由于发展中经济体的投资者趋向于寻求更高的政治和金融稳定性、更具深度的财富管理产品和专业知识、以及地域上的多样性。瑞士仍然是全球领先的离岸财富中心,资产总额达到2.3万亿美元,占全球离岸资产总值的26%。但由于大量资 1

产来自发达经济体,瑞士仍然承受着巨大的压力。当各国政府纷纷采取措施以解决逃税问题后,部分资产预计将被转移回国。泛言之,在当前环境下,财富管理机构必须确保在其服务的所有市场中完全遵循当地的各项监管法规。

财富管理机构基准比照。BCG对包括私人银行和大型全能银行集团的财富管理部门在内的130多家财富管理机构的业绩进行了基准比照。继20xx年后,财富管理机构于20xx年再次实现出色增长,管理资产额(AuM)增长了11%(20xx年管理资产额增幅为13%)。这主要得益于股市不断上涨所带来的资产升值。然而,尽管财富管理机构的管理资产额取得了大幅增长,但其利润率却基本变化不大,这主要归因于成本的不断上涨,特别是那些因遵循监管法规而增加的成本。

数字化困境。数字通信的不断发展和应用将重塑财富管理机构向客户提供产品、服务和建议的方式。技术可以改变财富管理机构的竞争优势来源。然而,许多财富管理机构未能充分利用数字技术来真正提升其整体产品和服务水平。报告显示,随着客户期望值的不断提高,财富管理机构必须将开发先进的数字技术作为企业发展议程的重要内容,并使数字技术与其现有的渠道和业务模式完美融合。

报告作者之一、BCG合伙人Daniel Kessler表示:“未来的发展道路不会一帆风顺。不论身处任何区域市场,财富管理机构若能找到与自身资源、能力和发展愿景相契合的最佳业务模式,并能成功实施选定的战略,就有望在竞争中拔得头筹。而市场的持续上扬将为财富管理机构的成功助一臂之力。”

(来源:中国财富管理与私人银行门户网站 ——e财富管理网)

2

第二篇:美国波士顿咨询公司报告:新全球挑战者

R

BCG G C

Companies on the MoveRising Stars from Rapidly Developing Economies Are Reshaping Global Industries

BCG G CSharad Verma

Kanika Sanghi

Holger Michaelis

Patrick Dupoux

Dinesh Khanna

Philippe Peters

January 2011

bcg.com

? The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. 2011. All rights reserved.For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at:E-mail: bcg-info@bcg.com

Fax: +1 617 850 3901, attention BCG/Permissions

Mail: BCG/Permissions

The Boston Consulting Group, Inc.

One Beacon Street

Boston, MA 02108

USA

Contents

Executive Summary A Decade of Global Growth

Strong Revenue Growth and Profits Superior Value Creation

Aggressive Moves in Cross-Border M&A Activity

4667711111xxxxxxxxxxxx222223242829

The 2011 BCG Global Challengers

Who They Are

The 2011 BCG Global Challenger Emeriti

The Countries and Industries of the 2011 Global Challengers Five Trends That Will Shape the Future

The Success of Challengers

Bharti Airtel’s Operations and Channel Innovations Indorama Ventures’ Contrarian Bent

The Technological Focus of Grupo Alfa’s Nemak

The New Decade

The Battle for Emerging Customer Segments The Battle for Industry Leadership The Battle for New Markets

For Further Reading Note to the Reader

C M

Executive Summary

G

lobal challengers are companies based in rapidly developing economies (RDEs) that are shaking up the established eco-nomic order.

the world stage. These are the emergence of Chinese contractors, the rush for natural resources, the rise of diversi? ed global conglomerates, the challenges of building global consumer brands, and the increasing reliance on partnerships.

The global challengers are entering the new decade from a position of strength.

? They have developed innovative business models and understand emerging markets, which will serve as the growth engines of the global economy. nancially ? t and can take advantage of ? They are ?

opportunities to buy attractive assets and compete against more established competitors still in recov-ery mode.Many challengers are taking on established multi-nationals, vying for global leadership.

ve years, about 50 of the global ? Within the next ?

challengers could qualify for inclusion in the Fortune Global 500. ? By 2020, the global challengers could collectively generate $8 trillion in revenues, an amount roughly equivalent to what the S&P 500 companies generate today.Increasingly, global challengers will be engaged in three key battles with companies from developed markets.

? A Battle for Emerging Customer Segments. The middle class in emerging markets will make up 30 percent of

T B C G

ed in this re-? The global challengers identi?

port grew annually by 18 percent and averaged oper-ating margins of 18 percent from 2000 through 2009.

? During these years, the annualized total shareholder return of the global challengers was 17 percent.? These companies are also aggressively acquiring for-eign companies in order to expand their reach, acquire brands and technological expertise, and build scale.The 2011 global challengers are a diverse group, re-? ecting the dynamic nature of global competition.? They come from 16 countries, with China, India, Brazil, Mexico, and Russia dominating the list—although less so than they did in past reports.? Africa, a continent with new-found ambitions, placed four companies on the list.? Four industries—mining and metals (with nine chal-lengers), steel (with eight), construction (with six), and fossil fuels (with six)—signal the rising importance of infrastructure and natural resources to the ultimate success of developing economies and companies head-quartered in these economies. ve trends ? Across the 100 global challengers, at least ?

emerge that will shape commerce, not just for the global challengers but for all companies that play on

the global population by 2020. Many challengers have already built successful businesses serving these con-sumers, but they need to fortify these positions and consider diversi? cation and expansion.? A Battle for Industry Leadership. Over the coming de-cade, the battle between established players and glob-al challengers will intensify. The challengers need to move beyond advantages that are based on cost and location to create global organizations, strong brands, and world-class innovation capabilities. ? A Battle for New Markets. There are several emerging battlegrounds: Africa, an o en-neglected continent; do-mestic markets within RDEs; trade with other RDEs; and small and midsize cities rather than the well-known megacities. Challengers can take advantage of their knowledge of these markets to develop relevant products and compelling brands that stand for quality and value.Competition between global multinationals and chal-lengers will intensify over the coming decade. es, the boundaries between ? As competition intensi?

these two distinct sets of companies will continue to blur. ? During the new decade, winning global companies will be identi? ed less by their home market and more by how they adapt to and embrace the fast-moving world in which they operate.

About the Authors

Sharad Verma is a partner and managing di-rector in the New Delhi o? ce of The Boston Consult-ing Group; you may contact him by e-mail at verma.sharad@bcg.com. Kanika Sanghi is a proj-ect leader in the ? rm’s Mumbai o? ce; you may con-tact her by e-mail at sanghi.kanika@bcg.com. Holger Michaelis is a partner and managing director in BCG’s Beijing office; you may contact him by e-mail at michaelis.holger@bcg.com. Patrick Dupoux is a partner and managing director in the firm’s Casablanca office; you may contact him by e-mail at dupoux.patrick@bcg.com. Dinesh Khanna is a part-ner and managing director in BCG’s Singapore office; you may contact him by e-mail at khanna.dinesh@bcg.com. Philippe Peters is a partner and managing director in the ? rm’s Moscow o? ce; you may contact him by e-mail at peters.philippe@bcg.com.

C M

A Decade ofGlobal Growth

F

ive years ago, when the ? rst report in this se-ries was released, global challengers were still a novelty. Lenovo Group had recently purchased the PC business of IBM, and the Chinese National O? shore Oil Corporation

had made an unsolicited bid for Unocal. But the novelty has become the norm.

Western executives now fully recognize—even if they don’t thoroughly understand—the rise of companies with global aspirations from rapidly developing economies (RDEs).

Established Western brands such as Jaguar and Land Rover are now owned by Tata Group of India. Huawei Technologies and ZTE, both of China, are the second- and ? h-largest global manufacturers of mobile telecom equipment ranked by overall revenues, respectively. Mexico’s Grupo Bimbo is the largest bread baker in the world; Brazil’s JBS, the largest meat producer; and Rus-sia’s United Company Rusal, the largest producer of alu-minum.

These companies have been the hidden engines of the global economy in recent years. Despite the economic slowdown that closed the past decade, global per capita GDP rose by 50 percent, and 250 million people were li -ed out of poverty over the past ten years. Trade is freer now than a decade ago, and global exports have doubled.

