搭讪心理学:如何去正确的搭讪

搭讪是一门学问。外向女喜欢幽默男,精神质女喜欢坏男人。而女性搭讪男性的套路中,最受男性追捧的是——性!看来出手之前,你需要先做好功课了。

约会时,男人通常被描绘成略占优势并充满诡计的。但其实他们普遍不大擅长搭讪。比如,搭讪时男人常拙于言辞、信口辞“黄”(荤段子),然而荤段子其实是最没可能让交谈继续下去的搭讪方式。这就带来了一个问题:那为什么男人还一直用它?

搭讪是一种选择工具

英国中央蓝开夏大学(University of Central Lancashire)心理学系的贝欧(Chris Bale)和爱丁堡大学(University of Edinburgh)心理学系的库柏(Matthew Cooper)对此做出了简洁明了的回答:搭讪套路可能是一个男性选择特定女性的方式。换句话说,男性之所以爱用荤段子,是因为他们想以此来寻找特定类型的女性(那些比较开放,不那么挑剔,容易得手的……)。同样的,男性也会用描述性格特征或者本土化的开场白来显示他们是个很好的长期伴侣。

随后,库柏和他的团队做了进一步试验,试图阐明个性与搭讪的关系。在库柏的研究中,被试(均为女性)需要评估40个男士向女士搭讪的场景,在每个场景中,男士都会使用不同类型的方式来搭讪。然后,被试们需要根据开场白来推断这场对话会如何发展,这段关系是否能够继续。

通过对这些套路进行分析,研究者们整理出了其中最重要的4个因素,分别是:

好伴侣因素 ——具备这类因素的搭讪通常会提到文化、性格或财富。比如,你知道我在XXX博物馆看到的那件神奇的东西吗?

恭维因素 ——比如,哦,你长得好像XXX(某明星或某美女)啊。(女性通常觉得这个开场白好冷。)

性暗示因素 ——比如提到床或者滚床单什么的。(女人通常不喜欢这个开头。) 幽默因素 ——比如,我能给你买座小岛吗?(女人很喜欢被有幽默感的男人搭讪。) 4种男人

在库柏的研究中,被试还进行了“约会伴侣偏好性测试”(Dating Partner Preference test),统计结果女性常常将男人归为4类。

居家男人 ——他乐于助人、体贴、会欣赏你,像只狗狗般讨人喜欢。这类男人的评价通常也被女性认为与好伴侣因素相关。

提供者 ——他进入丛林,杀猪、生火、盖小木屋、满足温饱。这类男人的分类与恭维因素相关。

领袖 ——他健谈、自信、意志坚强,是你百依百顺的对象。这类男人的分类与恭维和性暗示因素相关。

坏伴侣 ——善变、自负、依赖、认为一切都是你的错。但是……男人不坏,女人不爱。这类男人的分类主要与性暗示因素相关。

此外,被试们还需要填写一张个性评价表,来评价她们自身的精神质(不恰当情绪反应和暴力倾向)、外向性(活泼,合群,外向型)和神经质(链接内容),在进行了这些分类以后,就可以寻找个性和搭讪方式之间的联系了。

根据个性选择搭讪方式

通过分析女性被试的个性,及其对搭讪因素和男人类型的评价,研究者们发现,的确不同个性的女士偏好不同因素的搭讪。外向性特质高的女性,更重视幽默因素,也更喜欢领导者型的男子。而精神质的女子则对坏伴侣情有独钟,神经质型的女子则爱好居家男人。

这就意味着,男人选择的不同类型的搭讪套路会对女子的回应有一定的影响,而通过女性对特定类型搭讪的回答,男人能够有效地判断女性的个性。比如男人对那些想找个“坏伴侣”的女人搭讪时就可能使用荤段子或者恭维,而那些想找个外向性女人的男性则可以用笑话开场。

需要注意的是,个性特征和搭讪套路之间的相关性并不是很强(在0.2-0.4之间)。因此,个性特征并不能主导对搭讪的反应。不过,既然搭讪和个性是有关系的,为了脱光,何不在这方面下点功夫呢?

当然,除了上述几种搭讪套路,还有一些搭讪方式是女性普遍都很喜欢的,了解这些会让男人事半功倍。它们包括体现出对女性的帮助意愿的,愿意让女性占据控制权的,以及那些以并不露骨的方式展现财富的搭讪方式。

男性对女性搭讪套路的看法

前边说的都是男性搭讪套路,与之相对,研究者们也考虑了女性的搭讪套路。在女性搭讪男性的套路中,最受男性追捧的是——性!也就是说,男性最喜欢女人带有性暗示的搭讪。而男性不太喜欢的女性搭讪方式是幽默——这跟女性对男性搭讪方式的喜好正相反。

第二篇:如何正确的安慰人_来自心理学的证据

JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology2007,Vol.92,No.3,458–475Copyright2007bytheAmericanPsychologicalAssociation0022-3514/07/$12.00DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458

EffectsofSocialSupportVisibilityonAdjustmenttoStress:

ExperimentalEvidence

ColumbiaUniversity

NiallBolger

NewYorkUniversity

DavidAmarel

Previousfieldworkhassuggestedthatvisiblesocialsupportcanentailanemotionalcostandthatasupportiveactismosteffectivewhenitisaccomplishedeither(a)outsideofrecipients’awarenessor(b)withintheirawarenessbutwithsufficientsubtletythattheydonotinterpretitassupport.Toinvestigatethelatterphenomenon,theauthorsconducted3experimentsinwhichfemaleparticipantswereledtoexpectastressfulspeechtaskandaconfederatepeerprovidedsupportinsuchawaythatitwaseithervisibleorinvisible(N?257).Invisiblesupport(practicalandemotional)reducedemotionalreactivityrelativetovisibleandnosupport.Visiblesupportwaseitherineffectiveoritexacerbatedreactivity.Explanatoryanalysesindicatedthatsupportwaseffectivewhenitavoidedcommunicatingasenseofinefficacytorecipients.

Keywords:relationships,socialsupport,mentalhealth,stressandcoping,processanalysis

Althoughtheneedforsocialrelationshipsisconsideredfunda-mentaltohumanpsychology(Baumeister&Leary,1995;Reis,Collins,&Berscheid,2000)andthepresenceandqualityoftheserelationshipsisessentialtophysicalandpsychologicalwell-being(Berkman,1995;Berkman,Glass,Brissette,&Seeman,2000;S.Cohen,1992;Stroebe&Stroebe,1996;Uchino,Cacioppo,&Kiecolt-Glaser,1996),oneofthemorepersistentpuzzleshasbeenhowtoexplainthesebeneficialeffects.Ontheonehand,thereisampleevidencethatpeoplewithlargersocialnetworksandthosewhoperceivethatsupportisavailabletothemshowlessreactivitytostressorsorhavebetterhealth(S.Cohen&Wills,1985;House,Landis,&Umberson,1988;House,Umberson,&Landis,1988).Ontheotherhand,studiesinvestigatingwhetherconcreteactsofsupportexplainthesebeneficialeffectshaveproduceddisappoint-ingresults(Barrera,1986;Bolger,Zuckerman,&Kessler,2000;Coyne&Bolger,1990).Althoughthereareexceptions(e.g.,Abraido-Lanza,2004;N.L.Collins,Dunkel-Schetter,Lobel,&Scrimshaw,1993;Feldman,Downey,&Schaffer-Neitz,1999),moststudieshavefoundnulloradverserelationsbetweenthereceiptofsupportandadjustment.

Variousmechanismscouldexplainthisdiscrepancyinfindings,suchasmiscarriedhelping(Coyne,Wortman,&Lehman,1988;Martire,Stephens,Druley,&Wojno,2002;Newsom&Schulz,1998);feelingsofindebtednessorinequityfollowingsupportreceipt(Gleason,Iida,Bolger,&Shrout,2003);reversecausation,thatis,pooreradjustmentleadingtoincreasedsupportreceipt(Seidman,Shrout,&Bolger,2006);orunmeasuredstressorsever-

ityactingasathirdvariable,thatis,stressorseverityleadingtobothpooreradjustmentandincreasedsupportreceipt(Barrera,1986;Bolger&Eckenrode,1991;Seidmanetal.,2006).Giventhelikelycomplexityandvarietyofsupportiveinteractions,itisunlikelythatanysinglemechanismwillprovideasufficientac-count.Evidenceforaparticularmechanism,however,wasfoundinadailydiarystudyofdyadsunderstress(Bolgeretal.,2000),namely,thatsupportattemptsbyprovidersthatwereunacknowl-edgedbyrecipientswerethemosteffectiveinreducingdistress(seealsoShrout,Herman,&Bolger,2006,forabroadersetofanalysesofthesamedataset).Bolgeretal.(2000)interpretedtheseresultsasshowingthatsupportattemptscanbebeneficial,thatawarenessofthemcanentailanemotionalcost,andthatatleastsomeformsofskillfulsupportareaccomplishedinawaythatisnotnoticedorinterpretedassupportbyrecipients.

AlthoughthediarystudyevidencebolsteredthenotionthatwhatBolgeretal.(2000)calledinvisiblesupportwassuperiortovisiblesupport,theresultsofthisnonexperimentalfieldstudywerenotimmunetorivalinterpretations.Thecurrentarticlereportsonthenextstepinthisprogramofresearch,inwhichwesoughttorefineourthinkingabouttheinvisiblesupportphenomenonandtobringit,ifpossible,underexperimentalcontrolinalaboratorysetting.Wealsosoughttousethegreatercontrolaffordedbyalaboratorysettingtoisolatefactorsthatmightmediatetheeffect.

Perceived,Received,andInvisibleSupport

Giventheconsistentevidencethatsocialsupportavailabilityprotectspeoplefromtheeffectsofstressors(S.Cohen,1992;S.Cohen&Wills,1985;Hobfoll&Vaux,1993;Stroebe&Stroebe,1996;Wills,1991),itmightseemreasonabletosupposethatpeoplewhoareintegratedintosocialnetworksorwhoperceivethatsupportisavailabletothemmakeeffectiveuseofthissupportintimesofstress.Researchoverthepast2decades,however,hasnotonlyfailedtoshowthatsuchpeoplemobilizesupportunderstress(Dunkel-Schetter&Bennett,1990;Lakey&Drew,1997;Wethington&Kessler,1986)buthasfailedaswelltoshowthatreceivedsupportisconsistentlybeneficialinsuchsituations(Bar-458

NiallBolger,DepartmentofPsychology,ColumbiaUniversity;DavidAmarel,DepartmentofPsychology,NewYorkUniversity.

ThisresearchwassupportedinpartbyNationalInstituteofMentalHealthGrantMH60366.ThedatawerecollectedbyDavidAmarelinpartialfulfillmentofmaster’sanddoctoraldegreerequirementsfortheGraduateSchoolofArtsandScience,NewYorkUniversity.

CorrespondenceconcerningthisarticleshouldbeaddressedtoNiallBolger,DepartmentofPsychology,ColumbiaUniversity,406Schermer-hornHall,NewYork,NY10027.E-mail:bolger@psych.columbia.edu

EFFECTSOFSUPPORTVISIBILITY

459

rera,1986;Bolgeretal.,2000;Coyne&Bolger,1990).Forexample,Helgeson(1993)foundthatperceivedavailablesupporthadabeneficialeffectonadjustmenttoheartattacks,whereasreceivedsupportfromsignificantothersappearedtohaveaharm-fuleffect.Frazier,Tix,andBarnett(2003),intworecentstudiesofkidneytransplantpatients,foundnolinkbetweensupportivebe-haviorsbysignificantothersandpatientdistress.

Thereareanumberofplausiblereasonswhyreceivedsupportmaybedetrimentaloratleastineffectiveinsomesituations.First,researchersonhealth-relatedcaregivinghavefoundthatasubstan-tialproportionofrecipientsreceivingcarefromspousescomplainoffeelingoverlydependentonandindebtedtothespouse(New-som,1999).Second,researchershaveshownthatinequitiesinreceivedsupport,namely,feelingoverbenefited,canleadtoin-creaseddistress(e.g.,Gleasonetal.,2003).Third,experimentalworkhasshownthatreceivinghelpcanhavedetrimentalemo-tionaleffects.Inreviewingthisliterature,Fisher,Nadler,andWhitcher-Alagna(1982)proposedthatthreatstoself-esteembestexplainthecostsofbeinghelped(seealsoNadler&Fisher,1986).Eventhoughthisexperimentalworkismostlyontheeffectofshort-termhelpfromstrangersandmaynotnecessarilygeneralizetoreal-worldcontextsofsupportincloserelationships(seeWills,1991,foradiscussionofthisissue),atleastonestudyhasshownself-evaluationcostsofreceivingaidonego-relevanttasksfromclosefriends(Nadler,Fisher,&BenItzhak,1983).

