网络结构和信息以及行为方式的传播

发表在美国《科学杂志》上的文章《The Spread of Behavior in an Online Social Network Experiment》,是美国麻省理工学院的经济社会学家 Damon Centola所撰写的一篇研究报告,研究的核心是两种社会网络结构——小世界网络和规则网络中行为的传播效率和效果。Damon Centola的研究结果对市场营销有重要的启发意义。

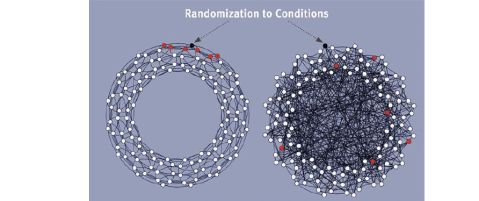

文章在开篇的时候,首先指出网络结构影响传播效率的两种假设。规则网络结构(下图左)和小世界网络(下图右)是两种常见的社会网络结构。两种网络结构各自具有鲜明的特

点,小世界网络由于有长程捷径的存在,具有小的平均距离,但是它的聚类系数很小;而规则网络有很高的聚类系数,每个节点的连接节点之间相互连接的概率很高,但是它没有长程捷径,所以平均距离很大关于不同网络结构中传播效率和效果存在两种假设。一种认为小世界网络结构的弱连接具有强作用,它的长程捷径使得信息可以在这一网络结构中更快和更大范围传播,而行为在社会网络中的传播和信息的传播具有相同的特点。另一种假设则认为信息和行为在传播方式上具有很大的差异,所以小世界网络在信息传播上的弱连接强作用照搬到行为的传播上是欠妥的,行为不依赖于接触,而是依赖于养成,需要多次的社会强化,在规则型网络结构中传播的效果更好。

为了验证两种假设孰对孰错,文章作者进行了一次实验。他邀请了1540名志愿者参加实验,并将这些参与者一对一地随机分配到两个基于互联网的健康社区,通过研究人员的安排,这两个社群中的参与者构成社会网络结构中的支点,每一个节点的度都是6,在研究人员的控制下,两个社群一个是具有小世界特性的随机网络,另一个是高聚类的规则网络。研究人员首先在这两个网络中选择了一个focal node(红点)作为起点,向与这两个点相连的6个红点(邻居)发送一封邮件,邀请他们到某个指定的健康论坛注册。如果他们到这个论坛注册就表示他们养成这种行为,那么系统再给他们的邻居发邮件邀请他们也去论坛注册(对于个人有可能被多次邀请),注册邀请会接着在养成行为的志愿者周围传播,让活动继续下去。整个实验的设计保证了参与者私下并不知道其他参与者的情报,实验所记录的参与者中行为传播的数据完全是网络结构传播效果的反应。根据实验记录的数据,

研究人员对在

两种不同网络下的行为的传播规律进行了分析。

通过这次研究,我们有如下发现:

1. 规则社会网络传播速度更快,传播范围更广。在给定的时间中,小世界网络的传播

速度是0.643×10^-4 节点每秒,而规则网络的传播速度则达到了2.820×10^-4节点每秒;至于行为传播范围,规则网络为53.77%,小世界网络只有38.27%。

2. 收到邮件的次数与对应的节点养成行为(愿意去健康论坛注册)的比例存在正相关,

从数据中明显可以看出收到次数越多就越有可能养成行为。

从文章作者的这次研究中,我们可以得出这样一个结论:行为方式与信息的传播方式是不同的。由于长程捷径的存在,信息在小世界网络中传播比较快,而行为方式的传播由于需要的多次强化这一特点使得它在高聚类规则网络中更具优势,比在小世界网络中传播得要更快更广。根据信息和行为的特点,代表了两种类型的网络传播,信息的扩散只需要简单地接触,行为的形成是非常复杂的,需要多次的强化、需要重复的刺激学习和养成,它的传播不属于接触传播,所以像高聚类网络具有冗余连接结构,适合于形成行为的多次强化作用,就有利于行为的形成、传播和巩固。