Global challengers are also the public face of RDEs. Over the past decade, the share of global GDP generated by RDEs rose from 18 percent to 31 percent; their share of world trade jumped almost as much, from 18 percent to 28 percent.

As the economic pro? le of RDEs has increased, so has their in? uence. RDEs now account for half of the in? uen-tial G-20, an international group of ? nance ministers. Of the 29 RDEs we analyzed in this report, 25 are members of the World Trade Organization.

This rising economic tide has washed into global rank-ings. The number of companies from RDEs in the Fortune Global 500 has more than tripled—from 21 to 75—in the past decade. The 2010 list of Forbes 2000 companies in-cluded 398 companies from RDEs, nearly triple the num-ber just ? ve years ago. Global challengers are here to stay. While many develop-ing markets are still in economic recovery, global chal-lengers have maintained the momentum they built over the past decade.

Strong Revenue Growth and Profits

Revenues of the global challengers rose by 18 percent annually from 2000 through 2009, triple the average annual growth rate achieved by both global peers and the non? nancial ? rms among the S&P 500.1 Global chal-lengers have achieved this growth without sacri? cing margins. The average operating margin (earnings before interest and taxes, or EBIT) of global challengers that were publicly listed during those years was 18 percent—6 percentage points higher than the aver-age of the non? nancial constituents of the S&P 500. (See Exhibit 1.)

1. Global peers are multinational companies that are headquar-tered in developed economies and that operate in the same indus-tries as the global challengers.

T B C G

Superior Value Creation

The economic downturn took a toll on the total share-holder return (TSR) of nearly all companies. But the per-formance of the global challengers has bounced back much more quickly and strongly than that of other com-panies. From 2000 through 2009, the annualized TSR was 17 percent for the global challengers while it practically stood still for the S&P 500 and global peers and rose much more modestly for the MSCI Emerging Markets In-dex. (See Exhibit 2.) The global challengers have, in fact, resolved many of the traditional tradeo? s that companies make in pursuit of value creation. (See the sidebar “Re-solving Tradeo? s.”)

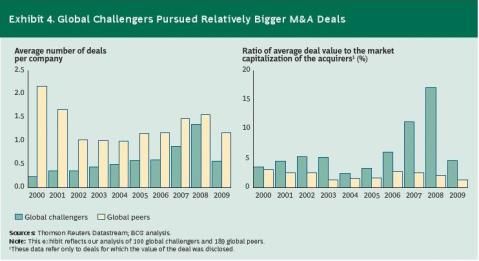

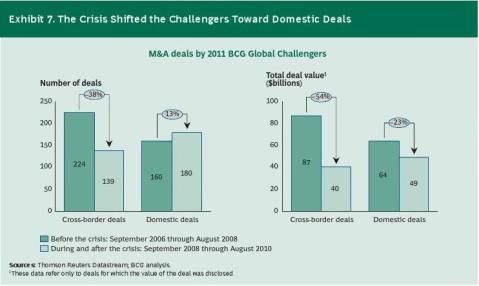

equivalent to the average in 2008. The challengers have

also been pursuing proportionately larger deals than their peers have. (See Exhibit 4.)

About 60 percent of the global challengers’ cross-border deals in the past decade have taken place in developed markets. Averaging $554 million, these deals have also been larger than those that the global challengers com-pleted in developing markets, which had an average val-ue of $337 million. This focus on developed markets has increased since the start of the recession. Global challeng-ers conducted 71 percent of their cross-border deals in developed markets in the two years a er the recession began, compared with 58 percent in the two prior years.

Aggressive Moves in Cross-Border M&A Activity

Global challengers have continued to pursue cross-border mergers and acquisitions aggressively. The number of outbound deals and their average value fell momentarily in 2009—a re? ection of economic uncertainty—but have since bounced back. Through August 2010, 56 deals had been announced, the same number announced in all of 2009. (See Exhibit 3.) The average value of the deals in 2010 was almost twice as high as in 2009 and roughly

C M

G

lobal challengers are on the hinge of history, bal-anced between a remarkable past decade of growth and innovation and a promising but un-proven future. Their future success will depend on wheth-er they can maintain their momentum over the new de-cade and continue to narrow the gap with global multinationals. They will have succeeded if, in ten years, the notion of global challengers is once again a novelty—because the distinction between them and global multi-nationals has been extinguished.

T B C G

C M

T B C G

The 2011 BCGGlobal Challengers

B

CG has selected a list of 100 global challeng-ers that are already sizable, are globally ex-pansive, and are taking a run at traditional multinational companies. As in past reports, our point in this exercise was not to pick in-dustry winners but to spotlight the innovative business models, strategies, and challenges emerging from the plethora of constraints in RDEs.

In selecting this year’s list, we undertook a rigorous screening process. (See the sidebar “Methodology for Se-lecting the 2011 BCG Global Challengers.”)

Anshan Iron and Steel Group (China) is one of world’s top-ten steel producers, with revenues of more than $15 billion. Over the past few years, the company has made a series of overseas and domestic acquisitions, in-cluding the 2010 acquisition of China’s Panzhihua Iron and Steel Group. The combined production capacity will propel Anshan to become one of the world’s leading steel producers.

Bharti Airtel (India), with more than 200 million sub-scribers, ranks among the largest telecom operators worldwide. The company generated revenues of $8.8 bil-lion in ? scal 2010 and has grown by an average of 38 per-cent annually over the last ? ve years. Spreading out from its base in India, Airtel has aggressively pursued acquisi-tions in other RDEs. With its $10.7 billion acquisition of Zain Africa’s mobile operations in 15 countries, the com-pany now has a presence in 19 countries.

Bidvest Group (South Africa) is a diversi? ed holding company with interests in food services, freight, manufac-turing, and automobile sales. It is the largest food-distri-bution company outside the United States. The company had revenues of $14.4 billion in ? scal 2010 and has a strong footprint in Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Bumi Resources (Indonesia) is among the fastest-grow-ing coal companies in the world. In 2009, Bumi posted

2. In addition to the 23 new companies on the 2011 list, there are five new names among the list of challengers. Brasil Foods (Brazil) is the product of a merger in 2009 of Sadia and Perdig?o, both of which were listed previously as challengers. DP World (United Arab Emirates) replaces its parent company, Dubai World. Grupo Alfa (Mexico) replaces its manufacturing subsidiary Nemak. Tata Tea has changed its name to Tata Global Beverages (India). United Company Rusal (Russia) replaces its parent company, Basic El-ement.

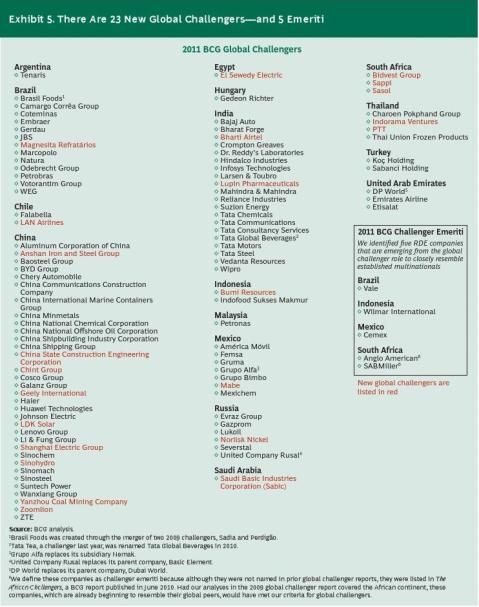

Who They Are

The global challengers list is as dynamic as the markets in which its members are located, with 23 new members in this report. (See Exhibit 5.)

In most cases, previous entrants that do not appear on the current list continue to be strong contenders in their respective industries, but they may not be expanding globally as aggressively as the currently listed companies are. Some companies have dropped from the global chal-lengers list because they su? ered during the economic downturn and are now focused on bringing their busi-nesses back to health.

In addition to the new entrants, we are also introducing in this report challenger emeriti—a new group we cre-ated to recognize companies that now more closely re-semble traditional multinationals than newcomers.2The 23 new additions to the BCG Global Challengers list are the following companies:

C M

Methodology for Selecting the 2011 BCG Global Challengers

We began our analysis by compiling a list of potential global challengers from companies based in RDEs. We fo-cused on companies located in Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Middle East, and Latin America. In this report, we also ex-panded the geographic reach of our analysis to include the African continent; we took this step to re? ect the dy-namic growth of the economies there.