Howeverreceivedsupportoperates,itsdistinctivenessfromtraditionalmeasuresofperceivedavailablesupportisnotindoubt.Ifperceivedsupportisnotfosteredbyreceivingsupport,thenhowdoesitcomeabout?Someresearchersarguethatperceivedsupportisbestunderstoodasanindividualdifferencevariable(seePierce,Lakey,Sarason,Sarason,&Joseph,1997,forareview).Inthisview,thefeelingofbeingsupportedreflectsworkingmodelsofinteractionbasedonearlyexperienceswithsignificantothers(e.g.,Bowlby,1969).

Othershavearguedthatperceivedsupportisrootedintheeverydayfabricofrelationships,intheroutineinteractionsthatpeoplehavewiththeirfriendsandpartners,interactionsthatarenotnecessarilyviewedasactsofsupport(Leatham&Duck,1990;Rook,1987;Thoits,1985).Lieberman(1986),inreviewingthefindingthatmanypeopleinsupportivenetworksclaimnottoturntothesenetworksforhelp,hasarguedthatsuchpeopleprobablydoreceivesupportbutthatitisdeliveredsosmoothlythattheydonotnoticeit.Indeed,CoyneandBolger(1990)positedthatitistheabsenceofexplicitsupportthatmayattesttothestrengthofacloserelationship.Explicitor“visible”actsofsupportfromaclosepartnermayrepresentreparativework,potentiallysignalingprob-

lemsintherelationship.Thus,onepossibleexplanationforthediscrepancybetweentheeffectsofperceivedandreceivedsupportisthatthemosteffectivesupportfromfriendsandpartnerstakesplace“betweenthelines”andeithergoesunnoticedorisnotinterpretedassupport.Thisiswhatwerefertoas“invisiblesupport”(Bolgeretal.,2000).

WhenSupportVisibilityMattersinDyadicInteraction

Supportiveactscanbedistinguishedintermsoftheirlocationinastressandsupportprocess.Inthecaseofdyads,Figure1showsaprogressionofstagesthatbeginswithafocalpersonexperienc-ingademandingeventoractivityandendswithherorhimaskingforhelpfromadyadpartner.Highlightedbynumberedarrowsarepotentialpointsofsupportprovisionbythepartner,supportthatifsuccessfulcanpreventaprogressiontothenextstageintheprocess.Althoughnecessarilysimplified,Figure1allowsustomakesomeusefuldistinctions.

ThemajordistinctionshowninFigure1isbetweenwhatwetermanterogatorypointsofsupportprovision(1–4),thosethatoccurbeforethefocalpersonhasreachedastageofaskingforsupport,andpostrogatorypoints(5),thosethatoccurfollowingarequestforsupport.Althoughthereareexceptions,ourviewisthatinvisiblesupportismostlikelytooccurandfunctionsbestintheanterogatorystages.Visiblesupport,bycontrast,ismorelikelytobeanetbenefitinpostrogatorystages,butdependingonthestressorandrelationshipcontext,itmayalsobebeneficialatearlierstages.

Thefirstpointofsupportprovisioniswherethedyadpartnerpreventstheoccurrenceofademandingevent.Ifthisisaccom-plishedoutsideoftherecipient’sawareness,noappraisalsofstressfulness,ofpersonalcompetence,ofsupportneeds,orofcopingeffortwillberequiredoftherecipient.Thus,spouseswithamajorillnessmaybeshieldedfromexposuretohouseholdandchildcarestressorsbythebehind-the-sceneseffortsoftheirpart-ners.

Asecondpointofsupportprovisionisoneinwhichademand-ingeventoractivityoccursbutthepresenceoractionsofthedyadpartnerpreventrecipientsfromappraisingitasstressful.Forexample,ifonespousereceiveswordofanupcomingjobinter-view,thepartner’sdeliberateadoptionofacalmpositivemannercanresultinthespouseappraisingtheinterviewasanopportunityratherthanathreat.

Athirdpointofsupportprovision,andtheoneweexamineempiricallyinthisarticle,isoneinwhichanalreadystressedpersonreceiveshelpwithouthavingtoexplicitlyaskforit.

Such

Figure1.Hypotheticalstressandsupportprocessforadyadmember,showingalternativepointsofsupportprovisionbythedyadpartner

460

BOLGERANDAMAREL

actsareinvisibletotherecipientwhentheyareenactedinasufficientlysubtleorindirectwaythattherecipientdoesnotinterpretthemassupport.Anexamplemightbesupportthatisdeliveredundertheguiseofseekingratherthanofferinginforma-tion,asinthecaseofanemployeewhoaidsastrugglingcoworkerbyseekinghelpfromasupervisoronasharedtask.Anotherexamplemightbeoneinwhichapeerstrategicallyevokesdistress-reducingsocialcomparisonsinastudentworriedaboutanupcomingexaminationbydrawingattentiontoherownlackofpreparation.Wesuspectthatskillful,indirectmethodssuchasthesearecommonwaysthatinvisiblesupportisenacted,particu-larlywhenpotentialsupportersarepeers.Bycontrast,visiblesupportgivenatthispointinastressprocessinvolvestheriskofinvokingorincreasingrecipients’senseofincompetenceand,inpeerdyads,recipients’tendencytoseethemselvesaslesscompe-tentthanthesupportprovider(i.e.,tomakeupwardsocialcom-parisonsoncompetence).

Afourthpointofsupportprovisionisoneinwhichthestressedpersonhasmadethejudgmentthatheorsheisnotabletocopewiththestressorbuthasnotyetovercomeanyconcernsaboutautonomyorappearingincompetenttodecidetoaskforhelp.Herewebelievethatforskillfulsupportprovidersthebalanceisstillinfavorofprovidinginvisiblesupport,butdependingonthetypeofdyadicrelationship(e.g.,peervs.intimatepartner),theidentityrelevanceofthestressor,andthecompetenceofthepartnerinthestressordomain,visiblesupportmaybemoreappropriate.Ofcourse,ifsuchsupportisgiveninaheavy-handedway,itmayreinforcefeelingsofinefficacyandinpeerdyadsincreaseupwardsocialcomparison.

Thefinalpointofsupportprovisionisoneinwhichapartnerexplicitlyasksforhelp.Visiblesupportgivenatthispointtypifiesthecanonicalsupporttransaction,andassumingthesupportmatchestheneedsoftherecipient(Cutrona&Cole,2000;Cutrona&Russell,1990),itcanhelphimorhertoreappraisethesituationaslessthreateningortocopeeffectivelywithit.

AnExperimentalParadigmforStudyingSupport

VisibilityEffectsinPeerDyads

TheBolgeretal.(2000)articlewasunabletoempiricallydistinguishwheninadailystressprocessinvisiblesupportoc-curred,butthepresumptionwasthatitoccurredattheanterogatorystage,thatis,atPoints1–4inFigure1.Asnotedabove,ourfocusinthisarticleisonsupportvisibilityatPoint3intheprocess,whereparticipantsalreadyappraiseasituationasstressfulbuthavenotreachedasufficientlynegativeviewoftheircompetencythattheydecidetoaskforhelp.

Centralgoalsofthecurrentresearch,therefore,weretoimproveontheBolgeretal.(2000)study(a)bybeingexplicitaboutthecontentandtimingofthesupportiveactsand(b)throughexperi-mentalcontroltorendertheseactsuncorrelatedwiththerecipi-ent’sdistressandotherpotentialthirdvariables.Also,(c)thisresearchsoughttoexaminemechanismsthatcouldexplainwhyinvisiblesupportwasmoreeffectivethanvisiblesupport.Wasinvisiblesupportmoreeffectivebecauserecipientswerelessawareoftheirowndifficultiesanddistress,hadagreatersenseofefficacyorareducedsenseofindebtedness?

Toaccomplishthesegoals,wedevelopedalaboratory-basedstressorandsupportparadigmtobeusedwithundergraduate

participants.Thestressorinvolvedexposingparticipantstoade-mandingachievement-relatedsituation,oneinwhichtheyex-pectedtogiveaspeechonatopicpersonallyimportanttothemandtobeevaluatedbyanaudienceofgraduatestudents.Supportvisibilitywasmanipulatedbyusingaconfederateposingasastudentpeerwhoprovidedhelptotheparticipantinoneofseveralcarefullyscriptedways.Thekeyexperimentaloutcomewaspar-ticipants’emotionalreactivitytothestressor,whichwasassessedbytheriseintheirpsychologicaldistressbecauseoftheanticipatedspeech.

Therearemajordifferencesbetweenthecurrentexperimentalapproachandthenonexperimentalfieldstudyapproachinwhichtheinvisiblesupportphenomenonwasoriginallydemonstrated.Nevertheless,essentialelementsoftheinvisiblesupportphenom-enonarepreserved,namely,adyadiccontextinwhichafocalperson’scompetenceinavalueddomainischallengedandadyadpartnerenactssupportinwaysthatvaryintheirvisibilitytothefocalperson.Fromatheoreticalpointofview,themostimportantdifferencebetweenthetwoapproachesisthatthecurrentapproachfocusesonsupportfromanunfamiliarpeerratherthanfromanintimatepartner.People’snormativeexpectationsarethattheycanrelyonintimatepartnersforsupportbutcannotrelyuponitfromunfamiliarpeers.Wetookpains,therefore,tocreateasituationinwhichtheprovisionofsupportbyanunfamiliarpeerwasareasonableevent.Alsooftheoreticalsignificanceisthelikelyroleofsocialcomparisonprocesseswhensupportisbeingofferedbyapeer,someonewhoismorelikelythananintimatepartnertohavecompetenciesthataresimilartothepersonunderstress.

Wechosetoimplementthestressorusingananticipatedspeechparadigmbecausethisparadigmisknowntobeaneffectivelaboratorystressoramongundergraduatesandcanbeextendedtoincorporatesupportprovisionbyaconfederatepeer(Pierce,Sara-son,&Sarason,1992;Uchino&Garvey,1997;Winstead,Der-lega,Lewis,Sanchez-Hucles,&Clarke,1992).Participants’in-vestmentinthespeechtaskwasincreasedbyhavingthemspeakonatopicthattheyhadpreselectedaspersonallyimportant.Furthermore,weusedacoverstorythatwaslikelytobebothstressfulandmeaningfultocollegestudents:gradingoftheirperformanceinavalueddomain.

Thespecificcontextinwhichtheconfederatepeerprovidedsupportwasdesignedtobenatural,ifnotexpected:Supportwasprovidedimmediatelyfollowingtheparticipant’susuallypoordeliveryofashortpracticespeechandimmediatelypriortotheanticipatedrealspeech.Thusthesupportwasintendedtobeareasonableresponsebyapeertotheparticipant’sdifficultiesincopingwithapersonallymeaningfulstressor.

Supportvisibilitywasmanipulatedbyhavingtheconfederatepeeraddressthesupportcontent,whetherpractical(e.g.,advice)and/oremotional(e.g.,reassurance),either(a)directlytotheparticipantsuchthatitwouldbeinterpretedasasupportiveact(visible)or(b)indirectlyasaquerytotheexperimentersuchthatitwouldbehelpfultotheparticipantbutnotperceivedassupport(invisible).Theoutcomevariable,emotionalreactivitytothestres-sor,wasmeasuredasachangeindistressfromthebeginningofthestudy,whenparticipantswereunawareofitsspecificpurpose,toimmediatelyafterthesupportmanipulationandimmediatelypriortotheanticipatedspeech.

Inourexperiments,werestrictedourfocustofemalepartici-pantsandfemalepeerconfederates.Althoughthislimitsgeneral-

EFFECTSOFSUPPORTVISIBILITY

461

izability,wewishedintheseinitialexperimentstoavoidcross-sexinteractionsinwhichsupportprovisioncouldpossiblybeinter-pretedbyparticipantsasdisplayingromanticorsexualinterestonthepartoftheconfederate(asinthecaseinwhichClark&Mills,1979,usedmaleparticipantsandfemaleconfederatestostudydesireforacommunalrelationship).Inaddition,pastresearchershavedemonstratedthatgendercompositionisanimportantmod-eratoroftheeffectsofsupportreceipt(Derlega,Barbee,&Win-stead,1994;Winsteadetal.,1992).Afinalreasonforrestrictingourinitialexperimentstowomenwasbecauseoftheargumentthatwomen’sreactionstostressorsrelymoreonsupportgivingandreceiving,namely,the“tendandbefriend”response,ratherthanthe“fightorflight”responsemorecharacteristicofmen(Tayloretal.,2000).

