本科生毕业论文(设计)

题 目 ××××

学 院 经济学院

专 业 ××

学生姓名 ××

学 号 ×× 年级 2××级

指导教师 陈小凡

教务处制表

二ΟΟ × 年 五 月 十五 日

试述我国资本账户开放

专业:金融学

学生:×× 指导老师:陈小凡

摘要:开放资本账户,是一国从封闭型经济转变为开放型经济的决定性步骤。资本账户的完全开放,既标志着该国的经济金融已完全融入国际社会,实现了彻底的国际接轨,也意味着该国经济和金融运行机制与运行格局要再退回到资本账户开放前的状态已极为困难了。因此,对任何国家(或地区)来说,是否开放资本账户都是一项重大的具有深远影响的经济决策。而在东南亚金

关键词:外汇管制 经常账户开放 资本账户管制 资本账户开放

Take a glance at the opening of domestic capital accounts

Major: Finance

Student: ×× Supervisor: Chen Xiaofan

Abstract: The opening of the capital account is a decisive step to a country transforming from close economy to an open economy. It indicates not only this country has integrated the international society,but also it is difficult for country to return previous status. Therefore,to any country or area, it is an importantly economic decision whether to open the capital account. And this topic has become more and more sensitive after the southeast financial storm. Under the circumstance whether our country will continue the process of the convertibility of RMB and how to continue have became a focus concerned

Key words: Exchange control; Current Account open up; Capital Account control; Capital Account open up

目 录

0.导言. 5

1. 资本账户开放概述. 8

1.1 资本管制. 8

1.1.1 资本管制限制了投机性的短期资本流动,从而稳定了外汇市场. 8

1.1.2 资本管制可以维持国内税基的稳定. 9

1.1.3资本管制可以保持国内储蓄. 9

1.1.4 资本管制能够帮助保持国内经济稳定及推动国内经济结构的调整. 9

1.2 资本账户开放的涵义. 9

1.2.1关于资本账户开放的一些定义. 9

1.2.2在具体把握资本账户开放的内涵时,应注意的几点问题. 10

2. 开放资本账户的利弊分析. 11

2.1 开放资本账户的收益. 11

2.1.1争取外国私人资本、解决自由资金不足. 11

2.1.2缓解货币升值的压力,促进宏观经济和金融的稳定. 11

2.1.3资本的自由流动将促进金融服务的专业化生产. 12

2.1.4资本账户的开放将为一国的金融部门带来动态经济利益. 12

2.2 开放资本账户的风险. 12

2.2.1很可能出现实际汇率升值,严重损害一国的实际经济部门. 12

2.2.2货币政策独立性和汇率稳定之间会发生冲突. 12

2.2.3资本项目可兑换冲击发展中国家经济和金融体系. 13

2.2.4开放资本项目带来一定的负面影响. 13

2.2.5增加了平衡国际收支的难度. 13

3. 我国资本账户开放的政策建议. 14

结语. 23

参考文献:. 24

附录1 主要英文参考文献原文:. 25

附录2 主要英文参考文献译文:. 36

致谢. 43

0 导 言

0.1 研究背景和意义

国际金融交易与国际资本流动的增长是二十世纪末影响最为深远的经济发展之一,实现货币自由兑换是世界经济一体化的必然要求。为了能够充分利用国际金融流动显著增长带来的机遇,越来越多的国际货币基金组织成员国取消了对资本项目交易的限制。我国于1996年12月1日实现了人民币经常项目下的可兑换,取消了对经常性国际支付和转移的限制,达到国际货币基金组织第八条款规定的标准。

0.2 文献综述

0.2.1 国外研究现状

国外对资本项目开放的研究大致可分为三种观点,即永久性资本管制、分阶段放松资本管制和激进的资本项目自由化改革。

Mckinnon(1993)指出:国际收支资本项目的开放应是改革一揽子计划中的最后一步。只有进行成功的财政改革和国内金融市场的自由化,才可以对对外经济部门进行改革。这种[3]

Qwirk(1990)年阐述了资本控制无效论。认为如果一国已实现了经常项目的自由化,就不可能有效控制资本项目,大量的资本外逃不可避免,管制成本也变得很大。[4]注意根据文献在正文中出现的顺序,在后面的参考文献中排序,并将序号在正文中以上标形式反映

0.2.2 国内研究现状

陈彪如(1983)认为:人民币自由兑换是我国经济发展的必然要求,人民币最终将成为国际货币。[6]

实现人民币可兑换课题组(1993)年指出:放松资本管制具有一定的必要性并能带来好处,但这些潜在的利益转化为现实的利益是需要一些外部条件的,到目前为止,对这些条件的分析尚不充分。[7]

姜波克(1999)认为:在我国经济体制还没有完成市场化的转变过程、宏观调控还不健全的条件下,一旦放松资本项目的管制或急于达成资本项目的可兑换,很可能会出现资本逃避、货币替代、大量资本流入等问题。[8]

渐进改革的观点反映了国内改革的主流思想,认为中国必须实现资本项目的可兑换,但这一目标的实现有赖于国内其它各项改革的顺利推进。迄今为止,完全实现的资本项目可兑换的条件尚未成熟,资本项目开放只能分步进行。

0.3 写作思路

本文综合运用宏观经济学、国际金融学和国际经济学的理论围绕资本项目的管制问题进行探讨。首先,阐述了资本项目管制以及资本账户开放的定义;然后,分析了开放资本账户

1资本账户开放概述

资本账户(capital account)又称“资本项目”,是国际收支平衡表中重要的组成部分。根据《中华人民共和国外汇管理条理》,资本账户是指国际收支中因资本输出和输入而产生的资产负债的增减项目,包括直接投资、证券投资、各类贷款等。除了在某些细节方面有所区别外, 基本上与国际通行的惯例相一致。国际货币基金组织所指的资本项目下可兑换,指的是“消除对国际收支资本和金融账户下各项交易的外汇管制,如数量限制、课税及补贴”。开放资本账户,是一国从封闭型经济转变为开放型经济的决定性步骤,标志着该国的经济金融已完全融入国际社会,彻底实现了国际接轨。

1.1 资本管制

资本管制是外汇管制的一个重要方面,外汇管制(Exchange Control or Exchange Restriction),又称外汇管理(Exchange Management),是指一国政府通过法律、法令以及行政措施对外汇的收支、买卖、借贷、转移以及国际间结算、外汇汇率、外汇市场和外汇资金来源与应用所进行的干预和控制[1]。而资本管制则是一国对其资本账户项目交易的管制,包括对储备资产、直接投资、间接投资(证券投资)和其他资本交易的管制。对资本账户管制的措施包括:对资本流动实际外汇管制或数量限制;双重或多重汇率安排;以及向对外金融交易征税。[9]

1.1.1资本管制限制了投机性的短期资本流动,从而稳定了外汇市场

在浮动汇率制度下,管制资本流动的情况取决于金融部门与实际部门不同的调整速度。当名义汇率对出清的资本市场即刻反映时,实际经济部门则要经过缓慢的调整,例如实际工资的粘性,投资决策的不可撤消性。托宾和多恩布什认为,这种调整速度的不一致性加上金

1.2 资本账户开放的涵义

1.2.1 关于资本账户开放的一些定义[d1]