Next, we applied a set of quantitative and qualitative cri-teria. We deemed company size important, as smaller

companies have fewer resources to mount aggressive globalization e? orts. We sought companies that already had high international revenues or large cross-border M&A deals; we also sought companies with credible aspi-rations to build truly global footprints, and we excluded those that could pursue only low-end, export-driven mod-els. We determined this globalization potential by analyz-Our initial master list of potential global challengers was ing each company’s international presence, the number drawn from local rankings of the top companies in the and size of its international investments over the past ? ve geographic markets listed above. We excluded joint ven-years, and the strength of its business model. We mea-tures and companies with signi? cant overseas equity sured the size of each company relative to that of other holders. We decided to consider a few companies that are challengers and multinational competitors in their indus-headquartered in ? nancial capitals—such as London, tries. We wanted to ensure that the global challengers are Hong Kong, and Singapore—on the condition that these credible contenders to become market leaders.companies’ operations take place primarily in RDEs.

These companies are listed in the RDE that houses most We based our selection of the ? nal 100 on these criteria of their operations.and feedback from industry experts around the world.

revenues of $3.2 billion, with the majority generated overseas. The company has a strong sales presence in Ja-pan, India, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Europe and has re-cently entered the Chinese market.

China State Construction Engineering Corporation (China) is a leading construction company, ranking sixth on Engineering News-Record’s Top 225 Global Contractors for 2010 and earning 2009 revenues of $22.4 billion. The company has undertaken more than 5,000 projects in 100 countries and has a signi? cant presence in North Africa, United Arab Emirates, India, and the United States. Chint Group (China) is a leading player in the low-volt-age transmission and distribution industries and has re-cently expanded into solar energy. It exports to more than 90 countries. Chint has a strong focus on R&D and has begun over the past ? ve years to create its own brands rather than simply supply equipment to other companies.

El Sewedy Electric (Egypt) is one of the leading electri-cal-equipment manufacturers in Africa and the Middle East, specializing in cables and power transformers. The company’s revenues grew by 35 percent annually, on av-erage, from 2004 through 2009 and reached $1.7 billion in 2009. El Sewedy focuses on underpenetrated markets

and is the sole producer of power transformers in many African countries. Its new wind-energy business is a pio-neer in renewable energy in the Middle East and North Africa.

Geely International (China) is one of the fastest-growing car manufacturers in China. In 2010, Geely agreed to pay $1.8 billion for Volvo Cars. Geely intends to preserve Vol-vo Cars’ existing manufacturing facilities in Sweden and Belgium while exploring opportunities to manufacture Volvo vehicles in new production facilities to be built in China for the local market.

Indorama Ventures (Thailand) is the largest global pro-ducer of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which is used to make plastic bottles, and it is the only PET producer with a manufacturing presence in the United States, Eu-rope, and Asia. The company’s revenues have grown an-nually by 60 percent since 2005, reaching $2.3 billion in 2009, with 85 percent of these revenues generated over-seas. Indorama Ventures focuses on cost control, tight in-tegration, and a contrarian growth strategy that has helped the company build scale through acquisitions in mature markets.

LAN Airlines (Chile) has domestic operations in ? ve South American countries—Argentina, Chile, Colombia,

T B C G

C M

Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (Sabic) (Saudi Ara-bia) is the largest and most pro? table Middle Eastern company outside the oil industry and one of the world’s LDK Solar (China) is a leading integrated manufacturer

largest manufacturers of chemicals, plastics, and fertiliz-of photovoltaic products and the world’s largest producer

ers. A series of acquisitions has expanded of multicrystalline wafers. In 2009, 75 per-

Sabic’s presence across more than 40 cent of its $1.1 billion in revenues originat-PTT aspires to become

countries. In 2009, Sabic had revenues of ed outside China. Since 2006, LDK Solar’s a member of the $27.5 billion.revenues have more than doubled an-Fortune 100 and plans nually.

Sappi (South Africa) is the leading pro-over the new decade to ducer of several types of ? ne paper. Most Lupin Pharmaceuticals (India) is a rap-invest $100 billion.of its facilities are located in Europe and idly growing pharmaceutical firm with

North America. In ? scal 2009, Sappi had both generic and branded products and a

revenues of $5.3 billion, with 87 percent originating out-sizable presence in the United States and Japan. The com-

side Africa.pany has made recent acquisitions in Australia, Germany,

Japan, Philippines, and South Africa, and it reported rev-enues of $1 billion in ? scal 2010.Sasol (South Africa) is the largest producer of synthetic

fuel and among the largest coal-mining companies in the world, with revenues of $16.1 billion in 2010—half from Mabe (Mexico) is the largest home-appliance manufac-

international sales.turer in Latin America. It has leveraged strategic alliances

with such companies as General Electric and Fagor to drive international growth. The company has 18 manu-Shanghai Electric Group (China) is one of China’s top-facturing facilities in the Americas, and its products are three manufacturers of electric equipment and one of the sold in 70 countries. The company’s revenues reached largest elevator manufacturers, with 2009 revenues of $4.5 billion in 2009.$8.4 billion. It has acquired technical and managerial

know-how through more than 50 joint ventures with lead-ing players such as Siemens and Mitsubishi. In 2010, Magnesita Refratários (Brazil) is the third-largest—and

Shanghai Electric acquired Goss International, a U.S. pro-the only fully integrated—global producer of refractory

vider of engineered goods, for $1.5 billion.products (materials resistant to the high temperatures

that are used in steel and cement production). The com-pany has 28 manufacturing facilities in South America, Sinohydro (China) is a leading construction ? rm that has the United States, and Europe, and it reported 2009 rev-captured more than half of the global hydropower-con-enues of $1.1 billion.struction market. Revenues in 2009 exceeded $11 billion.

The company has more than 200 projects under construc-tion in 46 countries. Its presence is particularly strong in Norilsk Nickel (Russia), which returns to the challenger

Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.list a er a hiatus in 2009, is the largest vertically integrat-

ed mining company in Russia and the largest global pro-ducer of nickel and palladium. It generated revenues of Yanzhou Coal Mining Company (China) is the ? rst Chi-$10.2 billion in 2009 and has sales networks across 20 nese coal company to be listed on both the New York and countries.Hong Kong stock exchanges. In 2009, the company gener-

ated $3 billion in revenues and acquired Felix Resources for $3.2 billion, making it the largest Chinese investor in PTT (Thailand), a state-owned oil and gas company, gen-

Australia.erated 2009 revenues of $46 billion, nearly half of which

came from its international trading business. The com-pany aspires to become a member of the Fortune 100 and Zoomlion (China) is a leading construction-machinery plans over the new decade to invest $100 billion—half of company and the largest manufacturer of concrete-mak- T B C GEcuador, and Peru. It has a strong focus on operational ef-? ciency. In August 2010, LAN Airlines announced a merg-er with TAM, the largest airline in Brazil. In 2009, the combined revenues of the airlines totaled $8.4 billion.it overseas. It has 44 exploration and production projects in 13 countries.

ing machinery. The company, which reported $3 billion in revenues in 2009, has grown annually by 60 percent since its founding in 1992. Zoomlion’s strong R&D culture has helped generate a wide range of products. In 2008, the company extended its presence to more than 70 coun-tries when it acquired Italy’s CIFA, a manufacturer of concrete equipment.

global producer of platinum and diamonds. Anglo Amer-ican has extensive mining operations in South Africa, Australia, and Latin America.