Study1usedatwo-groupsdesignandcomparedtheeffectsofvisibleandinvisiblepracticalsupportondistress.Study2com-paredtheeffectsofvisibleandinvisibleemotionalsupportondistressandincludedano-supportcontrolgroup.Study3wasdesignedtoexaminemediatingfactorsthatcouldaccountfordifferentialeffectsofvisibleandinvisiblepracticalsupport.

Study1

Webeganbyfocusingonvisibilityeffectsforpracticalsupportbecausepriorexperimentalresearchhadshownthatsuchsupporthadself-esteemcosts(i.e.,Fisheretal.,1982;Nadleretal.,1983).Wehypothesizedthatwhenfacedwiththeprospectofgivingastressfulspeech,thoseparticipantswhoobtainedadviceonpublicspeakingindirectlyandinvisiblywouldexperiencelessanticipa-torydistressthanwouldthosewhoobtaineditdirectlyandvisibly.

Method

Participantsanddesign.Thirty-fivefemaleparticipantswererecruitedfromtheNewYorkUniversityundergraduateparticipantpool.ParticipantswereallIntroductiontoPsychologystudentswhoparticipatedinstudiesaspartoftheircourserequirement.Participantswererandomlyassignedtothetwoconditions,whichresultedin18beinginthevisiblesupportconditionand17intheinvisiblesupportcondition.However,4participantslaterreportedbeingsuspiciousaboutthecoverstoryandweredroppedfromanalyses.Thisresultedinafinalsampleof31,with16inthevisiblesupportconditionand15intheinvisiblesupportcondition.Themeanageofincludedparticipantswas19.3years(SD?2.9).Theethnicitybreakdownwas58%Caucasian,16%Hispanic,13%Asian,7%AfricanAmerican,and6%other/unknown.

Theexperiments,includingthedebriefing,tookapproximately20mintocomplete.Studies1and2usedalmostidenticalproce-duresandmeasures.Participantswerestudentswhosignedupforapurportedstudyonteacher–studentinteractionsentitled“BetterGrades.”Theyweregreetedinthepsychologydepartmentwaitingareabyafemaleexperimenteranddiscoveredthatanotherfemalestudentinthewaitingarea(inreality,theconfederate)wouldbejoiningthemintheexperiment.Allconfederateswerecasuallydressedwomenintheirearly20s.Theexperimentersweremoreformallydressedwomenintheirlate20s.Beforedeliveringthefullcoverstory,theexperimenteradministeredabaselinequestion-nairetotheparticipantandtheconfederatepeer.

Aftertheycompletedthebaselinequestionnaire,theexperi-mentertoldtheparticipantandconfederatethattheresearchteam

wasstudyinggradingbiaseffectsandthatbothofthemwouldperformacademictasksthatwouldbeevaluatedbygraduateteachingassistants.Onestudentwouldgiveaspeechandtheotherwouldwriteanessay.Theexperimenterexplainedthatthepurposeoftheexperimentwastocomparetwoevaluationsofstudents’performance:Onegraduateassistantwouldseestudents’demo-graphicandgradeinformationfromtheirbaselinequestionnairesandasecondgraduateassistantwouldnot.

Theexperimentertheninformedtheparticipantandconfederatepeerthatthroughrandomassignmenttheparticipantwouldberequiredtogiveaspeechandherpeerwouldberequiredtowriteanessay.Bothweretoldthatthetopicfortheirrespectivetaskswouldbetheonetheyhadidentifiedaspersonallyimportantinthebaselinequestionnaire.Theywerealsotoldthattheexperimenterswereseeingstudentsinpairssothatthestudentassignedtotheacademicessaytask(theconfederate)couldactasapracticeaudiencewhiletheotherstudentcomposedherspeechaloud.Followingtheseinstructions,theparticipantwasgiven5mintopracticeherspeech.Withoutexception,participantsweredis-mayedtohearthattheyhadbeenassignedtogiveaspeech,butallproceededwiththepracticephaseoftheexperiment.Giventhebriefperiodallottedtopractice,fewparticipantsmanagedtoproduceapolishedversionoftheirspeech,andalmostallappearedunhappywiththeirpracticeefforts.

Thesupportmanipulation(describedbelow)occurredafterthepracticeperiodwascomplete.Followingthesupportmanipulation,theconfederatelefttheroomto(supposedly)writeheressay.Afinalshortquestionnairewasthenadministeredtotheparticipant,afterwhichshewasledtobelieveshewouldgiveherspeech.Atthispoint,theparticipantunderwentasuspicioncheck,followedimmediatelybytherevelationthatshewouldnot,afterall,havetogiveherspeech.Shewasthendebriefedandtheexperimentwasconcluded.Notethattheexperimentermovedtheexperimentalongatabriskpacethroughouttopreventunscriptedinteractionbetweentheparticipantandconfederate.

Becausetheexperimentinducedconsiderabledistress,partici-pantswentthroughextensivedebriefingaccordingtorecommen-dationsbyMills(1976)forexperimentsusingdeceptionand/orstress.Theexperimenterdescribedthetruehypothesesandex-plainedthatdeceptionwasnecessaryinordertoinducefeelingsofstressintheparticipantandtomanipulatesupportvisibility.

Variablesandmeasures.Boththebaselineandfinalquestion-nairesweretwopageslong.Inadditiontothemeasuresdescribedbelow,thebaselinequestionnaireincludeddemographicquestionsandthemeasureoftopicandtaskimportance.Forthelatter,theinstructionread:“Hereisalistofcurrentissuesorconcerns.Pleasecheckoneissuethatismostimportanttoyou—orwriteinyourown.”Participantschosefrom“abortion,”“homelessness,”“drugs,”“AIDS,”or“other.”Theselectionwasthenratedforpersonalimportanceona5-pointscale(0?notatall;1?alittle;2?moderately;3?quiteabit;4?extremely).Itwaspartici-pants’choiceoftopicthatbecamethesubjectoftheiranticipatedspeechtask.Bothquestionnairesalsoincludedseveralitemswhosepurposewastomaintainthecoverstory(e.g.,“Peoplegetthegradestheydeserve”;“Teacherstendtofavorcertainstudents”).Supportprovision.Asnotedearlier,thesupportmanipulationoccurredfollowingthepracticeperiodandimmediatelybeforetheconfederatepeerlefttheroom(supposedlytowriteheressay).Thesupportbehaviorsweredesignedtoappearcredibleandnorma-

462

BOLGERANDAMAREL

tivelyappropriategiventheconfederate’sroleasafellowstudentparticipantandtheexcessivedemandsoftheexperimentaltaskthatledittobestressfulforvirtuallyallparticipants.

Thesupportconditionswerecuedasfollows:Whenthepartic-ipantcompletedherpracticespeech,theexperimentersaid,“It’sabouttimeforbothofyoutodoyourtasks,”anddirectlyaddress-ingtheconfederate,theexperimentersaid“[Confederate],doyouhaveanyquestionsformebeforewemoveon?”Totheexperi-menter’squery,theconfederatemadeoneoftworeplies,eachrepresentingasupportvisibilitycondition.

Table1showsthescriptsfortheconfederatepeerreplies.Theadvicethatwasembeddedinthesereplieswasacommonspeakingtip,takenfromaninformalanalysisofprimersonpublicspeaking(e.g.,Carnegie,1990).Toreducethepossibilityofbias,theex-perimenterremainedblindtotheexperimentalconditionuntilaslateaspossibleintheexperiment,specifically,untilaftertheparticipanthadbegunherpracticespeech.Atthispoint,theex-perimenterconsultedanassignmentsheetthatspecifiedthecon-ditiontobeimplemented.Theconfederatepeer(whowasblindtotheexperimentalhypotheses)wasblindtotheexperimentalcon-ditionuntilimmediatelypriortothesupportmanipulation,whenshewascuedbyacoversheetgiventoherbytheexperimenter.Inthevisiblesupportconditiontheconfederatepeeraddressedthepublicspeakingtipdirectlytotheparticipant,whereasintheinvisibleconditionsheaddressedittotheexperimenterintheformofaquestion.Confederateswereextensivelytrainedtobeconsis-tentintheirdeliveryandtoprojectawarm,benevolentmanner.Theirvocalintonationinthevisiblesupportconditionreflectedsuchasupportiveattitudesoastoavoidthepossibilityofinsultingordemeaningtheparticipant.

Themanipulationcheckforpracticalsupportvisibilitywastheitem“Mypartnerofferedmeinformationoradvice,”whichwasembeddedinthefinalquestionnaireaspartofa12-itemchecklist.Theinstructionsaccompanyingthechecklistwere“Pleasecheckalleventsthatoccurredduringthepracticeperiod.Checkallthatapply.”Theremainingchecklistitemswereorientedtothecoverstory(e.g.,“Ipicturedmyselfgivingtheactualtalkwhilepractic-ing”;“Ilearnedsomethingaboutmyselformytopic”).

Emotionalreactivity:Changeindistress.Distresswasmea-suredinthebaselineandfinalquestionnaireusingsixitemsfromtheProfileofMoodStates(Lorr&McNair,1971).TheProfileofMoodStatesisawell-validatedmeasureofmood,andithasbeenshowntoreliablydetectstress-relatedchangeswithinpersonsinarangeofmoods,includinganxiety,depression,anger,fatigue,andvigor(Cranfordetal.,2006).ThesixitemscomprisedthethreethatloadedhighestontheAnxietyandDepressionsubscalesinvalidationworkoncollegestudents(seeLorr&McNair,1971).

Participantsreadthefollowinginstructions:“Hereisalistoffeelingsorexperiences.Pleaseratehowyoufeelrightnow.”Eachitemwasratedbyparticipantsona5-pointscalewithlabelsnotatall,alittle,moderately,quiteabit,andextremely.

Participants’ratingsoneachitemweremappedontoa0–10scale,onwhich0representedaratingofnotatalland10representedaratingofextremely.Adistressscorewasthencom-putedbytakingthemeanofallsixitems.Thusascoreof0representedthelowestpossibleratingofdistressandascoreof10representedthehighestpossiblerating.Tocalculatehowdistress-ingtheanticipatedspeechtaskwasforparticipants,weusedasimplechangescore,subtractingtheirbaselinedistressfromtheirfinaldistress.Inthiswaystressorreactivitywascalculatedrelativetoeachparticipant’sownbaseline.Coefficientalphasforbaseline,final,andchangeindistresswere.74,.84,and.75,respectively.Althoughconcernshavelongbeenvoicedaboutthetypicallylowreliabilityofchangescores(e.g.,Cronbach&Furby,1970),suchlowreliabilityisnotinevitable,particularlyinstudiesinwhichthedesignislikelytoproduceappreciablechangeandthemeasuresaresensitivetochange(Cranfordetal.,2006;seeTaris,2000,Chapter4,foradiscussionoffactorsaffectingthereliabilityofchangescores).

ResultsandDiscussion

Manipulationchecksonexperimentalconditions:Taskimpor-tance,taskstressfulness,andpracticalsupportvisibility.Recallthattheexperimentwasdesignedtohaveparticipants(a)expecttogiveaspeechonatopicthatwasimportanttothem,(b)experienceariseindistressinanticipationofgivingthespeechtoanevalu-ativeaudience,and(c)interpretapeer’sbehavioraseithersup-portive(visible)ornot(invisible).Belowweprovideevidenceonoursuccessinachievingtheseconditions.

Regardingtaskimportance,participantsratedthetopicoftheirspeechas“quiteabit”importanttothem,averaginga3.26outof4(95%confidenceinterval[CI]?3.09,3.43;allsubsequentCIsreferto95%coverage).Asexpectedgivenrandomassignment,therewasnosignificantdifferenceintaskimportancebetweenthetwosupportconditions,t(29)?0.10,p?.919.