实验结论对于市场营销工作有很大的启迪。我们在营销我们的产品和服务的时候,我们会倾向于向消费者传递的内容可以分为两块儿,一个是关于我们提供的产品和服务的信息,诸如我们提供什么产品,产品具有什么样的顾客价值,具备哪些品质和特性,价格怎么样,竞争优势是什么;还有一个就是消费理念的表达,这是在努力向顾客灌输一些行为方式,养成使用自己推荐的产品和服务的习惯,比如淘宝。关于规则网络结构和小世界网络结构信息和行为扩散的研究告诉我们,信息和行为适用的网络结构是不一样的。所以在产品营销中,如果我们的目的是让大家知道我们的产品,我们应该使用小世界网络;相反如果我们关注的焦点是在让消费者养成特定的消费行为,那么我们采取规则网络往往可以事半功倍。

不过这个实验还有继续深入的空间,我认为实验中选择在一家健康网站上注册作为研究的传播行为可能代表性还有所欠缺,也就是说,会不会存在刺激强化得越多越抵制的行为。另外在信息的传播上小世界网络结构并不是占据着绝对的优势,我们都知道三人成虎、众口铄金的说法,信息的传播不仅要重视效率,还要要重视效果,多次的强化可以提高信息的可信度。这样的信息会不会对产品营销更有价值?这都需要营销人员具体斟酌要传播的信息本身的情况。

参考资料:《The Spread of Behavior in an Online Social Network Experiment》, Damon Centola

《SCIENCE》 20xx年9月3日329期。

《行为在高聚类网络中传播更快》,陆君安。

第二篇:Alone in the Crowd The Structure and Spread of Loneliness in a Large Social Network

AloneintheCrowd:TheStructureandSpreadofLonelinessina

LargeSocialNetwork

UniversityofChicago

JohnT.Cacioppo

UniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego

JamesH.Fowler

NicholasA.Christakis

HarvardUniversity

Thediscrepancybetweenanindividual’slonelinessandthenumberofconnectionsinasocialnetworkiswelldocumented,yetlittleisknownabouttheplacementoflonelinesswithin,orthespreadoflonelinessthrough,socialnetworks.Theauthorsusenetworklinkagedatafromthepopulation-basedFraminghamHeartStudytotracethetopographyoflonelinessinpeople’ssocialnetworksandthepaththroughwhichlonelinessspreadsthroughthesenetworks.Resultsindicatedthatlonelinessoccursinclusters,extendsupto3degreesofseparation,isdisproportionatelyrepresentedattheperipheryofsocialnetworks,andspreadsthroughacontagiousprocess.Thespreadoflonelinesswasfoundtobestrongerthanthespreadofperceivedsocialconnections,strongerforfriendsthanfamilymembers,andstrongerforwomenthanformen.Theresultsadvanceunderstandingofthebroadsocialforcesthatdrivelonelinessandsuggestthateffortstoreducelonelinessinsocietymaybenefitbyaggressivelytargetingthepeopleintheperipherytohelprepairtheirsocialnetworksandtocreateaprotectivebarrieragainstlonelinessthatcankeepthewholenetworkfromunraveling.

Keywords:loneliness,socialnetwork,socialisolation,contagion,longitudinalstudy

Humansocialisolationisrecognizedasaproblemofvastimportance.(Harlow,Dodsworth,&Harlow,1965,p.90)

Socialspeciesdonotfarewellwhenforcedtolivesolitarylives.Socialisolationdecreasesthelifespanofthefruitfly,Drosophiliamelanogaster(Ruan&Wu,2008);promotesthedevelopmentofobesityandType2diabetesinmice(Nonogaki,Nozue,&Oka,2007);delaysthepositiveeffectsofrunningonadultneurogenesisinrats(Stranahan,Khalil,&Gould,2006);increasestheactivationofthesympatho-adrenomedullaryresponsetoanacuteimmobili-zationorcoldstressorinrats(Dronjak,Gavrilovic,Filipovic,&Radojcic,2004);decreasestheexpressionofgenesregulatingglucocorticoidresponseinthefrontalcortexofpiglets(Poletto,Steibel,Siegford,&Zanella,2006);decreasesopenfieldactivity,increasesbasalcortisolconcentrations,anddecreaseslymphocyteproliferationtomitogensinpigs(Kanitz,Tuchscherer,Puppe,