资本账户开放,也称资本账户可兑换。对于资本账户开放或可兑换,包括基金组织在内的国际组织对它没有统一的标准定义。目前,对资本账户开放定义主要有两类方法:一类是广义定义。如基金组织专家Quirk和Evans(1995),将可兑换表述为取消对跨国界资本交易的控制、征税和补贴[11];中国外汇管理局的管涛(2001),则将其定义为避免对跨国界的资本交易及与之相关的支付和转移的限制,避免实行歧视性的货币安排,避免对跨国资本交易征税或补贴[12]。

2 开放资本账户的利弊分析

许多发展中国家经历了各自的资本账户开放过程,放松资本账户管制使国际资金流入,支持了国内经济的增长;但如果国内经济出现问题,国际资金的趋利弊害的动机,会导致资金的大进大出,给一国的经济带来巨大的冲击。所以说,开放资本账户是一把“双刃剑”。

2.1 我国资本账户管理现状及评价

2.1.1 我国资本账户管理现状

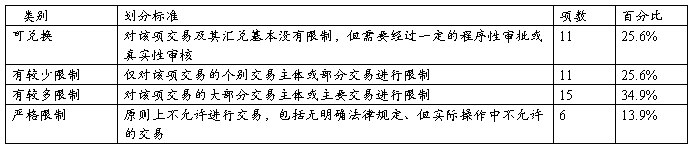

按照“循序渐进、统筹规划、先易后难、留有余地”的改革原则,中国逐步推进资本项目可兑换。20##年底,按照国际货币基金组织确定的43项资本项目交易中,我国有11项实现可兑换,11项较少限制,15项较多限制,严格管制的仅有6项,见表1。

表1 中国资本账户管制按管制程度分类

资料来源:国家外汇管理局 中国外汇管理年报2004。

结语

总之,对于我国这样一个正处于复兴中的发展中国家,对待资本账户的开放一定要谨慎。西方发达国家的历史进程告诉我们,开放资本账户是历史的必然;历史也同样告诉我们如果不采取正确的开放时间和措施,就会对一国经济带来莫大的冲击和破坏。我国现在要做的就是根据我国现阶段管制的现状,特别是我国的国情,谨慎采取一定的模式不仅可以使我国完成资本账户开户,同时也有利于减小在这一过程的风险。

参考文献:

[1] Edwards.S. The order of liberalization of the external sector in developing countries. Princeton Essay in International Finance. 1990(8): 31-44

[2] James A.Hason.Open the Capital Account: Costs, Benefits, and Sequencing, in Sebastian Edwards,ed.Capital Controls, Exchange Rates and Monetary Policy in the World Economy, New York:Cambridge University Press.1997

[3] Mckinnon. The Order of Economic Liberalization-Financial Control in the Transition to a Market Economy. Baltimore and London:The John Hopkins University Press, 1991:215-234

[4] Quirk.Peter ,Owen Evans. Capital Account Liberalization of developing country.

IMF Occasional Paper.1995(11):24

[5] R.Barry Johnston.Salin M.Darbar, and Claudia Echeverria. Sequencing Capital Account Liberalization:Lessons from the Experiences in Chile, Indonesia,korea and Thailand, IMF Working Paper.1997

[6] 陈彪如.迈向货币的自由兑换.国际金融专题研究.1983(4): 7-16

[7] 实现人民币可兑换课题组.人民币走向可兑换.改革.1993(8): 11-1

[8] 姜波克.人民币可兑换与资本管制.上海:复旦大学出版社.1999:8

[9] 杨胜刚、姚小义.国际金融.20##年版.湖南:湖南大学出版社

[10] 易宪容.本账户开放的理论与运作,中国社会科学院国际金融研究中心 2001-09

[11] 货币基金组织.资本账户自由化:经验和问题 国际货币基金组织不定期刊物,中国金融出版社.1995

[12] 管涛.资本项目可兑换的定义.经济社会体制比较,2001-01

[13] 胡晓炼.人民币资本项目可兑换问题研究.中国外汇管理.2002-04

[14] 郑昕.试论资本账户开放.浙江师范大学.2005-5-31

[15] 邬小蕙.资本账户开放问题研究.首都经济贸易大学 2002-03-01 万方论文网

[16] 张霞.对我国资本项目开放问题的研究.山西财经大学.万方论文网.2003-4-20

[17] 王静.论中国资本项目开放对外经济贸易大学.万方论文网.2003-05-01

[18] 曾超.逐步放松资本项目管制的研究.华中科技大学.万方论文网.2002-11-8

[19] 徐杰.中国资本账户开放的现状及前景 .行政与法.2004-05

[20] 庞锦.资本账户开放的模式选择.南方金融.2000-09

[21] 中国外汇管理年报.国家外汇管理局.2004

[22] 吴静静.发展中国家资本账户开放研究及中国的策略.西南财经大学.万方论文网.2001-4-1

[23] Ronald I. McKinnon.China's New Exchange Rate Policy:Will China Follow Japan into a Liquidity Trap?.Weekly Economist.2005-10

[24] 姜波克,邹益民.人民币资本账户可兑换问题研究.上海金融.2002

附录1 主要英文参考文献原文:

China's New Exchange Rate Policy:

Will China Follow Japan into a Liquidity Trap?

By Ronald I. McKinnon

Stanford University

On July 21, 2005, China gave in to concerted foreign pressure-some of it no doubt well meant-to give up the fixed exchange rate it had held and grown into over the course of a decade. China's exchange rate had been successfully fixed at 8.28 yuan per dollar within a narrow range of plus or minus 0.3 percent with no restraints on the renmibi's value against non-dollar currencies. With this exchange rate anchor for its monetary policy, inflation declined and China's extraordinarily high real growth became more stable. However, the U.S. Congress had threatened, and still threatens, to pass a bill that would impose an import tariff of 27.5 percent on Chinese imports unless the renminbi was appreciated, and pressured the U.S. Administration to retain China's legal status as a "centrally planned" economy (despite its wide open character) so that other trade sanctions-such as anti-dumping duties could be more easily imposed.

The Chinese authorities also announced on July 21 that they would allow greater exchange rate flexibility for the renminbi against a basket of currencies, in which the dollar would only be one of several currencies including the euro, the yen, the pound sterling, the won, the ruble, and so forth. However, they did not announce what the weights of these foreign currencies would be. Basket pegging is particularly favored by Japanese economists who want the yen be more heavily represented in the currency baskets of other East Asian economies. But, as we shall see, basket pegging is an idea that is ill defined and not sustainable.

Currency baskets aside, the probability of future appreciation of the renminbi against the dollar has become greater since the People's Bank of China abandoned its traditional "parity" rate of 8.28. True, the actual appreciation against the dollar since July 21 of the still tightly controlled renminbi has been trivial-less than 3 percent. And it is much less than the 20 to 25 percent appreciation called for by vociferous American critics of China's foreign exchange policy. But the move signaled that further appreciations had become more likely in the guise of achieving greater exchange rate flexibility.

American pressure on China today to appreciate the renminbi is earily similar to the American pressure on Japan that began almost 30 years ago to appreciate the yen against the dollar. There are some differences between the two cases, but down-war pressure on interest rates from foreign exchange risk could lead China into a zero-interest liquidity trap much like the one Japan has suffered since the mid-1990s.