Clearevidenceemergedthatthetaskwasperceivedasstressful.Facedwiththeprospectofdeliveringahastilypreparedtalktobeevaluatedbytwograduatestudents,thetypicalparticipant’sdis-tressrosefromherbaselinelevelof2.29unitsona0–10scale(SD?1.76,CI?1.64,2.93)to4.34unitsimmediatelybeforesheexpectedtodeliverthetalk(SD?2.43,CI?3.45,5.23),pairedt(30)?5.44,p?.0001.Thiscorrespondstoastandardizedeffect

Table1

Study1PeerSupportConditionsFormedbyConfederatePeer’sResponsetoExperimenter’sQuestion“DoYouHaveAnyQuestionsforMeBeforeWeMoveon?”

ConditionVisibleInvisible

Peer’sresponse

“Notreally.ButIwouldliketosaysomethingto[Participant]ifthat’sallright.Youknow,togiveagoodtalkit’sprobablymostimportanttosummarizewhatyou’regoingtosayatthebeginning,andalsotomakeastrongconclusionattheend.”

“Yes,I’vegotaquestionaboutwhatwe’resupposedtobedoing.Ithoughtthatforthiskindofthing,it’sprobablymostimportanttosummarizewhatyou’regoingtosayatthebeginning,andalsotomakeastrongconclusionattheend?”

EFFECTSOFSUPPORTVISIBILITY

463

size(J.Cohen,1988)of1.04SDunits1(CId?0.65,1.43).GiventhatCohenrecommendedthateffectsof0.2SDunitsbelabeled“small,”.5belabeled“medium,”and.8belabeled“large,”itcanbeseenthateventhelowerboundoftheCI(0.65)isinthemedium-to-largerange.Consistentwithrandomassignmenttocondition,therewerenoinitialdistressdifferencesbetweencon-ditions,t(29)?1.08,p?.286.

Themanipulationcheckforpracticalsupportvisibilityshowedthatall15participantsinthevisiblesupportconditionreportedreceivingsupport(i.e.,inthefinalquestionnairetheycheckedtheitem“Mypartnerofferedmeinformationoradvice”),whereasnoneofthe16participantsintheinvisiblesupportconditiondidso.

Effectofsupportvisibilityonchangeindistress.Ourhypoth-esiswasthatinvisiblepracticalsupportwouldhaveamoreame-liorativeeffectondistresscomparedwithvisiblepracticalsupport.Totestthishypothesis,weexaminedwhetherpremanipulationtopostmanipulationincreasesindistressweresmallerfortheinvis-iblesupportcondition.Todecreasetheerrorvarianceagainstwhichtheexperimentaleffectwouldbeassessed(andtherebyincreasestatisticalpower),weincludedinitiallevelofdistressasastandardexperimentalcovariate.Thehypothesiswasconfirmed:Participants’distressroseconsiderablylesswhensupportwasinvisiblecomparedwithwhenitwasvisible.Adjustingforinitiallevelofdistress,wefoundthatdistressrose1.05units(CI?0.10,2.00)forparticipantsintheinvisiblesupportcondition,whereasitrose3.13units(CI?2.15,4.12)forthoseinthevisiblesupportcondition.Thisthree-folddifferenceintheoriginalunitscorre-spondstoalargeeffectinstandarddeviationunits(d??1.09,2CId??1.81,?0.37),t(28)?3.10,p?.004.3Thelowerboundestimateoftheeffectwassubstantiallysmallerbutstillinthesmall-to-moderaterange(?0.37).

Althoughthispreliminaryexperimentestablishedthefeasibilityofmanipulatingsupportvisibilityinalaboratorysettingandpro-ducedresultsconsistentwiththeBolgeretal.(2000)nonexperi-mentalfindings,itleftbasicquestionsunanswered.Werethegroupdifferenceswefoundattributabletobeneficialeffectsofinvisiblesupport,deleteriouseffectsofvisiblesupport,orboth?Wouldtheresultsfoundforpracticalsupportalsoapplytoemo-tionalsupport,theothermajorformofsupportexaminedintheliterature?

Study2

Toaddressthesequestions,inStudy2weincludedano-supportcontrolcondition,andweexaminedwhethersupportvisibilityeffectscouldbeshownforemotionalsupport.Wehypothesizedthatinvisiblesupportwouldbebeneficialcomparedwithnosup-portbecausewhensupportismadeinvisibletotherecipientthebenefitsofthesupportcontentareaccruedandthecostsofsupportawarenessareavoided.Bythesamelogic,wehypothesizedthatforvisiblesupportthebenefitsofthesupportcontentwouldbeoffsetbythecostsofsupportawareness,perhapsleavingrecipientsnobetteroffthaniftheyhadnotreceivedsupportatall.

Method

Study2differedonlyslightlyfromStudy1intermsofmeth-odology.Thesamemeasureswereused4and,forthemostpart,the

experimentalprocedurewasidentical.ThefollowingdescribesonlythewaysinwhichitdeviatedfromStudy1.

Ninety-sixfemaleparticipantswererecruitedovertwosemes-tersatNewYorkUniversityaspartofacourserequirementforIntroductiontoPsychology.Fiveparticipantsdidnotcompletetheexperimentbecausetheyfoundtheprospectofgivingaspeechtoodistressing.Allbut1droppedoutpriortothepracticeperiodandbeforesupportwasmanipulated.Additionally,basedonthesus-picioncheck,5otherparticipantsweredroppedfromthestudy(theseparticipantswerenotconcentratedinanyparticularexper-imentalcondition).Thefinalsampleconsistedof86participants,ofwhom29wereinthevisiblesupportcondition,27wereintheinvisiblesupportcondition,and30wereinthenosupportcondi-tion.Themeanageofincludedparticipantswas18.9years(SD?1.0),andtheethnicitybreakdownwasCaucasian,60%,Asian,14%,Hispanic,13%,AfricanAmerican,10%,andother/unknown,4%.

Ouroperationalizationofemotionalsupportprovisionwastohavetheconfederatepeertelltheparticipantthatshehad“nothingtoworryabout,thatshewoulddofine.”Inthevisibleemotionalsupportconditionthisopinionwasexpresseddirectlytothepar-ticipant.Intheinvisibleemotionalsupportcondition,theconfed-erateexpressedthisopinionoftheparticipantaspartofaquestiontotheexperimenterabouttheconfederate’stask.Inthenosupportcondition,theconfederatedidnotrefereitherdirectlyorindirectlytotheparticipant.ThespecificwordingusedineachconditionisshowninTable2.

ResultsandDiscussion

Manipulationchecksonexperimentalconditions:Taskimpor-tance,taskstressfulness,andemotionalsupportvisibility.Wefirstpresentdatashowingthattheexperimentalconditionsoftaskstressfulness,taskimportance,andsupportvisibilityversusinvis-ibilityweremet.Regardingtaskstressfulness,averagingoverthesupportconditions,participants’distressrose1.60unitsona0–10scalefrombaseline(M?2.06,SD?1.92,CI?1.65,2.48)tofinallevels,M?3.66,SD?2.38,CI?3.15,4.17),pairedt(85)?6.65,p?.0001(d?0.78,CId?0.54,1.01).Asanticipated,initialdistressdidnotdifferacrossconditions,F(2,83)?1.54,p?.220.

AsinStudy1,theaverageparticipantratedthetopicofherspeechasbeingbetween“quiteabit”and“very”importanttoher

1

InthiscaseweusedaversionofCohen’sdadaptedforwithin-subjectscomparisons,aversioninwhichthestandarddeviationestimatecombinedbothbetween-andwithin-subjectvariance(seeMaxwell&Delaney,2004,pp.547–550).2

AsrecommendedbyMaxwellandDelaney(2004,pp.431–434),weusedastandarddeviationestimatethatdidnotremovevarianceduetothecovariate.3

Anadditionalanalysiswithoutcovaryinginitialdistressproducedresultswithalmostidenticalmeandifferences,slightlylargerstandarderrors,andslightlylargerprobabilities.Thisistobeexpected:Giventhatrandomassignmentresultedininitialdistressbeingunrelatedtosupportcondition,initialdistressfunctionedasastandardexperimentalcovariateandincreasedstatisticalpower(seeKutner,Nachtsheim,Neter,&Li,2005,pp.939–940foraconcisediscussionofthisissue).NotethatasimilarpatternwasfoundforStudy2andStudy3.4

InStudy2,coefficientalphasforbaseline,final,andchangeindistresswere.84,.89,and.83,respectively.

464

BOLGERANDAMAREL

Table2

Study2PeerSupportConditionsFormedbyConfederatePeer’sResponsetoExperimenter’sQuestion“DoYouHaveAnyQuestionsforMeBeforeWeMoveon?”

ConditionPeer’sresponse

Visible

“Notreally.ButIwouldliketosaysomethingto[Participant]ifthat’sallright.Look,you’vegotnothingtoworryabout,you’lldofine.I’dunderstandifyouwerenervous,butIreallythinkit’sgoingtobeokay.”

Invisible

“Yes,canyoutellmemoreaboutwhatI’mdoing?Imean,[Participant]isgoingtodofine,she’sgotnothingtoworryabout,butIstilldon’tknowwhatI’msupposedtodo.”Nosupport

“Notreally.Unlessyou’regoingtotellmemoreaboutwhatI’msupposedtodo?”

(0–4scale;M?3.3,SD?0.5).Therewerenosignificantdifferencesintaskimportanceacrossconditions,F(2,83)?1.72,p?.14.Themanipulationcheckforemotionalsupportreceipt(embeddedinthe12-itemchecklistinparticipants’finalquestion-naire)was“Mypartnerofferedmereassurance.”Allbut1partic-ipantcheckedthisiteminthevisiblesupportcondition(28of29),andallbut1didnotcheckitintheno-supportcondition(1in30).However,onequarterofparticipantsintheinvisiblesupportcon-ditioncheckedit(7of27).Becausewewereconcernedthattheinclusionofthese7participantsmightaffectthemainresults,weranallsubsequentanalysestwice,oncewiththemincludedandoncewiththemexcluded.Becauseinclusionorexclusionhadnoeffectonthefindingswepresenttheresultsforthecompletesample.

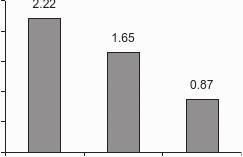

Effectofsupportvisibilityonchangeindistress.AsFigure2illustrates,distressroseleastintheinvisiblesupportcondition(0.87units;CI?0.07,1.66),whereasitrosemostinthevisiblesupportcondition(2.22units;CI?1.46,2.98).Participantsinthenosupportconditionshowedanintermediaterise(1.65units;CI?0.90,2.39).Aone-wayanalysisofcovariance(ANCOVA)withinitialdistressasacovariatewasusedtoanalyzethesedifferences.AplannedcomparisonoftheinvisibleversusvisibleconditionreplicatedtheresultfoundinStudy1,Mdiff.??1.35,d??0.63,CId??1.15,?0.12,t(82)??2.43,p?.017,withthequalifi-cationthatinthiscasetheeffectsizewassmaller(?0.63vs.?1.09)anditslowerboundvaluewassmall(?0.12)ratherthansmalltomoderate(?0.37).

Aplannedcomparisonoftheinvisibleandnosupportconditionsrevealedaneffectinthepredicteddirection,withparticipantsintheinvisibleconditionshowinglowerincreasesindistressthanthoseinthenosupportcondition.AlthoughtheCIfortheeffectincludedalargebenefit,itwassufficientlywidethatitincludedzeroandevenasmalleffectintheoppositedirection,M?0.78,d??0.36,CI(82)??1.42,p?diff..159.?d??0.88,0.15,tForthethirdplannedcomparison,visibleversusnosupport,recallthatwepredictedanullorpossiblydeleteriouseffect.Ourresultswereconsistentwiththisprediction,butagaintheconfi-denceintervalwaslarge,rangingfromalargedeleteriouseffecttoasmallbeneficialeffect,Mdiff.?0.57,d?0.27,CId??0.23,0.76,t(82)?1.07,p?.287.

Thegoalsofthisexperimentwere,first,toreplicatetheresultsofStudy1usingemotionalratherthanpracticalsupportand,

second,toassesswhetherthisdifference,iffound,wasduetoabeneficialeffectofinvisiblesupport,adeleteriouseffectofvisiblesupport,orboth.Asshownabove,thefirstgoalwasmetinthatstressorreactivitywassignificantlygreaterforvisiblethaninvis-iblesupport.