JohnT.Cacioppo,DepartmentofPsychology,UniversityofChicago;JamesH.Fowler,DepartmentofPoliticalScience,UniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego;NicholasA.Christakis,DepartmentofHealthCarePolicy,Har-vardMedicalSchoolandDepartmentofSociology,HarvardUniversity.TheresearchwassupportedbyNationalInstituteonAgingGrantsR01AG034052-01(toJohnT.Cacioppo),P01AG031093,andR01AG24448(toNicholasA.Christakis).

CorrespondenceconcerningthisarticleshouldbeaddressedtoJohnT.Cacioppo,DepartmentofPsychology,UniversityofChicago,Chicago,IL,60637.E-mail:Cacioppo@uchicago.edu

Tuchscherer,&Stabenow,2004);increasesthe24-hrurinarycatecholamineslevelsandevidenceofoxidativestressintheaorticarchoftheWatanabeheritablehyperlipidemicrabbit(Nationetal.,2008);increasesthemorningrisesincortisolinsquirrelmonkeys(Lyons,Ha,&Levine,1995);andprofoundlydisruptspsychosex-ualdevelopmentinrhesusmonkeys(Harlowetal.,1965).

Humans,borntothelongestperiodofabjectdependencyofanyspeciesanddependentonconspecificsacrossthelifespantosur-viveandprosper,donotfarewell,either,whethertheyarelivingsolitarylivesorwhethertheysimplyperceivethattheyliveinisolation.Theaveragepersonspendsabout80%ofwakinghoursinthecompanyofothers,andthetimewithothersispreferredtothetimespentalone(Emler,1994;Kahneman,Krueger,Schkade,Schwarz,&Stone,2004).Socialisolation,incontrast,isassoci-atednotonlywithlowersubjectivewell-being(Berscheid,1985;Burt,1986;Myers&Diener,1995)butalsowithbroad-basedmorbidityandmortality(House,Landis,&Umberson,1988).Humansareanirrepressiblymeaning-makingspecies,andalargeliteraturehasdevelopedshowingthatperceivedsocialiso-lation(i.e.,loneliness)innormalsamplesisamoreimportantpredictorofavarietyofadversehealthoutcomesthanisobjectivesocialisolation(e.g.,(Coleetal.,2007;Hawkley,Masi,Berry,&Cacioppo,2006;Penninxetal.,1997;Seeman,2000;Sugisawa,Liang,&Liu,1994).Inanillustrativestudy,Caspi,Harrington,Moffitt,Milne,&Poulton(2006)foundthatlonelinessinadoles-cenceandyoungadulthoodpredictedhowmanycardiovascular

JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,2009,Vol.97,No.6,977–991

?2009AmericanPsychologicalAssociation0022-3514/09/$12.00DOI:10.1037/a0016076

977

978

CACIOPPO,FOWLER,ANDCHRISTAKIS

riskfactors(e.g.,bodymassindex,waistcircumference,bloodpressure,cholesterol)wereelevatedinyoungadulthoodandthatthenumberofdevelopmentaloccasions(i.e.,childhood,adoles-cence,youngadulthood)atwhichparticipantswerelonelypre-dictedthenumberofelevatedriskfactorsinyoungadulthood.LonelinesshasalsobeenassociatedwiththeprogressionofAlzheimer’sdisease(Wilsonetal.,2007),obesity(Lauder,Mum-mery,Jones,&Caperchione,2006),increasedvascularresistance(Cacioppo,Hawkley,Crawford,etal.,2002),elevatedbloodpres-sure(Cacioppo,Hawkley,Crawford,etal.,2002;Hawkleyetal.,2006),increasedhypothalamicpituitaryadrenocorticalactivity(Adam,Hawkley,Kudielka,&Cacioppo,2006;Steptoe,Owen,Kunz-Ebrecht,&Brydon,2004),lesssalubrioussleep(Cacioppo,Hawkley,Berntson,etal.,2002;Pressmanetal.,2005),dimin-ishedimmunity(Kiecolt-Glaseretal.,1984;Pressmanetal.,2005),reductioninindependentliving(Russell,Cutrona,delaMora,&Wallace,1997;Tilvis,Pitkala,Jolkkonen,&Strandberg,2000),alcoholism(Akerlind&Hornquist,1992),depressivesymptomatology(Cacioppoetal.,2006;Heikkinen&Kauppinen,2004),suicidalideationandbehavior(Rudatsikira,Muula,Siziya,&Twa-Twa,2007),andmortalityinolderadults(Penninxetal.,1997;Seeman,2000).Lonelinesshasevenbeenassociatedwithgeneexpression:specifically,theunder-expressionofgenesbear-inganti-inflammatoryglucocorticoidresponseelementsandover-expressionofgenesbearingresponseelementsforproinflamma-toryNF-?B/Reltranscriptionfactors(Coleetal.,2007).

Adoptionandtwinstudiesindicatethatlonelinesshasasizableheritablecomponentinchildren(Bartels,Cacioppo,Hudziak,&Boomsma,2008;McGuire&Clifford,2000)andinadults(Boomsma,Cacioppo,Muthen,Asparouhov,&Clark,2007;Boomsma,Cacioppo,Slagboom,&Posthuma,2006;Boomsma,Willemsen,Dolan,Hawkley,&Cacioppo,2005).Socialfactorshaveasubstantialimpactonloneliness,aswell,however.Forinstance,freshmenwholeavefamilyandfriendsbehindoftenfeelincreasedsocialisolationwhentheyarriveatcollege,eventhoughtheyaresurroundedbylargenumbersofotheryoungadults(e.g.,Cutrona,1982;Russell,Peplau,&Cutrona,1980).Lowerlevelsoflonelinessareassociatedwithmarriage(Hawkley,Browne,&Cacioppo,2005;Pinquart&Sorenson,2003),highereducation(Savikko,Routasalo,Tilvis,Strandberg,&Pitkala,2005),andhigherincome(Andersson,1998;Savikkoetal.,2005),whereashigherlevelsoflonelinessareassociatedwithlivingalone(Routasalo,Savikko,Tilvis,Strandberg,&Pitkala,2006),infre-quentcontactwithfriendsandfamily(Bondevik&Skogstad,1998;Hawkleyetal.,2005;Mullins&Dugan,1990),dissatisfac-tionwithlivingcircumstances(Hector-Taylor&Adams,1996),physicalhealthsymptoms,chronicworkand/orsocialstress(Hawkleyetal.,2008),smallsocialnetwork(Hawkleyetal.,2005;Mullins&Dugan,1990),lackofaspousalconfidant(Hawkleyetal.,2008),maritalorfamilyconflict(Jones,1992;Segrin,1999),poorqualitysocialrelationships(Hawkleyetal.,2008;Mullins&Dugan,1990;Routasaloetal.,2006),anddivorceandwidowhood(Dugan&Kivett,1994;Dykstra&deJongGierveld,1999;Holmen,Ericsson,Andersson,&Winblad,1992;Samuelsson,Andersson,&Hagberg,1998).