The 2011 BCG Global Challenger Emeriti

Some RDE-based companies have made such signi? cant progress in globalizing that

multinationals.they are starting to look and feel like es-tablished global multinationals. We call SABMiller (South Africa) is the world’s

such companies challenger emeriti and identi? ed them second-largest brewer, with operations and distribution using the following four key criteria:agreements in 75 countries. Its sells both premium beers

with global brands and leading local beers. SABMiller is the number-one or number-two brewer in many of its ? Size and Scale Required to Operate Globally. Achieved an-markets including the United States and several countries nual sales in 2009 of at least $20 billion

in Africa, Latin America, and Europe. In ? scal 2010, al-most 80 percent of SABMiller’s revenues of $26 billion ? International Sales. Had at least 75 percent of 2009

originated outside South Africa.sales originate outside the country where headquar-tered—or from international customers

Vale (Brazil) is the second-largest diversi? ed mining com-pany in the world, with a presence in 38 countries and ? Industry Leadership. Ranked as a top-? ve global com-activities in exploration, operations, and sales. It is the petitor in their industry

world’s largest producer of iron ore and the second-larg-est producer of nickel. Among large companies tracked ? Global Presence. Maintained global operations and

by BCG’s Value Creators team, Vale has the best ten-year footprint

record of creating value for shareholders. The company has succeeded through strong management practices, ag-The globalization journey is not over for these compa-gressive pricing strategy, and successful acquisitions. In nies, and they will continue to face challenges, as do all

2009, 85 percent of Vale’s revenues of $23.9 billion were global companies. But the challenger emeriti are further

generated internationally.ahead than their peers in the RDEs.

Five companies quali? ed as challenger emeriti. This list

includes two companies from South Africa that were not named in prior global challenger reports but were listed in The African Challengers, a BCG report published in June 2010. Had our analyses in the 2009 global challenger re-port covered the African continent, these South African companies, which are already beginning to resemble their global peers, would have met our criteria for global challengers.

Anglo American (South Africa) is one of the leading di-versi? ed-mining companies in the world and the largest

C M

Cemex (Mexico) is the third-largest producer of cement

and the largest producer of ready-mix concrete in the world. It operates in more than 50 countries in the Amer-icas, Europe, the Middle East, and the Pa-ci? c Rim. Cemex’s success rests on its ef-Some RDE-based

fective operations and marketing

companies are starting

strategies, as well as its proven ability to

to look and feel like integrate acquired companies. In 2009,

79 percent of Cemex’s $20.2 billion in rev-established global

enues were generated internationally.

Wilmar International (Indonesia), a leading global agri-business company, has an integrated business model that covers origination, processing, branding, and distribution. It is the largest global processor and merchandiser of palm and lauric oils and a major oil-palm plantation own-er. It is the largest oilseed crusher, edible-oil re? ner, and manufacturer of consumer pack oils in China. In India, it is one of the largest edible-oil re? ners and a leading pro-ducer of consumer pack oils. Wilmar sells its products in more than 50 countries, and, in 2009, 77 percent of Wil-mar’s $24 billion in revenues originated outside South-east Asia.

The Countries and Industries of the 2011 Global Challengers

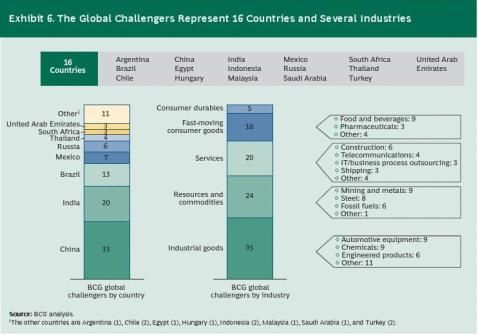

The global challengers come from 16 countries. (See Ex-hibit 6.)

Although China, India, Brazil, Mexico, and Russia still dominate the list of home nations for the global challeng-ers, countries in other regions are starting to compete for attention. In particular, Africa, with four global challeng-ers this year, will likely emerge as a region worth watch-ing. It is rich in natural resources, has emerged as a growth market for several industries, and has newfound ambition.

The global challengers have historically been well distrib-uted across industries. Industrial goods (with 35 challeng-ers) and resources and commodities (with 24) continue to lead the list. The construction industry (with 6 challeng-ers) moved up the list, re? ecting the increased focus on infrastructure in RDEs.

Five Trends That Will Shape the Future

Across the 100 global challengers, we have identi? ed at least ? ve emerging trends that will shape commerce—not just for the global challengers but for all companies that play on the world stage.

? The emergence of Chinese contractors? The rush for natural resources

? The rise of diversi? ed global conglomerates? The challenges of building global consumer brands? The increasing reliance on partnerships

The Emergence of Chinese Contractors. A group of previously unknown construction players from China has emerged to win prestigious multibillion-dollar projects. These companies are building a broad range of struc-

T B C G

tures: bridges and power plants in Southeast Asia, high-ways and railways in Africa, and even a casino in the United States.

Over the past decade, the average annual value of over-seas contracts for Chinese construction companies has expanded at a rate of 29 percent. These players are climb-ing the global rankings and capturing both market share and top positions. In the most recent Top 225 Global Con-tractor list published by Engineering News-Record, Chinese firms hold three of the top five—and 19 of the top 100—slots.

Three reasons are behind the success stories. The ? rst, of course, is cost. Even on overseas projects, Chinese com-petitors frequently enjoy a labor cost advantage over competitors from the United States, Europe, and Japan. They also tend to be vertically integrated and can buy equipment and material from domestic suppliers or their own subsidiaries. Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industry, the world’s largest manufacturer of heavy machinery, for ex-ample, provides container cranes for the projects of its parent, China Communications Construction.

The second reason is the talent and experience of Chi-nese contractors. Chinese contractors have gained valu-able experience domestically that they can apply on in-ternational projects. China, for example, has built 4,000 miles of high-speed rail lines, including the Wuguang Pas-senger Railway that allows trains to reach peak speeds of 245 miles per hour. China is also home to the Three Gorg-es Dam, the world’s largest hydroelectric project, com-pleted in 2006, and the Hangzhou Bay Bridge, the world’s longest sea-crossing bridge, opened in 2008.

The ? nal reason is that the Chinese government and state-owned banks provide diplomatic and ? nancial sup-port to contractors. The Chinese government has impor-tant ties with Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East—the three areas where 90 percent of Chinese over-seas orders originate.

The Rush for Natural Resources. Global challengers are searching for natural resources to fuel their growth. From January 2006 through August 2010, challengers in the re-sources and commodities industry announced 154 cross-border mergers and acquisitions, far more than any other sector and nearly twice the 86 M&A deals completed in the ? ve previous years.

C M

These deals have two signi? cant objectives: to satisfy the

local thirst for natural resources and to develop footholds in growth markets. In Thailand, for example, PTT is look-ing for foreign assets to meet fast-growing domestic de-mand. About one-half of its planned investment will fo-cus on overseas expansion. Brazil’s Petrobras plans to acquire long-term sources of lique? ed natural gas in the Asia-Paci? c region.In Russia, where more than 60 percent of export reve-nues are generated by oil and gas and 14 percent by met-als, companies are especially motivated and activated ac-quirers. (See the sidebar “Going Global.”)

As we saw with the rise of Chinese contractors, many of these acquisitions have strong ? nancial, regulatory, and diplomatic support from RDE governments. The debt of

Going Global

The Russian challengers, all of which operate in the natural resources industry, completed 143 cross-bor-der deals from 2000 through August 2010—accounting for 22 percent of these deals closed by all 100 global challengers.

Steel giant Severstal, for example, has an established record of acquiring and integrating assets in both de-veloped and emerging markets. Severstal’s $1 billion deal for PBS Coals in the United States will provide the raw materials and lower transportation costs need-ed to enable its expansion. In 2010, Severstal inked deals to secure iron-ore exploration rights in the Con-go and Gabon.

Rosatom, the state-owned nuclear-power monopoly and a leading global manufacturer of nuclear fuel and reactors, is seeking geographic diversi? cation and ac-cess to lower-cost uranium reserves. In 2010, it ac-quired a controlling stake in Canadian Uranium One. More broadly, Rosatom is seeking to become a global leader in nuclear technologies through international partnerships and M&A.