Theresultsforthesecondgoalwerelessclearcut.Althoughtheobservedmeandifferencesindicatedabeneficialeffectofinvisiblesupport,theeffectsizewassmalltomedium,anditwasnotpossibletoruleoutanullorevenslightlydeleteriouseffect.Forvisiblesupport,theCIswerealsowide,rangingfromalargedeleteriouseffecttoanullorslightlybeneficialeffect.Note,however,thattherangeofvaluesnotcoveredbytheCIsstillpermitsustodrawinterestingandinformativeconclusionsaboutthevisibilityofenactedsupport:Visiblesupport,thecanonicalformstudiedinpriortheoryandresearch,hasatbestasmallbenefitcomparedwithnosupport,whereasinvisiblesupportislikelytohaveabeneficialeffectandhasatworstasmallnegativeeffect.

Study3

Inthethirdandfinalstudyusingthepeersupportparadigm,wemovedbeyonddemonstratingtheexistenceofsupportvisibilityeffectstoinvestigatingunderlyingexplanatorymechanisms.Giventhenatureoftheparadigmandtheresultsofthepriorstudies,wereasonedthatfourunderlyingfactorsneededtobedistinguished.Thesewere(a)presenceorabsenceofsupportcontentprovidedbythepeer(inStudy3wereturnedtothecontentexaminedinStudy1,i.e.,advice),(b)itsvisibilitytotherecipient,(c)whetheritcommunicatedinefficacyintherecipient,and(d)whetheritcom-municatedinefficacyinthepeersupportprovider.Byconsideringthesefactorswithinasingleresearchdesign,thefollowingques-tionscouldbeaddressed.

First,therewasthequestionofwhethervisiblesupportwasrelativelydetrimentalbecauseitnecessarilycommunicatedafeel-ingofinefficacytotherecipientandtherebyoffsetanybenefitofthesupportcontent.AnopponentprocesssuchasthishadbeenaworkingexplanatoryhypothesissincetheoriginalfindingsofBolgeretal.(2000)andthebroadersetofanalysesofShroutetal.(2006).Weviewedthiscommunicationofinefficacyasanun-avoidablefeatureofvisiblesupportinteractions.Thishypothesisrestedonpriortheoreticalworkthatemphasizedhowtheself

is

2.5e

g2.0nahc1.5 sser1.0tsiD0.50.0

VisibleNo SupportInvisible

Support Condition

Figure2.Study2:Effectsofpeersupportvisibilityconditionsondistresschange(0–10scale).Thestandarderrorforeachmeanisapproximately.39units.

EFFECTSOFSUPPORTVISIBILITY

465

formedandmaintainedbythereflectedappraisalsofothers(Cooley,1902/1983;Stryker&Statham,1985),bypriorexperi-mentalworkshowingthathelpinego-relevantdomainscouldhaveself-esteemcosts(e.g.,Fisheretal.,1982),andmoregenerally,bypriorworkshowingthatthenegativeeffectsofsupportaremedi-atedbyself-relevantjudgmentssuchascompetenceandefficacy(Newsom,1999).Weinvestigatedthisideabycreatingamodifiedvisiblesupportcondition,onethatdidnotinvolvethecommuni-cationofinefficacy.

Second,therewasthequestionofwhethertheinvisiblesupportconditionwasrelativelybeneficialbecauseitscontentwascom-municatedindirectlyorbecausethepeerhighlightedherownsenseofinefficacyandtherebynormalizedtheparticipant’ssenseofbeinginefficacious.Wenotedintheintroductiontothearticlethatitwaspossiblethatskillfulpeersupportersusedthisstrategytoreducetherecipient’sdistress,andthatitwasplausiblethattheeffectmightoperatethroughreducingtherecipient’suseofup-wardsocialcomparisontothepeer.Althoughthelinkbetweensocialsupportandsocialcomparisonisarelativelyneglectedone(butseeBuunk&Hoorens,1992;Taylor,Buunk,&Aspinwall,1990),itseemedtoustobeveryrelevantforthistypeofindirectorinvisiblepeersupport.Ourworkinghypothesiswasthatinthecontextofthespeechstressor,upwardcomparisontoanapparentlymorepoisedandconfidentpeerwouldleadtoincreasesindistress.However,wenotethattheuseofupwardcomparisonisnotalwaysassociatedwithincreaseddistress,asinthecaseinwhichpartic-ipantshavethegoaloflearningfromthecomparisonperson(R.L.Collins,1996).

Athirdissuewaswhethertheactualcontentofthesupportwasimportantinreducingdistress.Inthepriortwoexperiments,thesupportcontent(advice,reassurance)hadbeenconfoundedwithvisibility,recipientinefficacy,andproviderinefficacy.Inthenewdesign,thesefactorswereunconfounded.Afinalandrelatedissue

waswhetherthevisibilityperseofthesupportwouldbeimportantindependentofotherfactors.Again,thenewdesignallowedustodisentanglesupportvisibilityfromsupportcontent,providerinef-ficacy,andrecipientinefficacy.

IncompleteFactorialDesignofExperiment3

Table3showstheparticularcombinationsofthefourfactorsweusedinStudy3.Ifallpossiblecombinationsoffactorshadbeenincluded,thedesignwouldhaveinvolved16cellsandaprohibi-tivenumberofparticipants.However,notallofthecellswereoftheoreticalinterestorwereevenlogicallysensible.Aswedetailbelow,weimplementedanincompletefactorialdesign,givingprioritytocontraststhat“peeledaway”componentsofwhatweregardedasstandardvisibleandinvisiblesupportconditions.Ourinferencesarenecessarilyconditionalontheincludedconditions.Wefirstexplaintherationalefortheincludedcellsandthenconsidertheexcludedones.

ThefirstconditioninTable3,VisibleA,iswhatcanbeviewedasastandardvisiblesupportinteractioninapeercontext.Itrepresentsspecificcombinationsofthefourfactorsintroducedearlier:(a)thepresenceofsupportintheformofadviceonpublicspeaking,(b)addresseddirectlytotherecipientandpresumablyvisibletoher,(c)thecommunicationthattherecipientneededhelpand/orwasinefficacious,and(d)theimplicationthatthepeerproviderwasnot.Thus,inresponsetotheexperimenter’srequestforquestionsorcomments,theconfederatepeerrepliedbynotingthattherecipientwasinneedofhelpanddirectedtheadviceonpublicspeakingtotherecipient.Also,givenitscontext—theexperimenter’squerywhetherthepeerhadanyquestionsforher—thepeer’sresponseimpliedthatsheherselfwasnotinneedofhelpwithherwritingtask.VisibleAwassimilartothevisibleconditionsusedintheprevioustwoexperiments,withtheexcep-

Table3

Study3PeerSupportConditionsFormedbyConfederatePeer’sResponsestoExperimenter’sQuestion“DoYouHaveAnyCommentsfor[Participant]orAnyQuestionsforMeBeforeWeMoveon?”

Contrast

ConditionVisibleA

PracticalsupportYes

VisibilityYes

RecipientinefficacyYes

PeerinefficacyNo

1●

2●

3

4

5

6

Peer’sresponse

“Well,Icantellthatyoucouldusesomehelp.Ithinkit’sbesttosummarizewhatyou’regoingtosayatthebeginningofaspeechandtoendwithadefiniteconclusion.”

“Well,Idon’tthinkthatyouneedanyhelp.But,ifIhadtosaysomething,I’veheardthatit’sbesttosummarizewhatyou’regoingtosayatthe

beginningofaspeechandtoendwithadefiniteconclusion.”

“Well,Idon’tthinksheneedsanyhelp,butIcouldusesomehelp.ShouldIstructuremyessayinacertainway?LiketosummarizewhatI’mgoingtosayatthebeginning,andtoendwithadefiniteconclusion?”

“Well,Idon’tthinkthatsheneedsanyhelp,andIdon’teither.I’lljustsummarizewhatI’mgoingtosayatthebeginningofmyessayandendwithadefiniteconclusion.”“No,notreally.”

VisibleBYesYesNoNo●●

InvisibleAYesNoNoYes●●

InvisibleBYesNoNoNo●●●

NosupportNo●●●

Note.Thesixplannedcontrastsareindicatedbyverticalpairsofbulletsinthenumberedcolumns:1?visiblesupport,2?recipientinefficacy,3?invisiblesupport,4?peerinefficacy,5?purevisibility,6?purecontent.

466

BOLGERANDAMAREL

tionthatthepeernowexplicitlynotedthattherecipientneededhelp.Theprecisescriptforthisconditionisdisplayedontheright-handsideofTable3.Aplannedcontrastofthisconditionwiththenosupportcondition(Contrast1:VisibleSupport),al-lowedustoobtainabenchmarkestimateofitseffect,onethatcouldbelatercomparedwithconditionsinwhichputativecom-ponentfactorsweremanipulated.

Specifically,thenextconditioninTable3,VisibleB,differedfromVisibleAonlybyhavingthepeerexplicitlysaythattherecipientdidnotneedhelp.ThescriptusedforVisibleBisalsodisplayedinTable3.ThusacontrastoftheVisibleAandBconditions(Contrast2:RecipientInefficacy)couldassesswhetherremovingtheinefficacycommunicationhadanyeffectonstressorreactivity.

Thenextcondition,InvisibleA,waswhatcanbeconsideredastandardinvisiblecondition.Itagainrepresentedspecificcombi-nationsofthefourfactorsintroducedearlier:(a)supportintheformofpublicspeakingadvice,(b)addressedindirectlytotherecipientandintendedtobeinvisible,(c)thecommunicationthattherecipientwasnotinneedand/orinefficacious,and(d)thecommunicationthatthepeerwas.Thus,inresponsetotheexper-imenter’squestion,thepeerstatedthattherecipientwasnotindifficultybutthatsheherselfwasandcommunicatedthesupportcontentasaquestiontotheexperimenter.ThisconditioncloselyapproximatedtheinvisibleconditionusedinStudy2,andweexpectedittoreduceemotionalreactivitywhencontrastedwiththenosupportcondition(Contrast3:InvisibleSupport).

TheInvisibleBconditionwasdesignedtobeformallyidenticaltoInvisibleA,withtheexceptionthatthepeersaidthatshewasnotinneed.ThusacontrastofInvisibleAandInvisibleBwasdesignedtoassesshowimportantthecommunicationthatthepeerfeltinefficaciouswasinproducingthebenefitsofinvisiblesupport(Contrast4:PeerInefficacy).

Thusfar,wehavediscussedfourplannedcontrasts.Afifthcontrastwasalsoplanned,onecomparingVisibleBandInvisibleB,asthesewereformallyequivalentexceptforvisibilityanddirectness(Contrast5:PureVisibility).Specifically,inbothcasestheinteractioncommunicatedthatneithertheprovidernortherecipientwasindifficulty,butinthevisiblecasethesupportcontentwasdirectedtotheparticipant.

Thefinalplannedcontrastwasdesignedtoassesstheimpor-tanceofthesupportivecontent(Contrast6:PureContent).InthiscasetheInvisibleBconditionwascontrastedwiththenosupportcondition.Intermsofthefactorialdesigntheseweresimilarintermsofrecipientinefficacy,peerinefficacy(bothwerelow),anddirectness(bothwereindirect),butdifferedincontent.

Itisimportanttopointoutthatasaresultofthepatternofincompletenessinthedesign,theselattertwocontrastswerelesstheoreticallyinformativethanthefirstfour.Specifically,thePureVisibilityandthePureContentcontrastscouldonlybeassessedwhenbothrecipientandpeerinefficacywerelow.Thislimitationreflectedourplacinggreaterweightonassessingtheroleofinefficacycommunicationasexplanatoryvariablesfortheeffectsfoundintheearlierstudies.

Wenowturntotheomittedcellsinthedesign.First,inacompletelycrosseddesigntherewouldhavebeeneightnosupportcellsratherthanone.Weexcludedfouroftheeightbecausewhennosupportisprovideditmakesnosensetotalkofthedirectnessand/orindirectnessofitsdelivery.Weeliminatedthreemorebecausewedidnotseethevalueofcreatingconditionsinwhichno

supportcontentwasprovidedbutproviderand/orrecipientineffi-cacywascommunicated.Thefinalfourmissingcellsrepresentparticularcombinationsofvisibility,providerinefficacy,andre-cipientinefficacy.Oftheseonlytwomadetheoreticalsense:Bothproviderandrecipientwereinneed,andthesupportcontentwaseithervisibleorinvisible.WeargueintheDiscussionsectionthatthetheoreticalyieldofthesecellswasnotsufficientlygreattojustifytheadditionaldesigncomplexity.