1 From Japan to China Bashing

To understand the origins of the foreign exchange risk that could eventually lead to a zero-interest-rate trap, consider first the earlier mercantile interaction between Japan and the United States, and then the recent trade disputes between China and the U.S. shows that Japan's bilateral trade surplus, largely in manufactures, with the United States began to grow fast in the mid-1970s, peaked out at about 1.4 percent of U.S. GNP in 1986, and remained substantial subsequently. Somewhat arbitrarily, I demarcated the period of intense "Japan bashing" by many Americans and Europeans as falling between 1978 and 1995. "Japan bashing" came to mean the continual threat of U.S. trade sanctions on Japanese exports unless Japan ameliorated competitive pressure on impacted American industries. Typically, these trade disputes were resolved by Japan's agreeing to serially impose temporary export restraints on steel, autos, televisions, machine tools, semiconductors, and so on, coupled with allowing the yen to appreciate. Indeed, the yen did appreciate episodically all the way from 360 to the dollar in 1971 (just before the Nixon shock) to 80 to the dollar in April 1995.

By 1995, the Japanese economy had become so depressed by the overvalued yen , that the Americans relented and Secretary of the Treasury Robert Rubin announced a new "strong dollar" policy. The U.S. Federal Reserve Bank jointly intervened with the Bank of Japan several times in the spring and summer of 1995 to stop the yen's going ever higher. Since then, the yen has fluctuated widely (perhaps too much so), but has never again gone so high as 80 to the dollar-and Japan bashing more or less ceased.Nevertheless, Japan has still not fully recovered from its lost decade of the 1990s.

Now China bashing has superseded Japan Bashing. China's bilateral trade surplus with the United States was insignificant in 1986, but then began to grow much more rapidly than Japan's after 1986. By 2000, figure 1 shows that China's was as large as Japan's bilateral surplus, and by 2004, it was twice as large. However, Japan, with its still much bigger economy in 2004, had an overall current account surplus (measured multilaterally) of US$172 billion and China's was "only" US$70 billion. Nevertheless, a large and growing bilateral trade surplus concentrated in competitive manufactures with the United States has triggered U.S. threats of trade sanctions and demands for currency appreciation-pressure that China had felt for a least four years before giving in last July.

Interestingly, in Japan's great high-growth era of the 1950s and 1960s, its manufactured exports to the United States grew even more rapidly than in subsequent decades, much like China's today. But back then, Japan had roughly balanced trade (no saving surplus) with the rest of the world. Because Japan's imports of both primary products and manufactured goods, many from the United States, also grew rapidly, Americans broadly tolerated rapid increases in manufactured imports from Japan. Painful restructuring in American import-competing industries were offset by export expansion, often in manufacturing. So pressure for net contraction in American manufacturing was minimal because there was no overall American current account deficit.

However, the situation changed dramatically in the late 1970s and 1980s when the U.S. first began to run large overall current account deficits-including large bilateral trade deficits with Japan (figure 1). These overall deficits were widely attributed to an American saving shortage from large U.S. fiscal deficits: the famous twin deficits of the era of President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Heavy U.S. international borrowing, largely from Japan, could only be transferred in real terms by the United States' running a deficit in tradable goods or services-and Japan's principal export was manufactures. America ran a large trade deficit in manufactures, leading to a net contraction in the size of its manufacturing sector. Because political lobbies in American import competing sectors hurt by Japanese competition became stronger than those in the shrinking export sector, Japan bashing became more intense in the 1980s before peaking out in 1995.

In the new millennium, China's emergence as a major trading nation has coincided with a new round of war-related deficit spending by the U.S. federal government, and surprisingly low personal saving by American households-perhaps because of the bubble in U.S. residential real estate. This American saving deficiency results in an enormous overall current-account deficit of about 6 percent of American GDP in 20## and 20##-much bigger then the combined current account surpluses of Japan and China.

Rather than a saving deficiency in the United States, the alternative, or perhaps complementary, theory is that there is a saving glut in the rest of the world-not only in East Asia but increasingly in oil-producing countries in the Middle East and elsewhere (Bernanke, 2005). Indeed, Zhou Xiaochuan, Governor of the People's Bank of China, has stressed that the best way to bring down China's overall (multilateral) current account surplus is to increase consumption in China itself. But most East Asian countries have current account (saving) surpluses-some of which are a larger proportion of their GNPs than is China's. Whether the problem is a saving deficiency in the United States, or a saving glut elsewhere, or both, the result is a substantial widening of the American trade deficit in manufactures-for which there is no exchange rate solution, as we shall see.

Why then is China bashing in the U.S. now so much more intense than Japan bashing or Germany bashing when the latter two countries still have larger manufactured exports and larger overall current account surpluses than China's? Because of the idiosyncratic way in which world trade, and Asian trade in particular, is organized, China's bilateral trade surplus with the United States is bigger and more noticeable to American politicians. Virtually all East Asian countries today have overall current account surpluses, and several have bilateral trade surpluses with China. China buys high- tech capital goods and industrial intermediate inputs from Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and European countries such as Germany-and also buys raw materials from many sources in Asia, Latin America, Africa, and elsewhere. China then transforms these inputs into a wide variety of middle-tech manufactured consumer goods for the U.S. market. Many of China's exports are from final processing industries, where valued added per good produced in China itself isn't high because many of the components come from Asian neighbors and elsewhere.

However, Americans see the proliferation of "Made in China" labels in the huge influx of imported of finished consumer manufactures, and American politicians myopically blame China for being an unfair competitor. But China is merely the leading edge of a more general, albeit somewhat hidden, East Asian export expansion into the United States-which in turn reflects very high savings rates by Asians collectively and abnormally low saving by Americans.

2 Selective Restraints on Exports

China bashing today primarily takes the form of pressuring China to appreciate its currency, or to let the yuan/dollar rate be more "flexible". China's ongoing accumulation of dollar claims from its trade surplus and inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) would lead to an indefinite upward spiral in the renminbi if it was floated.

By contrast, in the earlier 1978-95 period of Japan bashing, American demands for a general appreciation of the yen were often coupled with the demand that Japan impose "voluntary" restraints on exports of particular products. Because past waves of Japanese exports into the world and American markets were successively concentrated in heavy industries- such as steel, autos, televisions, semi-conductors, and so on- it made sense to soften the impact on different American import-competing industries by temporarily restricting Japan's export growth in these particular products. American industrial lobbies in heavy industries were concentrated and politically potent.

In contrast, recent Chinese exports into the American market have been low to middle tech products of light industry. Rather than being concentrated in particular heavy industries, they are spread across the board, and protectionist lobbies for specific industries in the United States are not so ardent as in the earlier Japan-bashing campaigns. The one big exception is textiles and apparel, where China's position has been complicated by the expiration on January 1, 2005, of the international multi-fiber agreement (MFA) that had limited Chinese textile exports into world markets. However, as a matter of practical politics for relieving foreign distress, China could voluntarily, but temporarily, re-impose constraints on its own textile exports through tariffs or quotas-as per Japan's earlier restraints on its exports-although neither were (are) legally obligated to do so.

3 The Exchange Rate and the Trade Balance

Although temporary restraints on particular export products, whose rapid growth disrupts markets in importing countries, are all well and good, America's demand that China appreciate its currency against the dollar is as unwarranted now as was the earlier pressure on Japan to appreciate the yen. A sustained appreciation of a creditor country's currency against the world's dominant money is a recipe for a slowdown in economic growth, followed by eventual deflation, as Japan found to its sorrow in the 1990s. But the net effect on its trade surplus is indeterminate.