Thediscrepancybetweenanindividual’ssubjectivereportoflonelinessandthereportedorobservednumberofconnectionsintheirsocialnetworkiswelldocumented(e.g.,seeBerscheid&Reis,1998),butfewdetailsareknownabouttheplacementoflonelinesswithinorthespreadoflonelinessthroughasocialnetwork.Theassociationbetweenthelonelinessofindividualsconnectedtoeachother,andtheirclusteringwithinthenetwork,couldbeattributedtoatleastthreesocialpsychologicalprocesses.First,theinductionhypothesispositsthatthelonelinessinonepersoncontributestoorcausesthelonelinessinothers.Theemo-tional,cognitive,andbehavioralconsequencesoflonelinessmaycontributetotheinductionofloneliness.Forinstance,emotionalcontagionreferstothetendencyforthefacialexpressions,vocaliza-tions,postures,andmovementsofinteractingindividualstoleadtoaconvergenceoftheiremotions(Hatfield,Cacioppo,&Rapson,1994).Whenpeoplefeellonely,theytendtobeshyer,moreanxious,morehostile,moresociallyawkward,andlowerinself-esteem(e.g.,Ber-scheid&Reis,1998;Cacioppoetal.,2006).Emotionalcontagioncouldthereforecontributetothespreadoflonelinesstothosewithwhomtheyinteract.Cognitively,lonelinesscanaffectandbeaffectedbywhatoneperceivesanddesiresintheirsocialrelationships(Peplau&Perlman,1982;Rook,1984;Wheeler,Reis,&Nezlek,1983).Totheextentthatinteractionswithothersinanindividual’ssocialnet-workinfluenceaperson’sidealorperceivedinterpersonalrelation-ship,thatperson’slonelinessshouldbeinfluenced.Behaviorally,whenpeoplefeellonely,theytendtoacttowardothersinalesstrustingandmorehostilefashion(e.g.,Rotenberg,1994;cf.Berscheid&Reis,1998;Cacioppo&Patrick,2008).Thesebehaviors,inturn,maylowerthesatisfactionofotherswiththerelationshiporleadtoaweakeningorlossoftherelationshipandaconsequentinductionoflonelinessinothers.

Second,thehomophilyhypothesispositsthatlonelyornon-lonelyindividualschooseoneanotherasfriendsandbecomeconnected(i.e.,thetendencyofliketoattractlike;McPherson,Smith-Lovin,&Cook,2001).Byrne’s(1971)lawofattractionspecifiesthatthereisadirectlinearrelationshipbetweeninterper-sonalattractionandtheproportionofsimilarattitudes.Theasso-ciationbetweensimilarityandattractionisnotlimitedtoattitudes,andthecharacteristicsonwhichsimilarityoperatesmovefromobviouscharacteristics(e.g.,physicalattractiveness)tolessobvi-ousones(socialperceptions)asrelationshipsdevelopanddeepen(e.g.,Neimeyer&Mitchell,1988).Althoughfeelingsoflonelinesscanbetransient,stableindividualdifferencesinlonelinessmayhavesufficientlybroadeffectsonsocialcognition,emotion,andbehaviortoproducesimilarity-basedsocialsorting.

Finally,thesharedenvironmenthypothesispositsthatcon-nectedindividualsjointlyexperiencecontemporaneousexposuresthatcontributetoloneliness.Loneliness,forinstance,tendstobeelevatedinmatriculatingstudents,becauseformany,theirarrivalatcollegeisassociatedwitharuptureofnormaltieswiththeirfamilyandfriends(Cutrona,1982).Peoplewhointeractwithinasocialnetworkmayalsobemorelikelytobeexposedtothesamesocialchallengesandupheavals(e.g.,coresidenceinadangerousneighborhood,jobloss,retirement).

Todistinguishamongthesehypothesesrequiresrepeatedmea-suresofloneliness,longitudinalinformationaboutnetworkties,andinformationaboutthenatureordirectionoftheties(e.g.,whonominatedwhomasafriend;Carrington,Scott,&Wasserman,2005;Fowler&Christakis,2008b).Withtherecentapplicationofinnovativeresearchmethodstonetworklinkagedatafromthepopulation-basedFraminghamHeartStudy(FHS),thesedataarenowavailableandhavebeenusedtotracethedistinctivepathsthroughwhichobesity(Christakis&Fowler,2007),smoking

STRUCTUREANDSPREADOFLONELINESS

979

(Christakis&Fowler,2008),andhappiness(Fowler&Christakis,2008a)spreadthroughpeople’ssocialnetworks.Wesoughtheretousethesemethodsanddatatodeterminetheroleofsocialnetworkprocessesinloneliness,withanemphasisondeterminingthetopog-raphyoflonelinessinpeople’ssocialnetworks,theinterdependenceofsubjectiveexperiencesoflonelinessandtheobservedpositioninsocialnetworks,thepaththroughwhichlonelinessspreadsthroughthesenetworks,andfactorsthatmodulateitsspread.