AssessingMediatingProcesses

Theorytestinginvariablyinvolvestheassessmentofmediatingprocesses(Brewer,2000;Cook&Groom,2004;Smith,2000).Onceanexperimentaleffecthasbeendemonstrated,thereareatleastthreemainwaysinwhichmediationcanbeassessed.Thefirstistoconductstudies(a)thatshowthattheexperimentalmanipu-lationaffectsthemediatorand(b)inwhichindependentlymanip-ulatingthemediatoraffectsthedependentvariable(Cook&Groom,2004).Thesecondistouseexperimentalcontroltoholdtheputativemediatorconstantand,bydoingso,blocktheexper-imentaleffect(Brewer,2000).Thethirdistousethestatisticalmodelingtechniqueofmediationalanalysis(Baron&Kenny,1986;Hoyle&Robinson,2004;Kenny,Kashy,&Bolger,1998;Shrout&Bolger,2002).Inprinciple,thelattertwoapproachescanbeusedinthesamestudy,andweusedthisstrategytoinvestigatepotentialmediatorsofsupportvisibilityorinvisibilityeffects.Wereasonedthatevidenceofmediationthatemergedinbothap-proacheswouldbeparticularlycompelling.5

Theplannedcontrastsdescribedearlierfocusonexperimentalcontrolofputativemediators,butwealsomeasuredrelevantmediatorstoassesswhethertheexperimentalconditionsdifferedinpredictedwaysonthemediatorsandwhetherthesemediators,inturn,explaineddifferencesinrecipientdistress.Weincludedmea-suresofmediatorsthatwouldbeexpectedtovaryasafunctionoftheexperimentalmanipulations,namely,theparticipant’sreflectedappraisalsoftheirinefficacy(alikelymediatoroftheVisibleSupportcontrast,giventhecommunicationofinefficacyinherentinthestandardvisiblesupportcondition)andtheparticipant’sreducedtendencytouseupwardsocialcomparisontoherpeer(alikelymediatoroftheInvisibleSupportcontrast,giventhatthepeer’scommunicationofherinefficacyshouldreducethepartic-ipant’ssenseofbeinginaworsesituationthanherpeer).

Method

Participantsanddesign.Onehundredsixty-sevenfemalepar-ticipantswererecruitedovertwosemestersatNewYorkUniver-sityaspartofacourserequirementforIntroductoryPsychology.Participantswereeachrandomlyassignedtooneofthefivesupportconditions.Fiveparticipants(3%)droppedoutpriortothesupportmanipulationbecauseofstress.Twelveparticipants(7%)weredroppedfromtheanalysesbecauseofsuspicion.Thesesuspiciousparticipantswerenotconcentratedinanyonecondition.Themeanageoftheremaining150participantswas20.27years(SD?1.69),andtheethnicitybreakdownwasasfollows:Cau-casian(53%),AfricanAmerican(7%),Hispanic(11%),EastAsian

5

SeeSpencer,Zanna,andFong’s(2005)recentarticleonconditionsunderwhichchoosingoneapproachispreferabletotheothers.

EFFECTSOFSUPPORTVISIBILITY

467

(13%),otherAsian(5%),AmericanIndian(1%),other(11%).Thebasicprocedurewaslargelysimilartothatusedintheprevioustwoexperiments.Belowwegivedetailsononlythenovelaspectsofthecurrentexperiment.

Supportprovision.Inthisexperimentthesupportprovidedwaspractical,namelytheadviceof“summarizingwhatyouaregoingtosayandendwithastrongconclusion.”Asinearlierexperiments,thesupportmanipulationoccurredfollowingthepracticeperiod,justbeforetheconfederatelefttheroom.Tojustifytheinclusionofseveralquestionnaireitemsabouttheconfederate(tobeusedasmediators),theexperimentercreatedaminimalexpectationthatsupportmightbeoffered.Duringherexplicationofthecoverstory,shetoldtheconfederate,“Afterthepracticeperiodyou’llgetachancetorespondifyouwantto.Butthenyou’llneedtodoyourowntask,okay?”

Thesupportconditionswerecuedasfollows:Uponcompletionofthepracticeperiod,theexperimentersaid,“It’sabouttimeforbothofyoutodoyourtasks....[Confederate],doyouhaveanycommentsfor[participant]oranyquestionsformebeforewemoveon?”Totheexperimenter’squery,theconfederatemadeoneoffivereplies;theseresponseswerethesupportmanipulation.SeeTable3fortheconfederate’sscriptforeachofthefivesupportconditions.Notethateachconditioncontained30participants.Asinthepreviousexperiments,themanipulationcheckforsupportvisibilitywasincludedinthefinalquestionnaire,embed-dedinthiscaseinan8-itemchecklistofexperiencesduringthepracticeperiod.Inaddition,thefinalquestionnaireincludedamoregeneralevaluationofhowhelpfulandwell-intentionedtheproviderappearedtotherecipient.Themeasure,partnersupport-iveness,wascomposedofameanof3items:“concerned,”“help-ful,”“supportive”(??.85).Theitemswereincludedinaten-itemlistofadjectivesdescribingthestudentpartner.Theinstructionread:“Hereisalistofwordsdescribingyourstudentpartner.Pleaseratehowwellthesewordsdescribehimorher.”Thefiveresponsecategorieswere“notatall,”“alittle,“moderately,”“quiteabit,”“extremely.”Tofacilitateinterpretationofresults,particu-larlyforthemediationalanalyses,werescaledthisandallotherratingscalestoa0–10interval,onwhichthelowestordinalcategorywascoded0andthehighestwascoded10.

Performanceexpectation.Becauseinpriorexperimentswehadnotedconsiderablebetween-personsvariabilityindistressamongparticipantswhentheylearnedthattheyweretogiveaspeech,weincludedperformanceexpectationasacontrolvariableinanalyses(seebelow).Itwasmeasuredusingameanoftwoitems,eachratedona5-pointscalethattheparticipantscompletedpriortotheirpracticetalk.Undertheinstruction“Pleaserateyouragreementrightnowwiththefollowingstatementsaboutyourupcomingtalk,”theitemswere“IexpectIwillgiveagoodtalk”and“Ifeelprettyconfidentaboutmytalk.”Theresponsecatego-rieswerestronglydisagree,disagree,neutral,agree,andstronglyagree.Thealphaforthemeasurewas.90.

Lengthofpracticespeech.Thiswasmeasuredtothenearestminute.Scoresrangedfrom1to5min,M?3.5min(SD?1.2min).Thiswasalsousedasacontrolvariable(seebelow).

Emotionalreactivity:Changeindistress.Distresswasmea-suredinthebaselineandthefinalquestionnairesandwascalcu-latedusingameanofnineitemsfromtheProfileofMoodStates.ThesewerethreeeachfromtheAnxiety,Depression,andAngersubscales.Thefiveresponsecategoriesrangedfromnotatalltoextremely.Theinstructionwas“Hereisalistoffeelingsor

experiences.Pleaseratehowyoufeelrightnow.”Thedependentvariable,distress,wasasimplechangescorefrombaselinetofinal(baseline??.88;final??.90;?change?.81).6

Reflectedappraisalofinefficacy.Ameanoftwoitemsinthefinalquestionnaire,ratedona5-pointscale,addressedhowmuchparticipantsfeltthatthepartnersawthemashavingaproblem(??.86).Thesewereincludedinalistofitemswiththefollowinginstruction:“Somepeopleprefertoworkalone,othersprefertoworkinpairsorgroups.Pleaserateyouragreementwiththefollowingstatementsaboutcomposingyourtalkwithapartner.”Thetworeflectedappraisalitemswere“MypartnerseemedtothinkIwasdoingfine”(reversed)and“MypartnerseemedtothinkIwashavingahardtime.”Theresponsecategorieswerestronglydisagree,disagree,neutral,agree,stronglyagree.

Upwardsocialcomparison.Participants’useofupwardsocialcomparisonstotheirconfederatepartnerwasmeasuredusingthemeanoftwoitemsinthefinalquestionnaire(??.67).Theinstructionsread:“Whenpreparingwithothers,feelingsaboutafriendorpartnermayaffectperformance.Pleaseratehowyoufeltwithyourstudentpartnerduringthepracticeperiod.”Theitemswere“lessknowledgeablethanhim/her”and“morenervousthanhim/her.”Thefiveresponsecategorieswerenotatall,alittle,moderately,quiteabit,andextremely.

ResultsandDiscussion

Herewepresentthreesetsofanalyses.First,weexaminewhetherthebasicexperimentalconditionsoftaskimportance,taskstressfulness,andsupportvisibilitywereestablished.Nextweexaminehowthefivesupportconditionsarerelatedtoparticipantreactivitytotheanticipatedspeechtask,includingplannedcon-trastsofparticularconditions.Finally,weexaminehypothesizedmediatorsoftheplannedcontrasteffects.

Manipulationchecksonexperimentalconditions:Taskimpor-tance,taskstressfulness,andsupportvisibility.Averagingacrossthesupportconditions,wefoundthatdistressrose0.92pointsona0–10scalefromthebaseline(M?1.77,SD?1.70)tothefinalassessment(M?2.69,SD?2.06),pairedt(149)?6.35,p?.0001,d?0.53,CId?0.37,0.72.Giventhatparticipantswererandomlyassignedtoconditions,wedidnotexpecttofinddiffer-encesinbaselinedistressamongthefiveconditions.Thedataconfirmedourexpectation,F(4,145)?0.92,p?.452.

Participantsratedthespeechtopicaspersonallyimportant.Theaveragescorefortaskimportancewas7.4ona0–10scale(SD?2.1),correspondingtoaverballabelof“quiteabitimportant.”Againtherewasnosignificantdifferenceintaskimportanceamongthefivesupportconditions,F(4,145)?1.01,p?.40.Table4presentstheresultsofthemanipulationcheckforsupportvisibilitybycondition.Overall,supportreceiptwasen-dorsedasexpected.Receiptwasrarelyreportedinbothinvisiblesupportconditions,neverreportedinthenosupportcondition,andalmostalwaysreportedintheVisibleAcondition.SixoftheparticipantsintheVisibleBcondition(20%),however,didnotreportreceivingsupport.Becauseremovingparticipantswhoseresponseswereinconsistentwiththeirconditiondidnotalteranyoftheresults,weusedthefullsampleinreportedanalyses.

6

Notethatmaineffectsofsupportvisibilityondistressweresimilarwhentheseparatesubscales(e.g.,Anxiety)wereeachtestedasthedepen-dentvariable.

468

BOLGERANDAMAREL

Table4

Study3ManipulationChecksforSupportVisibilityandPerceivedSupportiveness

SupportYes,naNo,nTotal

Supportivenessb

M(Range?0–10)

a

VisibleA291304.6

VisibleB246305.7

Nosupport030301.7

InvisibleB327302.5

b

InvisibleA129302.7Basedona

Basedonresponsestotheitem“Mypartnergavemeadviceortriedtocomfortme”[yes/no].meanofthreeitems:“concerned,”“helpful,”“supportive.”

Theresultsfortheoverallevaluationofpartnersupportiveness,showninTable4,wereconsistentwiththoseforthemanipulationcheckofsupportivebehavior.Participantsinthevisiblesupportconditionsratedtheconfederateasbeing“moderately”supportive(M?5.2,CI?4.6,5.7),whereasthoseintheinvisiblesupportconditionsratedherasbeing“alittle”supportive(M?2.6,CI?2.1,3.1).Thoseinthenosupportconditiongaveratingsmidwaybetween“notatall”and“alittle”(M?1.7,CI?0.9,2.4).Specificcontrastsindicatedthatthetwovisiblesupportconditionsweresignificantlymoresupportivethanthetwoinvisiblesupportconditions(Mdiff.?2.6,SE?0.4),t(145)?6.74,p?.0001,andthenosupportcondition(Mdiff.?3.5,SE?0.5),t(145)?7.42,p?.0001.Thepositivedifferencebetweentheinvisiblecondi-tionsandthenosupportconditionwasrelativelysmall,butitalsohadarelativelywideCI,(Mdiff.?0.9,SE?0.5,CI??0.03,1.8),t(145)?1.92,p?.057.Thus,atoneextremeitispossiblethattheconditionsdidnotdifferatall,andattheotherextremeitispossiblethattheinvisibleconditionswereratedalmost2unitsmoresupportivethanthenosupportcondition.