Oil and gas companies are not sitting still either. In ad-dition to scouting for new reserves, these companies are aiming to vertically integrate. In recent years, they have made a large number of downstream acquisitions (in pipelines, re? neries, and ? lling stations) across the world to gain better access to their customers.

many state-owned challengers is guaranteed implicitly or explicitly by their home-country government. In 2009, the Russian government set up a unit to advise on foreign M&A in the energy sector. Many Russian and Chinese companies have signed foreign-venture deals in Nigeria and Australia during o? cial visits by state dignitaries.The Rise of Diversi? ed Global Conglom-

erates. Seven global challengers are con-To expand the markets

Ko? Holding in Turkey takes a more de-glomerates; the most notable is the Tata they serve, some centralized approach, letting subsidiaries Group in India, which has operations in global challengers are seek growth opportunities. For instance, the chemical, communications, IT, bever-

Ko?’s Ar?elik subsidiary recognized that age, automotive, and steel sectors. (Six of trying actively to create the domestic Turkish market was saturat-the Tata Group companies qualify as chal-global brands. ed and began to expand its appliance busi-lengers in their own right.) The other di-

ness in Europe and beyond. To date, Ar?e-versified challengers are Grupo Alfa in

lik is the most global of Ko?’s subsidiaries.Mexico, Ko? Holding and Sabanci Holding in Turkey, and

Camargo Corrêa Group, Odebrecht Group, and Votoran-tim Group in Brazil. The Challenges of Building Global Consumer Brands.

In their bids to transcend business models that are based

These companies are at di? erent stages of globalization on low costs and to expand the markets they serve, some and diversi? cation. At one end of the spectrum are Tata global challengers are trying to create global brands. and Votorantim, major global contenders. Votorantim’s recent acquisition of Aracuz led to the creation of Fibria, Historically, many durable-consumer-goods companies the largest competitor in the pulp and paper industry. from RDEs have entered developed markets as original The Votorantim Group’s member companies are also equipment manufacturers, distributing goods through among the top-? ve global zinc companies and the top-ten better-known Western brands. This model has reached its global cement producers. At the other end are the con-limits, as manufacturing costs have risen and demand for glomerates with less diverse global portfolios. Grupo Alfa appliances in developed markets has dropped since the from Mexico, for example, is the world’s leading manu-global recession. Wages in China’s Guangdong province, facturer of high-tech aluminum cylinder heads and en-for example, rose by 11 percent in 2010. In India, copper gine blocks and has interests in refrigerated products and prices more than doubled in 2009. Since 2008, mean-polyester businesses. Companies have also adopted dif-while, demand in North America has dropped by 10 per-ferent management approaches to globalization. For Tata, cent and by 3 to 5 percent in Western Europe. Also, many globalization was a way to distribute risk and lessen its established global companies have created manufactur-dependence on the Indian economy. Although its opera-ing operations in RDEs, a move that erodes cost advan-tions are independently managed by group companies, tages held by companies based in developing markets. the corporate center plays an important role in de? ning shared values and vision, developing brand and market-In response to these developments, many traditional ing strategies, facilitating people development, measur-manufacturers have begun to build their brand identity ing performance, and creating common M&A practices. in developed markets. To better understand the needs of

Western customers, for example, China’s Haier has locat-

Over the last decade, the Tata Group has completed cross-ed R&D facilities in the region and hired local sta? . It has border acquisitions whose value exceeded $17.5 billion. also developed relationships with retailers to expand Among others, Tata Steel acquired the Anglo-Dutch steel its reach with customers. Mexico’s Mabe has acquired group Corus; Tata Chemicals acquired General Chemical Bosch’s Brazilian subsidiary. Turkish conglomerate Ko? Industrial Products, which is based in the United States; has both invested in developing its own Beko brand in Tata Motors acquired three car and truck lines; and Tata major European markets and acquired local brands in Global Beverages acquired Tetley Tea. other markets.

T B C GThe Tata Group works collaboratively with its acquisi-tions. The acquired companies generally remain separate organizations and have operational freedom, even when they operate in the same or related businesses as the ac-quiring company does, as was the case for Tetley and Corus. Tata also emphasizes the retention of top manag-ers. The glue that holds the acquisitions together is Tata’s corporate center.

Achieving Scale to Compete Globally. The merger of Perdig?o, Brazil’s largest food company, and Sadia, a large poultry exporter also based in Brazil, created a conglomerate ca-In its campaign to become the world’s largest beef pro-

pable of competing against global food gi-cessor, JBS acquired the Bertin brand in

ants. The new Brasil Foods—which boasts Brazil and the Pilgrim Pride and Swift When global

42 factories, more than 100,000 employees, brands in the United States. The Swi ac-challengers partner sales in 110 countries, and 24 o? ces around quisition also gave JBS access to distribu-with multinationals, the world—can compete in the United tion channels in Japan and Korea. Like-

States, Europe, and the Middle East. wise, Thai Union Frozen Products, one of they do so from a the world’s largest exporters of seafood, position of strength. Sharing High-Risk Investments. India’s Reli-has established strong market positions

ance Industries and Mexico’s Grupo Alfa overseas by acquiring leading foreign

are partnering along with U.S.–based Pioneer Natural Re-brands. Its ? rst major acquisition was Chicken of the Sea,

sources to develop American shale-gas reserves. The ven-the third-largest brand of canned tuna in the United

ture plans to build 1,700 drilling sites in unconventional States. More recently, it purchased MWBrands, gaining

locations.leading canned-seafood brands in the United Kingdom,

Ireland, Netherlands, France, and Italy.

Challengers o en pursue more than one of these ap-proaches in their bids to become global. VimpelCom, the Grupo Bimbo’s $2.8 billion acquisition of Weston Foods,

Russian mobile operator, has engaged in M&A activity to which boasted 13 percent market share in the United

access new markets, achieve scale, and create synergies. States, made the Mexican company the largest global

It recently announced mergers with the Italian mobile manufacturer of bread. In 2010, Grupo Bimbo agreed

operator Wind and with Egypt’s Orascom; the latter has to buy Sara Lee’s North American bakery business for

a strong footprint in the Middle East and North Africa. $959 million, further solidifying sales outside Mexico and

Once they receive regulatory approval, these deals will complementing the existing scale in its U.S. operations.

create one of the top-? ve mobile operators in the world—with $21 billion in annual revenues, 174 million subscrib-The Increasing Reliance on Partnerships. Global chal-

ers, and operations in 20 countries. lengers have been entering partnerships and joint ven-

tures for a long time, but the nature of those relationships

Furthermore, when global challengers partner with mul-is changing in two fundamental ways. First, they increas-

tinationals, they do so from a position of strength. In the ingly are joining forces with other global challengers rath-

past, these ventures were largely formed to transfer tech-er than established multinationals. The rising popularity

nology from the multinational to the challenger or to sat-of ventures and partnerships among global challengers

isfy regulatory requirements within RDEs. Now, the two rests on four pillars.

sides are more like partners. In 2010, India’s Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories partnered with GlaxoSmithKline to market Sharing Knowledge and Expertise. The best example of this

pharmaceutical products in emerging markets. The deal trend may be the joint venture between India’s Tata Mo-

brings together Dr. Reddy’s manufacturing capability and tors and Brazil’s Marcopolo. This venture, formed in 2006,

portfolio of branded products with the global commercial brings together Tata’s expertise in chassis and Marcopo-

capability of GlaxoSmithKline. Daimler and China’s BYD lo’s know-how in designing and building bus bodies. It is

Group, meanwhile, are sharing R&D e? orts to develop aimed at capturing share in such growing markets as In-

electric cars in China. The venture capitalizes on Daim-dia, South Africa, Russia, and the Middle East.

ler’s know-how in electric-vehicle architecture and safety with BYD’s excellence in battery technology and e-drive Gaining Access to New Markets. The joint venture of India’s

systems. Bharat Forge and China’s FAW Group unites two large

C M In the food and beverage sector, global challengers have a di? erent motivation to develop brands. They have well-known brands at home and are expanding their global footprints through acquisitions of brands and distribution networks in developed markets. forging companies. It gives Bharat Forge an entry into the Chinese auto market, while it enables FAW to leverage the global sales channel held by Bharat Forge.

The Success ofChallengers

T

he global challengers are certainly not the ? rst ? rms to emerge from developing econ-omies to achieve global leadership, but they are taking a di? erent path than their prede-cessors from Japan and South Korea did.