Nevertheless, a reading of the recent financial press and writings of many influential economists on both sides of the Pacific Ocean suggests that a major depreciation of the dollar is needed to correct the current account and trade deficits of the United States. For this purpose, they argue, East Asian countries should stop pegging their currencies to the dollar. Especially China should substantially appreciate the renminbi and then move to unrestricted floating.

This mainstream view rests on two crucial presumptions. The first is that an appreciation of any Asian country's currency against the dollar would significantly reduce its trade surplus with the United States. The second is that a more flexible exchange rate is needed to fairly balance international competitiveness. But under the regime of the international dollar standard, neither presumption holds empirically. Consider the effect of the exchange rate on the trade balance first.

If a discrete exchange rate appreciation is to be sustained, it must reflect relative monetary policies expected in the future: relatively tight money and deflation in the appreciated country and relatively easy money with inflation in the country whose currency depreciates. There are three channels through which this necessarily tighter monetary policy imposes deflationary pressure in a creditor economy that appreciates.

First, there is the effect of international commodity arbitrage. An appreciation works directly to reduce the domestic currency prices of imported goods whose world market prices are more or less fixed in dollars. (The pass-through effects of an exchange rate change for countries on the periphery of the dollar standard are much stronger than in the United States itself.) And because domestic exports are seen to be more expensive in foreign exchange, the fall in foreign demand for them directly bids down their prices measured in the domestic currency. This fall also indirectly reduces domestic demand elsewhere as the export and import-competing sectors contract.

Second, there is a negative investment effect. A substantial appreciation makes the country look like a more expensive place to invest, particularly in export or import competing activities. This applies strongly to foreign direct investment (FDI) as well to purely national firms looking to compete in foreign markets. Even foreign investment in domestic non-tradables, service activities of many kinds, will be somewhat inhibited because most potential foreign investors are capital constrained. That is, they are limited by their equity positions or net worth-and an exchange rate appreciation will require more equity in dollars to buy any given amount of domestic physical capital. The upshot is that, in the country with the newly appreciated currency, investment slumps.

Third, there is a negative wealth effect from being an international creditor with net dollar assets. Because these dollar assets lose value in terms of the domestic currency, the deflationary impact of an exchange appreciation is accentuated. This negative wealth effect further reduces domestic consumption as well as investment and aggravates the slump (growth slowdown) in the domestic economy.

So we have three avenues through which the impact of an appreciation reduces domestic spending and sets (incipient) deflation in train within a creditor country holding dollar assets. The resulting fall in aggregate domestic demand also reduces the demand for imports even though imports have become cheaper. True, the relative price effect of an appreciation also makes domestic exports more expensive to foreigners, so exports decline. But the fall in imports could be sufficiently strong so as to leave the net trade balance indeterminate theoretically7. For example, when Japan was cajoled (forced) into appreciating the yen several times from the mid-1980s into the mid-1990s, it was thrown into a decade-long deflationary slump with no obvious decline in its large trade surplus measured as a share of its GNP.

4 The Exchange Rate as Monetary Anchor

Beyond wanting to "adjust" the trade balance, many economists and commentators in the financial press-including such heavyweights as the International Monetary Fund-also argue for exchange rate flexibility in order to insulate domestic macroeconomic policy from the ebb and flow of international payments. The IMF advises China to make its exchange rate more flexible in order increase its "monetary independence," particularly from the United States. But is this good advice for a rapidly growing developing country whose financial system is still immature?

Outside of Europe, the dollar is the prime invoice currency (unit of account) in international trade in goods and services. All primary products-industrial materials, oil, food grains, and so forth-are invoiced in dollars. A few mature industrial countries invoice some of their exports of manufactured goods and services in their own currencies. But even here, the international reference price of similar manufactures is seen in dollar terms. So manufacturers throughout the world "price-to-market" in dollars if they can. Because most East Asian countries invoice their trade in dollars, these countries collectively are a natural dollar area. Japan is the only Asian country that uses its own currency to invoice some of its own trade. Even here, almost half of Japan's exports and three-quarters of its imports are in dollars. But when China trades with Korea, or Thailand with Malaysia, all the transactions are in dollars.

For three closely related reasons, each East Asian country has a strong incentive to peg to the dollar, either formally or informally, thus hitching its monetary policy to that of the center country.

First, as long as the purchasing power of the dollar over a broad basket of tradable goods and services remains stable, as it has from the mid-1990s to the present, then pegging to the dollar anchors the domestic price level. The extent of dollar-invoiced trade among neighbors in East Asia is now much greater than trade with the United States itself. Thus the anchoring effect for any one country pegging to the dollar is stronger because East Asian trading partners are also pegging to the dollar.

Second, East Asian countries are strong competitors, particularly in manufactures, in each other's markets as well as in the Americas and Europe. No one East Asian country wants its currency to appreciate suddenly against the world's dominant money. This would lead to a sharp loss in mercantile competitiveness in export markets, followed by a general slowdown in its economic growth, followed by outright deflation if appreciation continued.

Third, domestic financial markets in a high-growth developing country such as China now, or Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, exhibit both rapid transformation and incomplete liberalization. In China's immature bank-based capital market, domestic money growth is high and unpredictable, while many interest rates remain officially pegged. Thus the People's Bank of China (PBC) cannot rely on observed domestic money growth or interest rates as leading indicators of whether monetary policy is being too tight or too easy. Whence the importance of relying on an external monetary anchor-360 yen/dollar in the 1950s and 60s for Japan, and 8.28 yuan/dollar from 1995 to July 21, 20## for China-as a benchmark for the national monetary (and fiscal) authorities. To secure their well-defined exchange rate target, the authorities can then use a range of ad hoc administrative controls over bank credit, reserve requirements, limited interest rate adjustments, and sterilization of the monetary impact of accumulating official exchange reserves. The incidental or indirect effect is then to stabilize the domestic price level.

However, this external monetary benchmark was not useful in the earliest stages of China's transition to a market economy. After 1978, China began gradually to dismantle internal price controls but left restrictions on foreign trade largely intact- except for a few special economic zones. For almost a decade and a half afterward, the economy was not generally open to free international commodity or financial arbitrage. Foreign trade was organized by state trading companies that (tried to) insulate domestic from foreign relative prices independently of the exchange rate-the so called air lock system. Indeed, beginning at the overvalued but meaningless level of about 1.7 yuan per dollar in 1978, the renminbi was devalued several times in the 1980s to reach 5.5 yuan per dollar in 1992 without much impact on domestic prices. The exchange rate was not, and could not be, an anchor for domestic monetary policy and the price level in this early phase of China's financial transformation.

In effect, before 1994, China was following a national monetary policy that was largely independent of the foreign exchanges. Gregory Chow (2002, ch.7) documents how the Chinese lost monetary control and over issued domestic money in 1984, 1988-89, and 1993-94. Thus domestic price inflation followed the roller coaster ride without any smoothing effect coming through the foreign exchanges. This early Chinese experience with highly variable rates of inflation illustrates how difficult it is for a very high growth economy to stabilize its national price level independently.