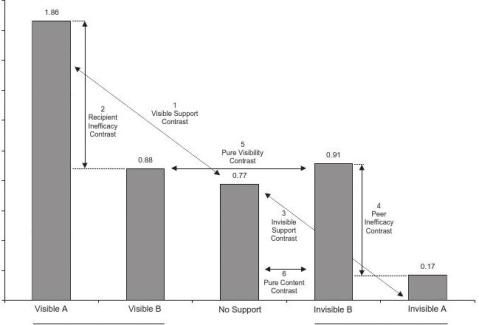

Effectsofsupportconditionsonreactivitytostress.Aone-wayANCOVAwithplannedcontrastswasusedtoanalyzethedifferencesinemotionalreactivitytothestressor.Weincludedthreecovariates,(a)initialdistress,(b)speechperformanceexpec-tation,and(c)lengthofpracticespeech.SpeechperformanceexpectationandlengthofpracticespeechwerenewmeasuresincludedinStudy3.Poorerperformanceexpectationsandlongerpracticespeecheswereassociatedwithincreaseddistress.Becausenoneofthecovariatesdifferedacrossthefiveconditionsandallofthemwererelatedtochangeindistress,theyfunctionedasclassicexperimentalcovariatesandincreasedstatisticalpower.Asex-pected,participantsinthefiveconditionsdifferedsignificantlyintheextenttowhichtheirdistresslevelsincreasedfromthebaselinetothefinalquestionnaire,F(4,142)?6.65,p?.001.Figure3showsabarchartoftheadjustedcellmeans.Figure3alsoincludesavisualdisplayoftheplannedcontrastsalreadydetailedinTable3.Contrast1:Visiblesupport(VisibleAvs.nosupport):Doesreceivingvisiblesupporthaveadeleteriouseffectonrecipientdistresscomparedwithreceivingnosupport?Theresultsessen-tiallyreplicatetheeffectfoundinStudy2.AsFigure3shows,theriseindistressforthoseintheVisibleAconditionwas1.09unitsgreaterthantheequivalentforthenosupportcondition(CI?0.43,1.75),t(142)?3.28,p?.001(d?0.66,CId?0.26,1.05).Contrast2:Recipientinefficacy(VisibleBvs.VisibleA):Canthedeleteriouseffectofvisiblesupportbereducedbyremovingthecommunicationofrecipientinefficacy?RecallfromTable3thatVisibleBandVisibleAdifferonlyinthecommunicationthattheparticipantisindifficultyandneedshelp.Ashypothesized,VisibleB,inwhichrecipientsareexplicitlytoldthattheyarenotindifficulty,islessdistressingthanVisibleA(M??1.65,0.99,??0.20.0.33),However,t(142)?diff.??0.99,CI?the2.95,resultingp?mean.004,ford?Visible?0.60,B(0.88)CId?isapproximatelythesameasthatforthenosupportcondition(0.77).Thus,althoughwesucceededincreatingavisiblesupportcondi-tionthatdoesnothaveanetupsettingeffect,ourremovalofthecommunicationthattherecipientisindifficultydidnotuncoveranunderlyingpositiveeffectofthesupportcontent(thatis,theadviceonpublicspeaking).

Contrast3:Invisiblesupport(InvisibleAvs.nosupport):Doesreceivinginvisiblesupporthaveabeneficialeffectonrecipientdistresscomparedwithnotreceivingsupport?Figure3showsthatparticipantsintheInvisibleAshowedanegligibleincreaseindistress(M?0.17,CI??0.30,0.63),whereasthoseinthenosupportconditionshowedalargerandsignificantincrease(M?0.77,CI?0.31,1.23).Aplannedcomparisonofthesemeans,however,failedtoreachsignificanceatthe.05level(M?0.61,?CI0.76,??0.03.1.26,The0.05),95%t(142)CIreveals?1.83,thatpthe?.069,populationd??diff.effect0.37,?CId?sizecouldrangefrom?0.76,alargebeneficialeffect,to.03,anulleffect.Althoughwecannotruleoutanulleffect,theCIisinlargemeasureconsistentwiththeideathatinvisiblesupportreducesstressorreactivity.

Contrast4:Peerinefficacy(InvisibleBvs.InvisibleA):Canremovingproviders’communicationoftheirinefficacyundothebeneficialeffectofinvisiblesupport?ThescriptsforthesupportconditionsinTable3showthatInvisibleBandInvisibleAdifferinwhetherthepeercommunicatedthatshewasindifficultyornot;theresultsinFigure3showthatInvisibleBissignificantlymoredistressingthanInvisibleA(0.91v.0.17,Mdiff.?0.75,CI?0.09,1.40),t(142)?2.25,p?.026,d?0.45,CId?0.05,0.84.ThemeanforInvisibleBisapproximatelythesameasthatforthenosupportcondition.Thus,removingthecommunicationthatpro-vidersareindifficultycompletelyundoesthebenefitsoftheinvisiblesupportcondition.Onemighthaveexpectedtoseere-maininganetpositiveeffectofthesupportcontentcommunicatedintheInvisibleBcondition.Wereturntothisissuebelow.

Contrast5:Purevisibility(InvisibleBvs.VisibleB):Incondi-tionsinwhichtheprovidercommunicatesthatneithershenortherecipientareindifficulty,issupportvisibilityperseimportant?AcontrastofVisibleBandInvisibleBshowsessentiallynodifference(0.88vs.0.91,Mdiff.??0.04,CI??0.62,0.37,0.69),t(142)?0.11,p?.915,d??0.02,CId??0.42,sug-gestingthatifrecipientandpeerinefficacyislow,thevisibilityofthesupportcontentdoesnotmatterforrecipientdistress.Unfor-tunately,becauseofthehighlyconditionalnatureofthiscontrast,

EFFECTSOFSUPPORTVISIBILITY

469

RsinDsatrnesDisitree ss cihgse

Yes

No

No

Yes

Recipient InefficacyPeer Inefficacy

Figure3.Study3:Effectsofpeersupportvisibilityconditionsondistresschange(0–10scale).Thestandarderrorforeachmeanisapproximately.23units.

itismoredifficulttointerpretthanthepreviousones.Itmaybethatvisibilitypersehasnoeffectingeneral,butitmayalsobethatvisibilityhasnoeffectwhenrecipientandpeerinefficaciesarelow.

Contrast6:Purecontent(InvisibleBvs.nosupport):Incon-ditionsinwhichtheprovidercommunicatesthatneithershenortherecipientareindifficulty,issupportcontentperseimportant?AcontrastofVisibleBandnosupportagainrevealsnodifferencebetweentheconditions(0.91vs.0.77,Mdiff.?0.14,CI??0.52,0.80),t(142)?0.42,p?.673,d?0.08,CId??0.31,0.48,suggestingthatincasesforwhichproviderandrecipientinefficacyislow,thecontentofthesupport,namely,theadviceonpublicspeakingdoesnotmatterforrecipientdistress.Althoughitmaybethatthespeakingadviceisofnovaluetotherecipient,thesamelimitationappliestothisresultastothepreviousone.

Insummary,basedontheplannedcontrastsoftheexperimentalconditions,itappearsthatremovingthecommunicationofrecipientinefficacyundoesthedeleteriouseffectoftheoriginalvisiblesupportconditionandthatremovingthecommunicationofproviderineffi-cacyundoesthebeneficialeffectoftheoriginalinvisiblesupportcondition.Aswesee,however,theseinterpretationsdonotcom-pletelyagreewiththemediationalanalysesthatwillfollow.

Mediationalanalyses.WeincludedinStudy3measuresofreflectedappraisalsofinefficacyandupwardsocialcomparisonsothatwecoulduseamediationalanalysis(Baron&Kenny,1986;Kennyetal.,1998)toseewhetherthesevariableshelpedexplainthepatternofresultsrevealedbytheplannedcontrasts.Notethatwedidnotconductthisanalysisforthefinaltwocontrasts(Invis-ibleBvs.VisibleB;InvisibleBvs.nosupport),astheserevealednegligiblemeandifferences.

Tounderstandthewaythemediationalanalyseswerecon-ducted,itisusefultothinkoftheone-wayANCOVAreportedaboveasaregressionanalysis.Itisnowwellunderstoodthatanappropriatelyspecifiedregressionmodelcanproduceparameterestimatesidenticaltothoseofastandardanalysisofvariance(J.Cohen,Cohen,West,&Aiken,2003).ThusonecanuseregressiontoimplementaparticularanalysisofvarianceorANCOVAcon-trastbyusingappropriatelycodeddummyvariablesandcontrolcovariates.Forexample,toimplementthevisiblesupportcontrast,weconstructedasetoffourdummyvariables.FirstweconstructedaVisibleAdummyvariable,inwhichparticipantsintheVisibleAconditionreceivedascoreof1andallotherparticipantsre-ceivedascoreof0.WeconstructedsimilarlycodeddummiesfortheVisibleB,InvisibleA,andInvisibleBconditions,andweleftthenosupportconditionasanomittedcategory.Inaregressionmodelwiththissetofdummyvariables(andthecontrolvariablesdiscussedearlier),theregressioncoefficientfortheVisibleAdummyvariablewasanadjustedmeandifferenceindistresschangebetweenitandthenosupportcategory.OncetheoriginalANCOVAanalysiswasimplementedusingaregressionapproach,wethenincludedappropriatemediatorsinthemodelandpro-ceededwithastandardmediationanalysis.

470

BOLGERANDAMAREL

Thus,Step1oftheanalysisinvolvedestimatingaregressionmodelwiththefourdummyvariablesandthethreecovariatesasindependentvariablesandchangeindistressasthedependentvariable;thisreproducedtheestimatesforaparticularcontrast,thatis,VisibleAversusnosupport.Step2involvedtworegres-sions,oneforeachmediator,inwhichthedummyvariablesandcovariateswereagaintreatedasasetofindependentvariablesandeachmediatorwastreatedasadependentvariable.Thethirdandfinalstepinvolvedincludingthemediatorsasadditionalindepen-dentvariablesinthemodelestimatedinStep1(seeKennyetal.,1998,foraworkedexampleinvolvingmultiplemediators).

Visiblesupportcontrast.Asalreadynoted,participantsintheVisibleAconditionshoweda1.09unitsgreaterincreaseindistressthanparticipantsinthenosupportcondition.Inthelanguageofmediationanalysis,thisisthetotaleffecttobeexplained(obtainedinStep1ofamediationanalysis),anditislistedinthefirstrow,finalcolumnofTable5.Towhatextentcanthisdifferencebeexplainedbythemediatingvariables,particularlyreflectedap-praisalofinefficacy?ThesecondcolumnofTable5,labeled“Pathto”showsthelinkbetweentheVisibleAversusnosupportcontrastandreflectedappraisalofinefficacy(Step2ofthemedi-ationanalysis).ItshowsthatparticipantsintheVisibleAconditionwereapproximately2unitshigherininefficacyappraisal(ona0–10scale)thanthoseinthenosupportcondition(Mdiff.?2.15,SE?0.43),t(142)?4.91,p?.000,CI?1.28,3.01.

ThethirdcolumninTable5,labeled“Pathfrom,”showsresultsfromStep3ofthemediationanalysis,thestepthattracesthelinkbetweenreflectedappraisalofinefficacyandchangeindistress,whileholdingtheothermediator(upwardsocialcomparison)andtheStep1IVsconstant.Itshowsthatparticipantswhowere1unithigherininefficacyappraisalwereonaverage0.23unitshigherinincreasesindistress(SE?0.06),t(140)?3.82,p?.0002,CI?0.11,0.34.

Theproductofthesetwolinks,2.14?0.23?0.49(showninthefourthcolumn,labeled“Mediated”),istheportionoftheoriginalVisibleAversusnosupportcontrastthatismediatedbyinefficacyappraisal.UsingtheShroutandBolger(2002)bootstrapapproachtoassessingsamplingvariabilityofmediatedeffects,wefoundthiseffecttobestatisticallysignificantandtohavealowerboundCIthatwasconsiderablygreaterthanzero(CIb?0.19,0.91,p?.003,whereCIbreferstothebootstrapCI).Notethatbecausethebootstrapapproachdidnotassumeaparticularsam-plingdistributionfortheindirecteffect,therewasnoconventionaldistribution-basedteststatistic(e.g.,t,z)toreport.Weusedthisbootstrapapproachbecauseitprovidesamoreaccurateandsta-tisticallypowerfultestofthesignificanceofamediatedeffectthantheusualSobeltest(Sobel,1982,1986).DetailsonthebootstrapapproachtogetherwithworkedexamplescanbefoundinShroutandBolger(2002).