The Japanese and Korean globalization campaigns were built around organic growth—but the global challengers are growing both organically and through M&A. The Japanese and South Korean pioneers also developed a di? erent set of strengths than the global challengers have. Over time, Japanese companies became known for technological innovation, lean manufacturing, and brands that stood for quality, while South Korean companies de-veloped a reputation for making quality products at af-fordable prices. The global challengers are more varied in their approach. Notably, they are creating disruptive busi-ness models and coming up with new and better ways to get the job done in many industries. Three challengers exemplify this approach: Bharti Airtel, Indorama Ven-tures, and Grupo Alfa’s Nemak subsidiary.

considered the crown jewel among telecom operators—to Ericsson and other parties. Outsourcing allowed Airtel to ? exibly increase and manage its network capacity, es-sentially “building” minutes with the increased demand, just as a factory line accelerates in line with demand. This model has delivered multiple bene? ts to Airtel. First, it allowed Airtel to ramp up its network speedily. By low-ering its capital outlays, Airtel gained the ? nancial ? exi-bility to buy more spectrum. Second, as the ? rst mover in telecom outsourcing, Airtel won great terms with ven-dors, enabling it to lower operating costs below those of its main rivals. Finally, these deals freed up resources and management time and allowed the organization to focus on customer activities.

The company also developed new channels to help alle-viate the logistical challenges of doing business in India. It piggybacked on the existing distribution networks of fast-moving-consumer-goods companies and created a standardized process for expanding into new areas. These approaches have helped Airtel add subscribers signi? -cantly more rapidly than its nearest rival has.

Airtel’s innovations in outsourcing and distribution have paid o? handsomely. With an operating margin of 40 per-cent, it is the most pro? table company in India. Airtel’s average revenue per user is also almost 12 percent higher than that of its nearest competitor, even while its operat-ing costs per minute are 14 percent lower.

Bharti Airtel’s Operations and Channel Innovations

Bharti Airtel has grown to become the world’s ? h-larg-est mobile operator, as measured by the number of sub-scribers. From its base in India, the company has expand-ed into 19 countries—and is the leading mobile provider in 12 of them. The secrets to its success are innovative business models relating to operations and distribution. In 2004, Airtel developed what is known as its “minute factory” model. Under the model, Airtel took the radical step of outsourcing signi? cant parts of its network—long

Indorama Ventures’ Contrarian Bent

Thailand’s Indorama Ventures is a leading polyester and

PET company with global production facilities in the

T B C G

United States, Europe, and Asia. The company has grown from the tenth-largest to the top global producer over the past four years by having the courage to challenge con-ventional wisdom.

First, while most major competitors were drawn by high-growth rates to the East, Indorama Ventures concentrat-ed on the West, particularly the slower-growing but less crowded North American and European markets. Sec-ond, in the late 1990s, when other companies began to divest their low-margin PET businesses, Indorama Ven-tures acquired many of them, o en at prices below their replacement cost, and gained advantages of scale. Third, in order to improve their margins, many traditional com-panies directed R&D and marketing to specialty product lines. Indorama Ventures instead focused on the com-modity side of the business and optimized R&D and marketing costs. Fourth, at most companies, the polyes-ter line was part of a much broader portfolio of busi-nesses. By contrast, Indorama Ventures specialized al-most exclusively in polyester in order to ensure that it had both its ? nancial resources and best talent devoted to the business.

Indorama Ventures became the low-cost leader in the in-dustry through a relentless focus on operating e? ciency. Its plants were running at full capacity in 2009, for exam-ple, while the average utilization rate of its competitors was around 85 percent. Indorama Ventures also lowered the cost of puri? ed terephthalic acid (PTA), a key raw ma-terial, by locking in supplies and keeping transportation costs down. In the future, it will internally source as much as 80 percent of the raw material for its new U.S. plant in Alabama. Indorama Ventures’ presence on three conti-nents also helps to reduce its transportation costs and lower the risk of trade barriers or duties.

The company’s conviction that polyester is a core busi-ness and its focus on cost turbocharged its business. From 2005 through 2009 at Indorama Ventures, revenues grew sevenfold, pro? ts increased ninefold, and its stock price tripled.

The Technological Focus of Grupo Alfa’s Nemak

Nemak, a subsidiary of Grupo Alfa, is the global leader in producing aluminum auto components such as cylinder heads and engine blocks. From its base in Monterrey, Mexico, it has expanded its manufacturing operations into 12 countries and now generates 90 percent of its rev-enues from international sales.

The company, which serves all the major automakers, has greatly transcended its humble origins as a joint venture with Ford Motor. As its expertise grew, Nemak improved both its cost structure and technological sophistication. It has partnered with global leaders in automotive technol-ogy and made major investments in talent. Rather than simply taking advantage of location and labor costs, Ne-mak is now a world-class auto supplier known for techno-logical innovation, customer focus, and quality products. The company has several product-development centers around the world and hires from some of the best univer-sities. It has systematized R&D to reduce ine? ciency, pro-mote collaboration, and assure the sharing of best prac-tices. These measures have allowed Nemak to reduce its overall product-development cycle to less than six months—a reduction of 70 percent. Nemak involves cus-tomers early in product design in order to meet their needs and control production costs.

C M

The New Decade

T

he global challengers are entering the new decade from a position of strength. They have developed innovative business mod-els that extend beyond low cost. They have succeeded in entering new markets and are

well positioned in emerging markets. They are ? nancial-ly ? t and can take advantage of opportunities to buy at-tractive assets and compete against more established companies that may still be in recovery mode.

If they maintain their growth trajectories, they will ac-quire signi? cant status over the new decade. Within the next ? ve years, 50 of the global challengers could qualify for inclusion in the Fortune Global 500. Within ten years, 15 to 20 challengers may join the Fortune 100. By 2020, the challengers could collectively generate $8 trillion in revenues, an amount roughly equivalent to the collective revenues of the S&P 500 today.

These scenarios, however, could easily be disrupted by external economic events.

A shortage of resources or volatility in commodity pric-es could intensify the pressure to secure access to sup-plies. For instance, there is already a shortage in coking coal needed to produce steel. Challengers and global mul-tinationals alike are on the prowl for fresh supplies.

In addition to these external constraints, challengers will also be testing their organizational limits. While global challengers can learn from the experiences of global mul-tinationals, they also have unique issues to address. Many global challengers, for example, are still run by founders or their family members who have not yet passed the ba-ton to the next generation of leadership. Most have not yet built global brands or world-class R&D capabilities.Against this backdrop, global challengers will be compet-ing with established players. This competition will occur in three arenas: the battle for emerging customer seg-ments, the battle for industry leadership, and the battle for new markets.

The Battle for Emerging Customer Segments

Over the next 20 years, the ? ercest battle will be for the many billions who are joining the middle class. By 2020, the middle class in RDEs will account for 30 percent of the world’s population; by 2030, that ? gure will jump to 50 percent.

It will not, however, be easy to compete in these markets. Within RDEs, the “middle class” can be sliced many ways by preferences and spending patterns. The traditional chal-lenges of product development, marketing, pricing, sales, and distribution will be multiplied in these markets.Many global challengers are well poised to reach these consumers because the companies sprang to life serving the emerging middle classes in their home markets. Bra-zil’s Natura, for example, generates 60 percent of its rev-enues from its midrange cosmetics and fragrances. Galanz

T B C G

A shortage of talent will intensify the battle for high-quality employees. Talent is increasingly the most valu-able resource for ? rms. Within RDEs, local and multina-tional companies will battle for the best and brightest. Protectionism could dampen exports. Global trade is rising again a er falling o? during the economic down-turn, but protectionist sentiment still lingers.

Group in China has become the global leader in micro-wave ovens largely by focusing on the low end and the middle of the market.