In 1994, however, China unified its exchange rate regime and moved toward current account convertibility in international payments for exporting and importing. (In 1996, China formally accepted Article VIII of the International Monetary Fund defining currency account convertibility. But the process was well begun before then.). This new regime now permitted direct price arbitrage in markets for internationally tradable goods and services. All well and good. But in unifying its official exchange rate with so-called swap-market rates, the PBC devalued the official rate too much-from 5.6 to 8.7 yuan/dollar, where 8.7 was the previous swap market rate (figure 3). This large, although somewhat accidental, depreciation then aggravated the burst of inflation over 1994-96. Figures 2 and 3 show that the CPI increased more than 20 percent in 1995-a penalty for over depreciating the exchange rate in the post-1994 regime of greater economic openness.

However, from 1995 to July 21, 2005, the Chinese authorities held the now-unified exchange rate constant at 8.28 yuan/dollar (plus or minus 0.3 percent). For these 10 years, they subordinated domestic monetary and fiscal policies to maintaining the fixed exchange rate-including not devaluing in the Asian crisis of 1997-98 when they came under great pressure to do so. They also further dismantled tariffs and quotas on imports faster than their WTO obligations required.

This move to greater economic openness, coupled with the fixed nominal exchange rate, ended the roller coaster ride in China's domestic inflation. Using four different measures of domestic inflation, Figure 2 shows the inflation slowdown in China's after 1996. Not coincidentally, figure 3 shows the convergence of inflation in China's CPI to that experienced by the United States-now the nominal anchor. So far in 1995, China's CPI increased less than 2 percent year over year. (In 2004, a substantial blip in primary commodity prices including oil was not fully passed through to the retail level.) In the new millennium, this international monetary anchor of a fixed exchange rate greatly helped China stabilize its domestic price level compared to its earlier "roller coaster ride".

But more was involved than just stabilizing inflation in China. Figure 4 shows that, after 1994, China's very high growth in real GDP also became more stable. No doubt that other explanations of the end of China's roller coaster ride in both inflation and real growth rates are possible. However, the data are consistent with my hypothesis that fixing the nominal exchange rate provided the much needed anchor. (The downside, of course, would be if the United States itself lost monetary control and inflated too much. And the U.S, Federal Reserve Bank did seem to be too easy, i.e. kept interest rates too low, in 20## into 20##-but seems to be recovering in late 2005.)

Behind the scenes in this remarkable convergence of Chinese to American rates of price inflation is the high rate of growth in money wages in China. In China's "catch up" phase, where the level of output per person is much less than in mature industrial economies, growth in productivity per worker is naturally very high. However, as long as money wages grow very fast to reflect this productivity growth, currently 10 to 12 percent per year, then international competitiveness remains balanced. And this is what happened in China in the past 10 years, and in Japan in its fixed exchange rate period from 1950 to 1970. As long as the nominal exchange rate remains securely fixed, then wage growth in the peripheral country naturally tends to track productivity growth in the most open tradable sector, i.e., manufacturing for China now and for Japan back in its 1950s and 1960s.

This high growth in money wages, reflecting high productivity growth, then secures the convergence of the rate of inflation in the peripheral country to that in the center country and secures the sustainability of the fixed exchange rate. But if the exchange rate appreciates and future appreciation seems more likely, then employers in the tradables sector will bid more cautiously for workers so money wage growth slows below the rate of productivity growth. This slowdown in wage growth then becomes integral to the general deflationary pressure arising from anticipated exchange appreciation-as in Japan from the mid-1980s into the 1990s.

5 A Liquidity Trap for China?

Partly arising out of codicils to the accord that secured China's entry into the WTO, financial liberalization remains an important objective of China's government. "Liberalization" has both an internal and external dimension. The government wants to move toward the decontrol of domestic interest rates, particularly on bank deposits and loans. Then, with freer interest rates, a more robust domestic bond market at different terms to maturity can be established. Eventually, the liberalization of capital controls in the balance of payments will permit a more active forward market for hedging foreign exchange risk to develop.

These are important and laudable objectives for improving the efficiency of China's capital markets in the long run. Now, however, with China's economy threatened by ongoing appreciation of the renminbi, liberalizing the financial system could have perverse short-run consequences. In the face of undiminished foreign exchange risk, i.e., the probability that the renminbi could appreciate, a near zero interest rate liquidity trap is possible-even likely. Figure 4 shows China's interbank interest rate in mid-2005 falling toward 1 percent even as the U.S. federal funds rate (coming off all time lows) rose to 3.5 percent. Although the PBC still pegs bank deposit and some loan rates, China's interbank interest rate is fairly freely determined. (Japan's short-term interest rate being stuck close zero since 1996: the dreaded liquidity trap.)

The basic problem is one of achieving portfolio balance between the holding of dollar and renminbi interest-bearing assets. In a liberalized capital market, investors must be compensated by a higher interest rate on dollar assets because of the risk that the renminbi might appreciate. But interest rates on dollar assets are given in world markets independently of what China does. Thus, the only way in which the market can establish the necessary interest differential is for interest rates on renminbi assets to fall below their dollar equivalents. If interest rates on renminbi assets don't fall immediately, then short-term capital ("hot" money) flows into China as investors try to switch their dollars into renminbi. The resulting upward pressure for exchange appreciation then forces the PBC to enter the foreign exchange market and buy the dollars to avoid an upward spiral. The huge buildup of dollar foreign exchange reserves, now almost US$800 billion, and consequential internal expansion of the domestic monetary base then drives down domestic short-term interest rates-at least until they hit zero.

Notice that just letting the renminbi float upward, or appreciate discretely, does not resolve the dilemma. Indeed it worsens it. Actual appreciation would lead to actual deflation with further downward pressure on domestic interest rates. From Japan's earlier experience of an erratically appreciating yen, we know that interest rates on yen assets were compressed toward zero in the ensuing deflation. And since actual appreciation need not reduce China's trade surplus, American pressure on China to appreciate further would only continue-as it did on Japan before 1995.

The first-best solution is to fix China's exchange rate in a completely credible way so that there is no fear of currency appreciation. Then financial liberalization could proceed with market interest rates remaining at normal levels, i.e., close to world or American rates. But the recent abandonment of China's "traditional parity" of 8.28 yuan per dollar, which it had held for 10 years, makes a new credibly fixed exchange rate strategy more difficult-and certainly not possible for some time.

Failing this, the second-best solution is for China to continue, and possibly strengthen, its foreign exchange restrictions on liquid financial inflows-thus limiting the foreign pressure to drive interest rates down. In addition, the PBC may have to continue to peg some bank interest rates on both deposits and loans above the relatively free interbank rate of interest. Unless lending rates remain comfortably above zero, normal bank profit margins cannot be maintained.

The prolonged experience of Japan from the early 1990s to the present, with interest rates compressed toward zero, was to sharply reduce the normal profit margins of commercial banks. This made it virtually impossible for them to work off old bad (nonperforming) loans, and they became reluctant to extend new bank credits-thus deepening Japan's slump in the 1990s.

6 Conclusion: A Slowdown in Financial Liberalization?

Unfortunately, the unhinging of China's exchange rate as of July 21, 20## must slow progress in liberalizing China's financial markets if it is to avoid falling into a Japanese-style liquidity trap. By "slowdown", I mean retaining capital controls on inflows of highly liquid "hot" money from dollars into renminbi, and continuing to peg certain interest rates such as basic deposit and loans rates in China's banks-in order to better preserve their profitability. This slowdown is, of course, an unfortunate detour from China's remarkable progress toward a market economy. Financial liberalization can be all well and good provided that no uni directional exchange rate change is threatened or in prospect.