Wecanseefromtheequivalentcolumnsforupwardsocialcomparisonthatitwasnotanappreciablemediatorofthecontrast.Althoughengaginginupwardsocialcomparisonwasassociatedwithincreaseddistressirrespectiveofcondition(coefficient?0.31,SE?0.09),t(140)?3.59,p?.0005,CI?0.14,0.48,participantsinthetwoconditionsdidnotdiffersubstantiallyintheiruseofupwardsocialcomparison.Theestimateofthemedi-atedeffectis0.11andisnotstatisticallysignificant(CIb??0.05,0.37,p?.144).

Takentogether,inefficacyappraisalandupwardsocialcompar-isonaccountedfor0.60units,orjustoverhalfofthecontrastmean

%0

00

g0000n%1111isu59)3)ed(l)n535)

irat.ae*

teot

97*

000..9bPTnuo019?10*

654.,1o.1,.,.30567.0,ehm469rt.?.?02.0.eiAWw(0?1?1(0(s(lneovsein

ro%

5

5

1

lai412etcpisdnmoea)))copt458)

ifCmait

1541ioden...01504ndcu.go5,130*

,1iremsadm..04612,.8,13dwhUnA.0?0805..700?.2.ntpa??0?0a(UP(((sladrvn%

5

r5seas9

5t8e7niyceac))cd95)

nie)etf037dfat

.1.iei*

2n.fndeu01*

0*

.38070nI618?4?0,omo....0,0,0,7cfMo243,A.s.?73.?109tl01.?0ca(?0??es(f((fiaerdp))))

ep725t3101d

aAi.e1.7..2drdt100200.0aeorei.,0,1,0d05.1.7.,mretce0030301rr

..2eeM0??..0ogl??00??Fnifeep.((((Ro0dt1nuh))))

orotgnousm

880ootoir*

4488.*

.4ra100*

.*

4.rfmeh311010h,,ou.3,3,rTmp043...tfda104104104...1soP000.dertc(((0(engaedrniaawc))))

roriw479f9319hfpo

cheU5.5icot303.00.0.0haCh.,2,4004..,0,wet00208.8afnn.0?8.5P0?90..oihoi??0??0htitr

((((ciawsoesota,epi))simd44)

ece)rno13.19d

.oecM*

ct99*

0*

00e.t.ssie4067?53?70assDi0,d..0,,.,.sny

e9080008eohcraM1272.tct.?.?.?c01snaiii(Pf?0??0(dlf((laeac:innierigfef))))

nom

4dmal*

33444onuha..*

3.*

3.ranCsf30*

3030302ltia,2,2,..aihsrth012,.110101.1tgpaiis..101pP00..nleiSra((00((tn.de)siee2Dt))c1)

w0e)t0nl1505.7.e2ofo

*

*

*

5.b,)

erst40.82600133?5?13eeseR,..ctsth2,83,.5,.7nglceea2211eohP.rf.?.?1414.?01eBfEtfn(?2??fe(i&lr((dtaaeutnPhotretnrtshmiSiroioesgereelpypapcpa:unspva(x:ucts:rt

tsirhsEsrfooyeaoofcA

ctsodfnrpneApnpatc.ssoInpinou.s.u.ssvehtreneCsvtsvifnveftBscimoneelAelAieD.

ip5taebpBbienila0ibr.iieilitdfslceslibrs.niiest?eoVbeieisRbvisesInivPvtC.i.inooM1V2V.3n.I4INopb*Table5

EFFECTSOFSUPPORTVISIBILITY

471

differenceof1.09units,withinefficacyappraisalaloneaccountingfor45%ofthemeandifference.Theremainingportionofthecontrast,0.50units,isshownunderthelabel“Unmediated.”ThisestimatewasobtainedinStep3ofthemediationalanalysis.

Recipientinefficacycontrast.Wehavealreadyshownthatcomparedwiththenosupportcondition,thestandardVisibleAconditionwasemotionallydetrimentalandthatalmosthalfofthisdifferencewasattributabletorecipientsreportinggreaterreflectedappraisalsofinefficacy.GiventhattheVisibleBcondition,inwhichrecipientinefficacywasnotcommunicated,resultedinarelativereductionindistresscomparedwithVisibleA(?0.99units),canthisrelativereductionbeaccountedforbytherecipientreportinglessinefficacyappraisal?Theanswerisaveryclearyes.RecipientsintheVisibleBconditionreportedanaverageof3.38unitslessinefficacyappraisalthanrecipientsintheVisibleAcondition.Giventhatforeachadditionalunitofinefficacyap-praisal,distresschangeincreasedby0.23units,thisaccountsforadistressdifferenceof?3.38?0.23??0.76units(CI?0.34,p?.004),whichisapproximately75%ofb?the?1.28,totaldifferencebetweentheconditions.Notethatupwardsocialcom-parisonappearstoplaynoroleinaccountingforthiscontrast.Invisiblesupportcontrast.Themediationalanalysisofthiscontrastrevealedthatalthoughwehadhypothesizedthatreducedupwardcomparisonwouldhelpaccountforthebenefitsofinvis-iblesupport,thiswasnotthecase.AsTable5shows,participantsintheInvisibleAconditionwerelesslikelytoengageinupwardsocialcomparisonthanthoseinthenosupportcondition,butthemeandifferencewasrelativelysmallandnotsignificant(coeffi-cient??.40),t(142)?1.34,p?.182,CI??0.98,0.19.Thisfailuretofindmediationbyupwardsocialcomparisonissome-whatinconsistentwiththeexperimentalresultsshownearlier.Instead,reflectedappraisalofinefficacyemergedasakeymediator.ParticipantsintheInvisibleAconditionwere1.56unitslesslikelytoengageininefficacyappraisalthanthoseinthenosupportcondition,t(142)?3.59,p?.0005,CI??2.41,?0.70,andgiventhata1-unitlowerinefficacyappraisalwasassociatedwith0.23unitslowerdistress,theindirecteffectis?1.56?0.23??.35distressunits(CIb??0.70,?0.14,p?.002).Peerinefficacycontrast.Inthisfinalmediationanalysis,weagainfoundevidenceofinconsistencybetweentheresultsofthetwoanalyticstrategies:Althoughremovingthecommunicationofpeerinefficacywasassociatedwithincreaseddistress(Mdiff.?0.75),thiseffectcouldnotbeexplainedbyrecipientsreportsofengaginginlessupwardcomparison.Therewasnodifferenceintheaverageuseofupwardsocialcomparisonbetweenthetwoconditions(Mdiff.?0.003),t(142)?0.00,p?.992.

Itissurprisingthatupwardsocialcomparisondidnotmediatetheeffectoftheinvisiblesupportconditions.Havingseenthatupwardsocialcomparisonpredictedincreasesindistressindepen-dentlyofcondition,wedidnotseetheproblemasduetounreli-abilityofmeasurement.Itispossible,however,thatthetwo-itemmeasurethatfocusedonlyonrelativeknowledgeandnervousnessdidnotcoverasufficientrangeofsocialcomparisondimensions.Furthermore,acrossallconditions,themeanreporteduseofup-wardsocialcomparisonwaslowerthanweanticipated,3.71ona0–10scale,midwaybetween“alittle”and“moderately.”Giventhattheconfederate(a)presentedherselfasapeerfacingasimilarevaluativesituation,(b)offeredadviceintwoofthefivecondi-tions,and(c)expressedconcernaboutherownperformanceinonlyoneofthefiveconditions,onemightreasonablyhaveex-

pectedhertoevokeahigherlevelofupwardcomparisonoverall.Itseemsthatfurtherevidenceisnecessarybeforeanyfirmcon-clusionscanbedrawnregardingsocialcomparisonasamediator.Summary.TheaimofStudy3wastousebothexperimentalandstatisticalcontroltechniquestoinvestigatepotentialmediatorsofvisibilityandinvisibilityeffects.Threenoteworthypatternsemerged.First,theexperimentalanalysis(a)replicatedthedetri-mentaleffectofvisiblesupportfoundinStudy2and(b)showedthatremovingtheinefficacycommunicationundidtheeffect.Thestatisticalmediationanalysisconfirmedthisinterpretation.Sec-ond,theexperimentalanalysisreplicatedthebeneficialeffectofinvisiblesupportfoundinStudy2,andremovingthecommuni-cationoftheprovider’sinefficacyappearedtoeliminatethiseffect.However,themediationalanalysisdidnotshowthatareductioninupwardsocialcomparisonaccountedforthiseffect.Rather,itrevealedthatreducedappraisalsofinefficacypartlyaccountedforit.Takentogether,theanalysesindicatedthecentralmediationalroleofreflectedappraisalsofinefficacyinexplainingboththedeleteriouseffectofvisibilityandthebeneficialeffectofinvisi-bility.Finally,althoughneithersupportvisibilityorinvisibilitynorsupportcontentperserelatedtostressorreactivity,theconstrainednatureofthesecontrastslimittheirinformativeness.

GeneralDiscussion

Ithasbeenmorethan3decadessincetheroleofsocialrela-tionshipsinpromotinghealthandpsychologicalfunctioningemergedasamajortopicofresearch(Stroebe&Stroebe,1996).Althoughtheepidemiologicalevidenceforthebenefitsofsocialrelationshipsisnowconsideredverystrong(see,e.g.,theclassicreviewbyHouse,Landis,&Umberson,1988),thesocialpsycho-logicalprocessesthatmediatetheseeffectsremainunclear.Inparticular,ithasprovendifficulttoshowthatsupportivesocialinteractionsplayabeneficialrole.Toexplainthisinconsistency,Bolgeretal.(2000)suggestedthatsupportrecipientsmaynotbeabletogiveaccurateaccountsofthesupporttheyreceiveandthataconsiderablenumberofsupportiveinteractionsoccur“undertheradar”andarenotinterpretedassupport.

Inthecurrentarticle,wecontinuedthislineofresearchandreportedtheresultsofthreeexperimentsdesignedtoinvestigatetheeffectivenessofsupportvisibilityinpromotingadjustmenttoasignificantstressor.ThepriorfieldresearchbyBolgeretal.(2000)andShroutetal.(2006)foundevidencesuggestingthatinvisiblesupport,thatis,interactionscodedbytheproviderassupportbutnotbytherecipient,wereeffectiveinpromotingadjustment,whereasvisiblesupportleftrecipientsatbestnobetteroffthaniftheyhadreceivednosupport.Broadlyspeaking,theresultsoftheseexperimentsservedtoconfirmthefindingsoftheearlierfieldresearch.Acrossthethreeexperiments,supportivebehaviorsbyconfederatepeersthatwereaccomplishedwithouttherecipients’awarenesswerethemosteffectiveinloweringemotionalreactivitytoasignificantstressor.Visiblesupport,bycontrast,appearedtobedetrimentaltoadjustmentor,atbest,ineffective.

ExplanatoryanalysesconductedinExperiment3demonstratedthecrucialmediationalroleoftherecipients’appraisalthatthesupportivepeerviewedthemasinefficacious.Thisreflectedap-praisalwasimportantinexplainingboththebenefitsofinvisiblesupportandthecostsofvisiblesupport.Supportattemptsthatavoidedevokingthisappraisalinrecipientsweremorelikelytobebeneficialthanthosethatdidnot;supportattemptsthatevokedthis

472

BOLGERANDAMAREL

appraisalweremorelikelytobedetrimentalthanthosethatdidnot.Thus,itappearsthatinvisibilityperseisnottheessenceofwhatmakesinvisiblesupporteffective;rather,itis(atleastinpart)avoidingthecommunicationthatthesupportrecipientisineffica-cious.

Itisimportanttoconsiderwhethertheseresults—thedetrimen-taleffectsofvisiblesupportinparticular—areduetothevisiblesupportbehaviorsbeingviewedasinappropriateorinsultingbyparticipants.Itiswellknownthatnaturallyoccurringsupportattemptsmaybemiscarriedinsuchways(Coyneetal.,1988;Lehman,Ellard,&Wortman,1986;Lehman&Hemphill,1990),andmoregenerally,evidenceisaccumulatingthatforsupportiveactstobeeffectivetheymustbetailoredtotheneedsoftherecipient(Cutrona&Cole,2000;Cutrona&Russell,1990).Fur-thermore,researchhasshownthatnegativesocialinteractionsarecommoninmostinterpersonalrelationships(Rook,1984,1990a,1998;Rook&Pietromonaco,1987).Ourmanipulationchecksandrecipientratingsofprovidersupportiveness,however,donotsus-tainthisinterpretation.Itappearsthatrecipientsregardedtheprovider’sbehaviorsaswellintentionedandhelpful.