Method

AssemblingtheFHSSocialNetworkDataset

TheFHSisapopulation-based,longitudinal,observationalco-hortstudythatwasinitiatedin1948toprospectivelyinvestigateriskfactorsforcardiovasculardisease.Sincethen,ithascometobecomposedoffourseparatebutrelatedcohortpopulations:(1)the“OriginalCohort,”enrolledin1948(n?5,209);(2)the“OffspringCohort”(thechildrenoftheOriginalCohortandspousesofthechildren),enrolledin1971(n?5,124);(3)the“OmniCohort,”enrolledin1994(n?508);and(4)the“Gener-ation3Cohort”(thegrandchildrenoftheOriginalCohort),en-rolledbeginningin2002(n?4,095).TheOriginalCohortactuallycapturedthemajorityoftheadultresidentsofFraminghamin1948,andtherewaslittlerefusaltoparticipate.TheOffspringCohortincludedoffspringoftheOriginalCohortandtheirspousesin1971.Thesupplementary,multiethnicOmniCohortwasiniti-atedtoreflecttheincreaseddiversityinFraminghamsincetheinceptionoftheOriginalCohort.FortheGeneration3Cohort,OffspringCohortparticipantswereaskedtoidentifyalltheirchildrenandthechildren’sspouses,and4,095participantswereenrolledbeginningin2002.Publishedreportsprovidedetailsaboutsamplecompositionandstudydesignforallthesecohorts(Cupples&D’Agnostino,1988;Kannel,Feinleib,McNamara,Garrison,&Castelli,1979;Quanetal.,1997).

Continuoussurveillanceandserialexaminationsoftheseco-hortsprovidelongitudinaldata.Alloftheparticipantsareperson-allyexaminedbyFHSphysiciansandnurses(or,forthesmallminorityforwhomthisisnotpossible,evaluatedbytelephone)andwatchedcontinuouslyforoutcomes.TheOffspringstudyhascollectedinformationonhealtheventsandriskfactorsroughlyevery4years.TheOriginalCohorthasdataavailableforroughlyevery2years.ItisimportanttonotethatevenparticipantswhomigrateoutofthetownofFramingham(topointsthroughouttheUnitedStates)remaininthestudyand,remarkably,comebackeveryfewyearstobeexaminedandtocompletesurveyforms;thatis,thereisnonecessarylosstofollow-upbecauseofout-migrationinthisdataset,andverylittlelosstofollow-upforanyreason(e.g.,only10casesoutof5,124intheOffspringCohorthavebeenlost).Forthepurposesoftheanalysesreportedhere,examwavesfortheOriginalCohortwerealignedwiththoseoftheOffspringCohort,sothatallparticipantsinthesocialnetworkweretreatedashavingbeenexaminedatjustsevenwaves(inthesametimewindowsastheOffspring,asnotedinTable1).

TheOffspringCohortisthekeycohortofinteresthere,anditisoursourceofthefocalparticipants(FPs)inournetwork.How-ever,individualstowhomtheseFPsarelinked—inanyofthefourcohorts—arealsoincludedinthenetwork.Theselinkedindivid-ualsaretermedlinkedparticipants(LPs).Thatis,whereasFPs

Table1

SurveyWavesandSampleSizesoftheFraminghamOffspringCohort(NetworkFocalParticipants)

Surveywave/TimeNo.No.aliveNo.%ofadultsphysicalexamperiodaliveand18?examinedparticipatingExam11971–19755,1244,9145,124100.0Exam21979–19825,0535,0373,86376.7Exam31984–19874,9744,9733,87377.9Exam41987–19904,9034,9034,01982.0Exam51991–19954,7934,7933,79979.3Exam61996–19984,6304,6303,53276.3Exam7

1998–2001

4,486

4,486

3,539

78.9

comeonlyfromtheOffspringCohort,LPsaredrawnfromtheentiresetofFHScohorts(includingalsotheOffspringCohortitself).Hence,thetotalnumberofindividualsintheFHSsocialnetworkis12,067,becauseLPsidentifiedintheOriginal,Generation3,andOmniCohortsarealsoincluded,aslongastheywerealivein1971orlater.SpouseswholistadifferentaddressofresidencethantheFParetermednoncoresidentspouses.Therewere311FPswithnoncoresidentspousesinExam6and299inExam7.