This tug of war will play out di? erently in each industry. Over the past decade, established players have defended their chosen industries by taking one of the following four approaches:

These companies are exporting the expertise they gained in domestic middle-class markets to other markets. India’s ? Adapt the business model to stay competitiveBajaj Auto exempli? es this approach. For the low end of the market, Bajaj Auto redeveloped its ? Integrate RDEs into the global supplybasic-model Boxer 100cc motorcycle—a chainGlobal challengers are vehicle no longer o? ered in India—to win

exporting expertise

price-sensitive customers in Africa. For the ? Partner with or acquire challengers

gained in domestic higher end, it introduced the Pulsar model

in Indonesia to attract customers fond of ? Reinforce traditional strengthsmiddle-class markets high-tech and trendy products.

to other markets. Adapt the business model to stay com-Natura has been able to move into other petitive. In the ? rst half of the past de-markets in Latin America by carefully studying local cade, Indian IT ? rms grew rapidly, increasing their share

conditions and introducing tailored products. The com-of the global IT-services market from about 1 percent in

pany also relies on a direct sales force of 880,000 “beau-2000 to 4 percent in 2005. Such ? rms as Tata Consultan-ty consultants” in Brazil and 160,000 in the rest of cy Services, Wipro, and Infosys Technologies were win-Latin America to reach customers. These strategies ning large contracts internationally and enjoying strong

helped Natura boost international sales by 42 percent a er-tax margins that exceeded 20 percent. But Western in 2009.competitors quickly realized that if they wanted to com-pete e? ectively with these challengers they would need At the same time, established players are not stand-to radically lower their costs, and then they placed a big

ing still. They recognize the size of the prize and are bet on India. also seeking to develop new ways of reaching these cus-tomers. Since 2003, employment in India by IBM Global Services,

Accenture, and HP Enterprise Services has risen at an av-One Japanese computer-electronics ? rm, which had erage annual rate of 40 percent and now exceeds 150,000. been focused on the high-end market in China, launched Employment at the largest Indian IT ? rms has also grown low-price laptops and ? at-screen televisions in January during those years, but at a slower pace (28 percent). The 2010. It is promoting these products as it enters tier 3 move to India has helped the Western ? rms reduce the and tier 4 cities. The company is also revamping its de-cost gap with Indian companies and improve their mar-velopment strategy to increase its presence in the small-gins. In addition to leveraging India as a delivery center,

er cities, where the government’s stimulus package is these global peers are also establishing themselves as lo-expected to keep demand strong.cal competitors. Today, IBM is the largest company in the

domestic IT-services market in India, and it actively lever-ages the insights that it generates in the country across global markets. The Battle for Industry LeadershipEstablished players and global challengers are also com-peting for industry leadership. In some industries, the

established competitors have responded e? ectively to in-roads by challengers—but this is not true in others. In the new decade, the ability of many established players to re-main competitive will be tested. But so will the capacity of global challengers to create truly global organizations and footprints.

C M

Integrate RDEs into the global supply chain. We see this approach taking hold among multinationals in the automotive sector. Turkey, for example, has become a manufacturing hub, with such companies as Ford and Fiat Group establishing facilities there to serve both do-mestic and European demand. The BMW Group, mean-while, has set up international-procurement facilities in Chennai and Beijing as a part of its sourcing strategy.

Partner with or acquire challengers. In the pharma-global leaders in the telecom equipment industry. (See the sidebar “Big and Getting Bigger.”) ceutical industry, major companies have entered new

markets by acquiring or partnering with challengers. In 2009 and 2010, French pharmaceutical company Sano? -In the aerospace industry, Brazil’s Embraer continues to Aventis made several acquisitions to expand in Russia strengthen its position as the leading manufacturer of re-and other emerging markets. It acquired a 74 percent gional jets of up to 120 seats. Embraer focuses on high-stake in Bioton Wostok, a Russian insulin manufacturer, growth markets and on innovation aimed at creating air-and it also signed an agreement with Ros-craft that feature lower price tags and technologies to manufacture drugs locally. operating costs as well as higher reliabili-The battle for industry The acquisition of Czech generics manu-ty, comfort, and safety. Its Phenom busi-leadership is closer to

facturer Zentiva solidi? ed Sano? -Aventis’s ness jets, for example, have spacious inte-its start than its end. presence in Central and Eastern Europe—riors and require less maintenance than especially in Romania, Slovakia, Russia, other aircra in the category. The Phenom Challengers cannot and the Czech Republic, where it is the has a design life of 35,000 hours, an im-rest on their laurels.market leader. Elsewhere, Sano? -Aventis pressive length for such aircra . acquired Laboratorios Kendrick, the lead-ing generics company in Mexico, and Medley, the leading The battle for industry leadership is closer to its start generics company in Brazil.than its end. In the industries for which success turns

solely on cost advantage, global multinationals may ulti-mately ? nd themselves unable to compete. But there are Reinforce traditional strengths. In the consumer elec-many more industries in which they can be quite com-tronics industry, established multinationals have forti? ed

petitive if they adapt their business models to the new their traditional prowess in R&D and branding rather

normal of global competition. Challengers, meanwhile, than trying to compete solely on price. Such companies

cannot rest on their laurels. as Samsung and Sharp Electronics stayed away from the

conventional-television market in China, which was dom-inated by low-cost players. Instead, they focused on com-petitively priced ? at-screen televisions. Consumers voted The Battle for New Marketswith their pocketbooks and chose the ? at-screen prod-ucts, causing the conventional-television market to col-RDEs will likely grow at an annual average rate of lapse.5.5 percent over the next ten years, compared with just

2.6 percent for developed economies. And they will

At the same time, challengers in other industries capture about 45 percent of global GDP by 2020, com-are continuing to strengthen their positions. China’s pared with the 31 percent they command today. This Huawei Technologies and ZTE have quickly become growth will be produced not just by the usual suspects

Big and Getting Bigger

What a di? erence three years can make. In 2006, the wire-less equipment industry was dominated by Western com-panies but remained fairly fragmented. By 2009, industry consolidation had reduced the number of Western com-petitors. During the same period, China’s Huawei Tech-nologies rose from eighth to second place in the global rankings of equipment suppliers in terms of overall reve-nues, while ZTE rose from ninth to ? h. Huawei has certainly enjoyed having home ? eld advan-tage in the rapidly expanding Chinese telecom market,

but the company has also quickly expanded abroad. In

2002, three-quarters of Huawei’s sales were domestic; to-day, three-quarters now come from overseas. The compa-ny has also established R&D facilities in India, the United States, and Europe.

Still, established players are ? ghting back hard. Nokia Sie-mens Network, for example, has launched a large trans-formation plan designed to build its presence in low-cost countries, shi its business toward services, and focus its organization around RDEs.

T B C G

of Brazil, China, India, and Russia, and Mexico. When these ? ve countries are excluded, the 40 countries pro-jected to have the highest growth in real GDP over the new decade include 18 countries in Africa, Eastern Eu-rope, and Latin America. By 2020, many new countries are likely to join the ranks of the top 40 nations listed by GDP.

Four trends are likely to emerge from these growth sce-narios.

New Scrimmages. Africa, Latin America, and parts of Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia will emerge as the next markets where multinationals and challengers com-pete for customers and leadership.

Africa, in particular, has towering needs in several indus-tries including telecommunications, power, railways, and consumer goods. The construction market in Africa, for example, grew by 78 percent from 2008 through 2009. Of the top-ten construction companies in the African market, ? ve are from China, four are from the United States and Europe, and one is Brazilian. Three—China Communications Construction Company, Sinohydro, and Odebrecht Group—are global challengers.

Several regional and international retail chains are expanding into new markets in Latin America. Chile’s Falabella plans to open 180 stores and seven shopping malls by 2014, including two key projects in Peru. Mexico’s Femsa opened stores in Colombia in 2010 and plans to have 20 to 30 stores by 2012. Carrefour is also present in Colombia.

Domestic Duty. The global economic downturn encour-aged many companies headquartered in RDEs to refocus on their domestic markets. Domestic M&A deals by glob-al challengers increased 13 percent during the two years ending in August 2010, compared with the earlier two-year time period. (See Exhibit 7.)

These companies doubled down on their bets in the mar-kets they knew best because they recognized that many of the most promising growth prospects were close to home. Indeed, some companies have chosen to diversify into new domestic industries rather than expand their business globally.

A few companies have also reevaluated or postponed in-ternational expansion plans a er the recession exposed the vulnerabilities of international markets.