If China does fall into a zero interest rate trap like Japan before it, then the PBC, like the BOJ, will be unable to offset deflationary pressure in the economy should a large exchange appreciation actually occur. The ongoing threat of further appreciation would continue because, contrary to popular opinion, China's trade surplus need not diminish as its currency appreciated. Thus, forward-looking exchange rate expectations would tend to drive any "freely" determined market interest rates in China's financial system toward zero. Then, with short-term interest rates locked at zero, the PBC would helpless to re-expand the economy. True, China's economy is now growing robustly and is not likely to face actual deflation anytime soon, but the PBC would be in poor shape to offset deflationary pressure should it occur.

China is now in a nebulous no man's land regarding its monetary and foreign exchange policies-and its experiment with inconsistent basket pegging doesn't help. Instead of clear guidelines with a well-defined monetary (exchange rate) anchor and a clear mandate to finish liberalizing its financial system, China's macroeconomic and financial decision making will be ad hoc and anybody's guess-as was, and still is, true for Japan.

附录2 主要英文参考文献译文:

实行新的汇率政策:

中国会步日本的后尘陷入流动性陷阱吗?

罗纳尔德·麦金农

斯坦福大学

20##年7月21日,中国放弃实行了10多年的固定汇率并小幅调整了人民币汇率。人民币升值前一直到目前,美国国会不断发出威胁:如果人民币不升值,就要通过一项对中国出口到美国的产品征收27.5%的进口关税的法案,并且迫使美国政府将中国仍作为“中央计划经济国家”(尽管其已具有广泛开放的特征)对待,以便对其实行其他贸易制裁——如反倾销税。

诚然,人民币汇价自7月21日调整以来,仍然在严格的控制之下,升值幅度很小——不足3%,远远低于美国批评者喋喋不休地要求的20-25%的升值幅度。

但是,这次汇价调整行动却发出了一个信号:在实现更为灵活的汇率制度的姿态下,人民币的进一步升值成为可能。

当前,可怕的是美国压人民币升值与30年前压日元升值相似。尽管也有某些差异,但有一点却是相同的;即压低利率以防范外汇风险可能使中国像日本在上个世纪90年代那样陷入零利率流动性陷阱。

一、从打压日本到打压中国

为了弄清外汇风险最有可能导致陷入零利率流动性陷阱的原因,我们首先来回顾一下上个世纪日美之间贸易方面的冲突,然后再看看近期中美之间的贸易争端。

日本对美国的贸易(主要是工业制造品)顺差从20世纪70年代开始快速增长,1986年峰值时的顺差额占美国GDP的比重达1.4%。此后,这一差额仍然非常巨大。我将这一被许多美国人和欧洲人称之为“打压日本”的紧张时期划定在1978年和1995年之间。“打压日本”意指,美国不断地以实行贸易制裁相威胁,迫使日本采取措施改善对美国有关行业的出口竞争力。要求日本同意对其钢材、汽车、电视机、机械产品以及半制成品等的出口采取严历的限制措施,辅助措施是允许日元升值。事实上,日元对美元汇率从1971年(恰在尼克松事件之前)的360:1一路升到1995年的80:1。

到了1995年,由于日元的过度升值,日本经济陷入严重的萧条,以致美国发了慈悲,美国财长罗伯特·鲁宾宣布了“强势美元”的政策。美联储与日本央行于1995年春夏数次联手干预外汇市场,以阻止日元继续走高。

此后,日元汇率大幅波动(或许波动幅度太大了),但一直未回到80:1的高点,——“日本敲打”在某种程度上停止了,然而日本至今仍未从上个世纪90年代经济遭受的巨大损失中完全恢复过来。

当前,“打压中国”取代了打压日本。中国对美贸易顺差在1986年尚微不足道,但此后顺差额的增长速度远快于同一时期日本对美国的贸易顺差,到20##年,中国对美贸易顺差已和日本对美贸易顺差持平。到20##年,前者已是后者的两倍。然而,同年,日本作为经济总量远超过中国的经济体,其经常项目(多边)顺差额达到1720亿美元,而中国只有700亿美元。但是,中国对美巨大且不断增加的双边贸易顺差集中在具有竞争性的制造业中,这就触使美国发出贸易制裁的威胁和要求人民市升值的呼声——到今年7月,中国已承受了至少4年的压力。

在上个世纪五、六十年代日本经济高速增长时期,制造业对美出口的增加速度远快于其后的10年,这与中国目前的情形非常相似。但是,日本与世界各国的对外贸易大致是平衡的(无储蓄剩余)。由于日本进口的原材料和制造品(相当一部分出自美国)增长也非常快,因而,美国能够容忍从日本进口制造品,进口竞争性行业(大多为制造业)调整的痛苦由出口的扩大所抵消。美国经常项目总体上没有逆差,所以,美国制造业收缩的压力较小。

然而,到了上个世纪七、八十年代,形势发生了巨大的变化,这一时期,美国经常项目总体上开始出现逆差(包括对日本的双边逆差),这一总体逆差主要是由巨额的财政赤字引起的国内储蓄不足所致。这即20世纪80年代著名的里根执政时期的双赤字。美国举借巨额的国际债务,主要向日本举借,最终只能转换为商品和服务的贸易逆差——且日本的主要出口产品是制造品,美国制造品的巨额贸易逆差导致本国制造业的收缩。因为美国受日本竞争而受损失的进口部门院外活动集团的政治力量日益强于日益颓缩的出口部门,打压日本的强度在上个世纪80年代更为加大了,直至1995年才减弱。

新世纪伊始,当中国作为主要贸易国出现在世界舞台上时,正赶上美国由于新一轮战争支出巨大而陷入财政赤字,同时美国家庭储蓄率处于出人意料的低水平,——这或许与美国房地产泡沫有关。低储蓄率导致巨额的经常项目逆差,20##年逆差额占GDP的比重达到6%,——远远大于日本和中国经常项目顺差之和。

比较而言,日本和德国的制造品出口以及经常项目顺差总量远超过中国,但为何对中国的打压要比对日德的打压更为强烈呢?这是因为世界贸易,特别是亚洲贸易运作组织是非常特殊的。中国对美贸易的双边顺差较大,也更容易引起美国政治家们的关注,实际上,当前所有亚洲国家的经常项目都是顺差,有几个国家还对中国有双边顺差。中国从日本、韩国、台湾地区、新加坡以及欧洲国家 (如德国)购买高科技的资本货物和工业中间产品,也从亚洲及拉美等世界各国购买原材料,用于生产各种各样的技术含量居中的消费品出口到美国市场。中国的许多出口产品为最终产品,但在中国本土增加的附加值并不高,这是因为用于生产出口产品的原料和中间产品进口自亚洲和世界各国。

然而,美国人只看到大量涌入美国的中国产品的“中国制造”这一标签的一个侧面,美国的政治家们则缺乏远见地把中国谴责为不公平的竞争者。但中国仅仅是整个亚洲对美出口扩张这一冰山之一角,尽管这一巨大冰山的真面目尚未完全显现。而亚洲对美出口的扩张恰恰反映了亚洲各国的储蓄率非常高,而美国的储蓄率则畸形地低。

二、有选择地限制出口

当前,打压中国主要表现为迫使人民币升值,或者迫使中国允许人民币对美元汇率更加“灵活”。如果人民币汇率实行浮动,那么,中国通过贸易顺差和外国直接投资的流入积累起来的美元资产,会导致人民币汇价不断加剧地无限期走高。