C M

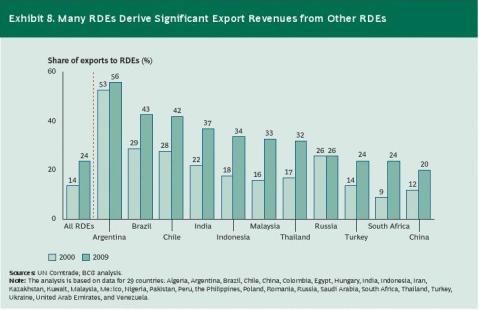

Trade-Led Globalization. The expansion of emerging markets is swelling trade volumes in the region. (See Ex-hibit 8.) Such countries as Brazil, Chile, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Russia now receive more than 25 percent of their export revenues from other RDEs. This rise in trade is straining the capacity of ports and shipping facilities. In Latin America, port capacity will need to double every ? ve years in order to accommodate increasing cargo tra? c. Container demand in Asia grew by an average of 12 percent annually from 2005 through 2009, compared with growth of 5 percent in other parts of the world. By 2015, the Asia-Paci? c region is expected to handle 68 percent of global tra? c, and intraregional container-trade volumes within Asia will be equivalent to the Asia-Europe and trans-Paci? c trade combined. In or-der to accommodate this growth, $51 billion in port-relat-ed infrastructure investments are required, according to the United Nations.

Global challengers are taking advantage of these trends. DP World of the United Arab Emirates has focused on emerging markets as a core strategy and is growing

50 percent faster than the industry average. Of its 50 ter-minals and 11 new developments and major expan-sions, 37 are in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. DP World plans to double capacity in line with market de-mand during the new decade to around 92 million TEU (an industry measure of container units), mostly in such emerging markets as Brazil, Egypt, India, Pakistan, and Turkey.

Rise of Many Cities. Growth in emerging markets is moving from megacities to midsize cities, where more than 80 percent of the RDE population lives. Revenues for consumer ? nance in emerging cities, for example, will likely total $10 trillion by 2030, with 65 percent originating in midtier cities. The same pattern will hold true for other industries, causing companies to rethink their sales and distribution strategies.

In Indonesia, tier 2 cities such as Samarinda have become the focus of global multinationals. Ford opened its ? rst dealership in Samarinda in 2007, and sales there have in-creased 30 percent over the past two years. Ford is plan-ning retail outlets in seven other tier 2 cities. In India,

T B C G

Tommy Hil? ger opened stores in ? ve cities in 2010 in-cluding Amritsar, Bhopal, and Dehradun. In China, retail giants Best Buy, Carrefour, and Wal-Mart are rapidly add-ing stores in midsize cities. The next frontier for retail in Latin America, meanwhile, is actually cities with fewer than 50,000 inhabitants—as larger cities are already reaching saturation.

These battles have implications for global challengers and established competitors alike. For challengers, they are the following:

? Choose carefully where to compete: domestic markets, in either existing or new businesses; developed mar-kets; or emerging markets.? Protect core home markets that may be vulnerable to attack from global multinationals and other global challengers. Take advantage of proximity to these mar-kets to develop more relevant products.? Create innovative business models to reach middle-class consumers in many cities or serve the growing cities themselves by providing infrastructure projects.? Consider acquiring skills and scale through partner-ships with other companies. Be aware of partnership opportunities with multinationals in local markets.? Adapt business models to move beyond the traditional bases of competitive advantage.The implications for established players are the fol-lowing:

? Understand the competitive advantages and cost struc-tures of the challengers and determine whether these advantages are waxing or waning as the structure of the industry shi s.

? Be clear about the customer segment you are target-ing. There is no single middle market but rather three

general subsegments: consumers trading down, con-sumers trading up, and consumers who serve as a sta-ble middle. ly to ? ght the challengers. ? Adapt business models swi

Localize product development and marketing—in most industries, “global” products will not cut it. Take advantage of the lower costs in developing markets. ? Reinforce the barriers that impede challengers by fo-cusing on traditional strengths in branding and R&D, but be prepared for the emergence of innovative and brand-savvy challengers. Identify ways to compete be-yond price.? Actively look for local partnerships, especially to dis-tribute and service products. Consider partnerships or acquisitions in RDEs. Closely scan companies in RDEs as potential customers and vendors.

C

ompetition between global multinationals and challengers will intensify in the new decade, with each side bringing its own strengths to bear. As

things evolve, the boundaries between these two distinct sets of companies will blur. In order to succeed in RDEs, global multinationals will need to adopt the practices of challengers—and vice versa. Increasingly, there will be a cross-pollination of ideas and practices.

Before the end of the new decade, the winning global companies will be identi? ed less by their home market and more by how they adapt to the fast-moving world in which they compete.

C M

For Further Reading

The Boston Consulting Group pub-

lishes other reports and articles that

may be of interest to readers of this

report. Recent examples include the

publications listed here.The Internet’s New Billion: Digital Consumers in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and IndonesiaA report by The Boston Consulting Group, September 2010The Keys to the Kingdom: Unlocking China’s Consumer PowerA report by The Boston Consulting Group, March 2010Threading the Needle: Value Creation in a Low-Growth Economy

A report by The Boston Consulting

Group, September 2010From Crisis to Opportunity: How Global Challenger Companies Are Seeking Industry Leadership in the Postcrisis WorldA White Paper by The Boston Consulting

Group, September 2009

Winning in Emerging-Market Cities: A Guide to the World’s Largest Growth Opportunity

The BCG 2010 Value Creators Report,

September 2010The 2009 BCG 100 New Global Challengers: How Companies from Rapidly Developing Economies Are Contending for Global Leadership

A report by The Boston Consulting

Group, January 2009The Global Infrastructure Challenge: Top Priorities for the Public and Private Sectors

A White Paper by The Boston Consulting

Group, July 2010

The African Challengers: Global Competitors Emerge from the Overlooked Continent

A Focus by The Boston Consulting Group,

June 2010

T B C G

Note to the Reader

This is BCG’s fourth report in the Global Challenger series. While the centerpiece of these publications is the list of 100 companies, the main purpose of the research and analysis is to understand the speci? c strate-gies and challenges of companies op-erating in RDEs and the evolution of those markets. Especially today, when developed markets are strug-gling to regain their momentum, these economies—and the compa-nies that make them so vibrant—are worth paying attention to.

Irina Gaida, Marcin Galczynski, Joerg Hildebrandt, Lisa Ivers, Melanie Jarzyniecki, Dorota Korenkiewicz, Tapan Kumar, Jean Le Corre, Yue Liu, Ayesha Malhotra, Marcela Rodrigues, Ratna Soni, Arvind Subramanian, Rahul Surve, Evelyn Tan, Burak Tan-san, Kanchanat U-Chukanokkun, Navneet Vasishth, Mark Voorhees, Felix Wagner, and Jony Yuwono. We would also like to thank our col-leagues Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Mary DeVience, Angela DiBattista, Elyse Friedman, Abby Garland, and Sara Strassenreiter for their contributions to the editing and production of this publication.

Kanika SanghiProject LeaderBCG Mumbai+91 22 6749 7000

sanghi.kanika@bcg.comHolger Michaelis

Partner and Managing DirectorBCG Beijing

+86 10 8527 9000

michaelis.holger@bcg.comPatrick Dupoux

Partner and Managing DirectorBCG Casablanca+33 140 17 10 10

dupoux.patrick@bcg.comDinesh Khanna

Partner and Managing DirectorBCG Singapore+65 6429 2500

khanna.dinesh@bcg.comPhilippe Peters

Partner and Managing DirectorBCG Moscow+7 495 258 34 34

peters.philippe@bcg.com

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the execu-tives of the global challenger compa-nies who agreed to be interviewed for this report. These interviews pro-vided valuable insights into the glob-al challengers’ strategies, ambitions, and challenges and deepened our understanding of these companies.The research and analysis that went into this report were conducted by a global team of BCG consultants who were based primarily in RDEs around the world and worked under the di-rection of Kanika Sanghi. The team also had the support of senior BCG advisors in both RDEs and developed markets.

We also thank the following col-leagues for their contributions: Neeraj Aggarwal, Anand

Veeraraghavan, Markus Brummer, Marcela Burgos, Chirag Chavda, Silmara Costa, Deepak Deshmukh, Khushnuma Dordi, Irina Egorova,

C M

For Further Contact

This report was sponsored by the Global Advantage practice. For information about the activities of the practice, please contact: Andrew Tratz

Global Manager, Global Advantage Practice

BCG Beijing

+86 10 8527 9000

tratz.andrew@bcg.com

If you would like to discuss our obser-vations and conclusions, please con-tact one of the authors, listed below:Sharad Verma

Partner and Managing DirectorBCG New Delhi+ 91 124 459 7000

verma.sharad@bcg.com