1978——1995年打压日本时期,美国要求日元升值,同时要求日本“自愿”地对某些特种产品的出口实行限制。因为当时日本大量涌向世界和美国市场的出口产品集中于重工业——如钢材、汽车、电视机和半成品等,这就使得美国通过限制日本某些特种产品出口的增长来减弱对美国相关进口竞争性行业的影响具有实际意义。而美国重工业中的院外活动集团比较集中且政治势力较强。

相比而言,近期中国对美出口的产品多为中低技术含量的轻工业产品,而不是集中于特定的重工业领域,行业非常分散,因而美国特种行业持贸易保护主义态度的院外活动集团对中国的态度不像上个世纪对日本那样强硬。中国对美出口比较集中的行业是纺织品和服装。20##年1月1日,原来一直限制中国纺织品出口的国际多边纤维协议(MFA)终止,这使中国在纺织品和服装行业的地位更加复杂化了。

然而,在实际政策层面,为了避免国外制造麻烦,中国可参照日本过去的做法自愿地,但只是暂时地再通过关税和配额的方式对其纺织品的出口进行限制,尽管这不是法定必须做的。

三、汇率和贸易平衡

对某些产品的出口实行暂时的限制——这些产品出口的增加会扰乱进口国的市场——也是非常好的方法,美国要求中国货币对美元升值,如同过去要求日元升值一样,是缺乏根据的。一个债权国的货币对世界主导货币持久升值是一剂会使经济增长放慢,最终导致通缩的药方。日本对其上个世纪90年代由日元升值遭受的损失非常懊悔。而日元升值对其贸易顺差的影响并不明显。

然而,近期太平洋两岸颇具影响力的经济学家们在金融媒体上连篇累牍地撰写文章,纷纷建言,为了矫正美国经常项目的逆差,美元必须大幅度贬值。为此,他们极力主张东亚国家应放弃钉住美元的汇率政策。特别是中国应将其人民币大幅度地升值,然后转入无管制的浮动汇率制。

上述主流观点建立在如下两个假定前提上。其一,任何一个亚洲国家的货币对美元升值,就会减少其对美国的贸易顺差;其二,为了建立起公平的国际竞争环境,就必须实行更加灵活的汇率制度。但是,在以美元为国际本位货币的制度中,这两个假定在经验上都不成立。下面,我们首先来探讨汇率对贸易平衡的影响。

如果对汇率进行间断性的调升,那么,这种升值预期反映为对未来相关的货币政策的预期:升值国家的货币政策紧缩并产生通缩,而贬值国家的货币政策相对较松,通胀上升。升值的债权国通过三个渠道产生通缩效应:

其一,是国际商品套利效应。升值会直接降低进口商品的本币价格,而进口商品在世界市场上的美元价格则相对稳定,处于美元本位制边缘的国家,其汇率变动的传递效应远大于美国本国。因为国内出口商品的外汇价格更高了,外国对这些商品需求的下降直接降低这些商品的本币价格。国外需求的下降也会间接地降低这些商品的国内需求。

其二,负的投资效应。一国货币升值后,就会使该国成为更昂贵的投资地,特别是在出口和进口竞争部门的投资活动。对外国直接投资和本国出口企业更是如此。即便是外国在该国投资生产的非外贸商品和劳务也会受到抑制,因为绝大多数外国潜在的投资者是资本约束型的。也就是说,这些投资者受到其所持股份和净值的制约,货币升值使得投资者购买一定数量的物质资本需投入更多的美元。其结果是,对升值国的投资下降。

其三,负的财富效应。持有美元资产的国际债权人会受到财富负效应的影响,因为以本币计算的美元资产贬值了,货币升值的通缩影响强化了。这种负财富效应会进一步降低国内消费和投资,从而加速国内经济的下降(经济增速降低)。

以上,我们讨论了货币升值影响国内支出并引起通缩进而影响持有美元资产债权人的三个渠道。国内总需求的下降也会导致对进口产品需求的降低,抵消进口产品价格下降的作用。事实上,货币升值的相对价格效应会使外国人购买本国出口产品的价格更昂贵,因而出口会下降,但是进口的下降也会相当严重,以致从理论上减弱了对贸易差额的影响。例如,20世纪80年代中到90年代中期日本被诱使(被迫)对日元屡次升值,其结果是日本经济陷入长达10年的通缩和萧条,而相对于GDP的贸易顺差并没有明显的降低。

四、作为货币锚的汇率

除了旨在“调整”贸易差额外,许多经济学家和金融媒体的评论员——包括国际货币基金组织这样的重量级机构的专家们——也极力主张实行灵活的汇率制度,以使国内宏观经济政策能够阻断经济衰退和国际收支变动的联系。国际货币基金组织建议中国实施更为灵活的汇率制度,以增强其货币政策的独立性,特别是独立于美国的货币政策。我们不禁要问,这一建议对经济增长迅速而金融体系尚不完善的发展中国家适用吗?

除了在欧洲,美元是国际商品和劳务贸易的主要计账货币。所有的主要产品,工业原材料、石油、粮食等的对外贸易均使用美元开立发票,有一些发达国家出口制成品和劳务以本币开票。但既使在这些国家,也将美元价格作为参考价。所以,如果可能的话,全世界的制造商都会以美元定价。因为绝大多数国家在对外贸易中都以美元计价,因而,从总体来看,这些国家是一个自然的美元区。日本是亚洲唯一在一些对外贸易中使用本币计价的国家。但日本也有将近一半的出口和3/4的进口以美元计价。而无论是中韩贸易或是泰(国)马(来西亚)贸易,均使用美元计价。

正是因为上述三个方面密切联系在一起的原因,每一个东亚国家都尽力将其货币正式或非正式地钉住美元,因而,也就将其货币政策和中心国家牵连在了一起。

首先,只要美元在一个可贸易商品和劳务宽泛的篮子中的购买力是稳定的,像上个世纪90年代中期到目前那样,那么,钉住美元也就对国内价格水平起到了锚的作用。东亚各国之间以美元计价的贸易要比与美国的贸易范围大得多。由于各个东亚贸易伙伴国的货币也都钉住美元,因而,每一个国家钉住美元的锚效应就会更强一些。

其次,东亚国家在彼此的市场上及在欧美市场上的竞争力都很强,特别是在制造业方面。没有那一个东亚国家愿意其货币对世界主导货币骤然升值。因为升值会导致其在出口市场上的商业竞争力受损,进而导致经济增长的总体下降。如果持续升值,就会导致全面的通缩。

再次,目前的中国与上个世纪五、六十年代的日本一样,经济快速发展,而国内金融市场处在转轨时期,未完全实现自由化。在中国以银行为基础的不太成熟的资本市场中,货币供应高增长且不可预测,而利率基本上仍由官方确定。在这种情况下,中国人民银行不能依据国内货币供应量的增长或利率的高低作为判断货币政策松紧的指标。因而,就需要依赖一个外部的货币锚——对上个世纪五、六十年代的日本来说360日元兑1美元,对1995年到20##年的7月21日的中国来说8.28人民币兑1美元——作为本国货币当局参照的基准。为了确保汇率目标的实现,政府可在特定的范围内,以行政手段控制银行信贷、存款准备金、利率的调整、针对不断累积的官方外汇储备对货币供应的影响进行对冲操作。这种辅助的,间接的方式被用来稳定国内物价。

然而,这种外部的货币基准在中国向市场经济转化的最初阶段是没有用处的。从1978年开始,中国逐步取消国内物价管制,但除了几个经济特区外,对外贸商品的价格体制未作改革,在此后的差不多15年的时间内,中国总体上看未开放国际商品和金融的套利领域。外贸由国有外贸公司经营,试图以此来切断国内外价格和汇率的联系,——这即所谓的气阀制度。1978年,人民币对美元汇价为1:1.7。那时,人民币是高估了,但这一汇率水平没有实际意义。上个世纪80年代,人民币数次贬值,1992年贬到1:5.5时对国内价格没有大的影响。进入上个世纪90年代初,中国执行实际上独立于外汇的货币政策,在这种情况下,要独立地稳定其国内价格水平是很困难的。

到了1994年,中国统一了外汇体制,开始实行经常项目下的可自由兑换,这使得外贸商品和劳务可以直接在市场上进行套利。这一改革是没错的。但是在将官方汇率和所谓的外汇调剂市场汇率统一的同时,人民银行将人民币的官方汇价贬值的幅度太大了,从1:5.6贬到1:8.7(1:8.7是调整前的市场汇价)。这一大幅度的贬值导致了1993~1996年严重的通货膨胀,1995年CPI达到20%,这是对一个更为开放的经济体汇率贬值幅度太大的惩罚性结果。

然而,从1995年到20##年7月21日,中国一直将汇率维持在1美元兑8.28元人民币(上下0.3%的浮动)的水平上,在这10年当中,货币政策和财政政策都服从于维持这一固定汇率——包括1997-1998年人民币顶住了巨大的压力没有贬值。为了履行WTO的义务,中国进一步降低了进口关税和限额。从20##年7月到20##年7月中国的CPI仅上涨了1.8%,(20##年,包括石油的初级产品价格上涨没有传递到零售商品的价格上)较之上个世纪90年代,中国在新世纪成功地运用国际货币锚稳定了国内价格水平。

在中国通胀率与美国趋同的背景下,中国的货币工资增长率很高。处于“赶超”(Catchup)阶段。中国人均产量水平远远低于发达工业国家,因而人均生产率的增长速度自然很高。然而,只要货币工资的增长反映了生产率(目前是每年10~12%)的提高,中国就能够维持其国际竞争力,过去10年中国发生的情况和1950-1970年日本在固定汇率时期发生的情况就是如此。只要确保名义汇率维持不变,那么,边缘国家的工资增长就会自然地与开放的贸易部门的生产率增长相适应。例如,中国的制造业和上个世纪五六十年代的日本。

只要货币工资的高增长与生产率的提高程度相适应,就能够确保边缘国家的通胀率和中心国家趋同,同时也能确保固定汇率的可维持性。但是一旦货币升值,那么进一步的升值的可能性就更大了。外贸部门的雇主在确定工人的工资时,就会更加慎重,于是,货币工资的增长就会低于生产率的增长,由预期的货币升值导致工资增长放慢最终会形成普遍的通缩压力。

五、中国会陷入流动性陷阱吗?

部分由于为了确保符合加入WTO的条件,金融自由化仍是中国政府的一个重要目标。“自由化”既是一个国内范畴,也是一个对外范畴,政府要逐步放宽利率管制,特别是放宽对银行存货款利率的管制。随着利率的自由化,要大力发展国内不同期限的债券市场。最终要实现国际收支中资本项目的开放,从而能够建立起用了规避外汇风险的更加活跃的期货市场。

从长远看,以上几点是中国改善资本市场效率重要的而且正确的目标。然而,当前中国经济在人民币升值的威胁下,金融体系的自由化可能会产生负面的短期后果。面对没有消除的外汇风险,即人民币升值的可能性,接近于零利率的流动性陷阱可能出现——甚至很难避免。20##年中,中国银行拆借利率(CHIBOR)已接近于1%,而同期美国联邦基金利率已升到3%。尽管银行的存款利率和一些贷款利率仍由人民银行决定,但中国银行间的拆借利率已基本自由决定,(从1996年开始,日本的短期利率接近零:可怕的流动性陷阱)。这里,有一个很重要的问题,这就是保持美元资产和人民币资产组合的平衡。在开放的资本市场,由于承担人民币可能贬值的风险,因而美元资产持有者必然要得到高利率的补偿,但是美元资产的利率是由独立于中国之外的世界市场决定的。在这种情况下,保持美元和人民币适当利差的唯一方法是将人民币资产的利率降到美元资产的利率以下。

如果人民币资产的利率不及时下降,那么短期资本(“热”钱)就会流入中国。因为投资者会千方百计地将手中的美元兑换成人民币,由此产生的人民币升值压力迫使人民银行进入外汇市场买入美元,以缓减进一步的升值压力。与此同时,中国巨额的美元外汇储备,目前已近8000亿美元,会导致国内基础货币的膨胀,进而推低短期利率,最终逼近零。

需要指出的是,人民币仅向上浮动,或者分步升值,并不能解决上述难题,只能使问题更加严重。升值导致通缩,进而推低国内利率,从上个世纪日本的经验来看,日元反复升值,利率逼近于零,于是通缩发生。既然人民币事实上的升值未必能降低中国的贸易顺差,那么,美国就会继续压人民币升值——正像1995年以前对日本所做的那样。最好的办法是,中国实行可信的固定汇率,使人们不再担心人民币会升值。在市场利率保持在正常水平——如接近世界或美国的利率水平的情况下,可以推进金融自由化。然而,最近中国放弃了维持10年对美元1:8.28的:“传统汇价”,使得保持公信的固定汇率策略更加困难了——在一定时期内也成为不可能的事了。

那么,次优的办法是,中国继续甚至加强对流动性金融资产流入的限制——以此减弱来自外部推低利率的压力。与此同时,人民银行有必要继续将银行存贷款利率定在相对自由的银行间拆借利率之上。只有贷款利率高于零,银行才能有利差收入。

从上个世纪90年代初到现在这段漫长的时期,日本的利率一直接近于零,这使得商业银行的名义利润大幅度降低。在这种情况下,商业银行不可能解决不良贷款问题,也不愿意扩大信贷——这就使20世纪90年代日本的经济衰退更加严重了。

六、结论

20##年7月21日人民币汇率调整后,如果中国要避免像日本那样陷入流动性陷阱,就必然会放慢金融市场开放的进度,这是中国在推进市场经济建设的宏伟进程中的一个弯路。如果中国像之前的日本那样陷入零利率的流动性陷阱,那么,人民银行和日本银行一样,很难消除经济中的通缩压力,大幅度的汇率升值就会发生。不断地进一步升值的威胁——因为贸易顺差没有减少(这与流行的观点相反)——以及接近于零的短期利率不利于商业银行刺激经济复苏。诚然,当前中国经济增长强劲,近期内不太可能发生实际的通缩。但一旦发生通缩,人民银行就会难以应对。

当前,中国在货币政策和汇率政策方面迷雾重重。如果没有一个在明确的方针指导下选定的货币(外汇)锚,没有责任明确的部门负责金融体系的开放,那么,中国的宏观经济和金融决策将会显得与众不同,也会成为任人猜测的对像——日本的过去和现在就是例子。

致谢

[1] 杨胜刚、姚小义主编《国际金融》,湖南大学出版社20##年版

[d1]1.2.1以下的标题用⑴,⑵等。