Thephysical,laboratory,andsurveyexaminationsoftheFHSparticipantsprovideawidearrayofdata.Ateachevaluation,partic-ipantscompleteabatteryofquestionnaires(e.g.,theCenterforEpidemiologicalStudiesDepressionScale[CES–D;Radloff,1977]measureofdepressionandloneliness,asdescribedbelow),aphysician-administeredmedicalhistory(includingreviewofsymp-tomsandhospitalizations),aphysicalexaminationadministeredbyphysiciansonsiteattheFHSfacility,andalargevarietyoflabtests.Toascertainthenetworkties,wecomputerizedinformationfromarchived,handwrittendocumentsthathadnotpreviouslybeenusedforresearchpurposes,namely,theadministrativetrack-ingsheetsusedbytheFHSsince1971bypersonnelresponsibleforcallingparticipantstoarrangetheirperiodicexaminations.Thesesheetsrecordtheanswerswhenall5,124oftheFPswereaskedtocomprehensivelyidentifyrelatives,friends,neighbors(basedonaddress),coworkers(basedonplaceofemployment),andrelativeswhomightbeinapositiontoknowwheretheFPswouldbein2to4years.Thekeyfactherethatmakestheseadministrativerecordssovaluableforsocialnetworkresearchisthat,giventhecompactnatureoftheFraminghampopulationintheperiodfrom1971to2007,manyofthenominatedcontactswerethemselvesalsoparticipantsofoneoranotherFHScohort.WehaveusedthesetrackingsheetstodevelopnetworklinksforFHSOffspringparticipantstootherparticipantsinanyofthefourFHScohorts.Thus,forexample,itispossibletoknowwhichparticipantshavearelationship(e.g.,spouse,sibling,friend,co-worker,neighbor)withotherparticipants.Ofnote,eachlinkbe-tweentwopeoplemightbeidentifiedbyeitherpartyidentifyingtheother;thisobservationismostrelevanttothe“friend”link,aswecanmakethislinkeitherwhenAnominatesBasafriend,orwhenBnominatesA(and,asdiscussedbelow,thisdirectionalityismethodologicallyimportantandmightalsobesubstantivelyinteresting).PeopleinanyoftheFHScohortsmaymarryorbefriendorlivenexttoeachother.Finally,giventhehighqualityofaddressesintheFHSdata,thecompactnatureofFramingham,thewealthofinformationavailableabouteachparticipant’sresi-

980

CACIOPPO,FOWLER,ANDCHRISTAKIS

dentialhistory,andnewmappingtechnologies,wedeterminedwhoiswhoseneighbor,andwecomputeddistancesbetweenindividuals(Fitzpatrick&Modlin,1986).

ThemeasureoflonelinesswasderivedfromtheCES–Dadminis-teredbetween1983and2001attimescorrespondingtothefifth,sixth,andseventhexaminationsoftheOffspringCohort.Themedianyearofexaminationfortheseindividualswas1986forExam5,1996forExam6,and2000forExam7.Participantsareaskedhowoftenduringthepreviousweektheyexperiencedaparticularfeeling,withfourpossibleanswers:0–1days,1–2days,3–4days,and5–7days.Toconvertthesecategoriestodays,werecodedtheseresponsesatthecenterofeachrange(0.5,1.5,3.5,and6).FactoranalysesoftheitemsfromtheCES–DandtheUniversityofCalifornia,LosAngeleslonelinessscalesindicatethattheyrepresenttwoseparatefactors,andthe“Ifeltlonely”itemfromtheCES–Dscaleloadsonaseparatefactorfromthedepressionitems(Cacioppoetal.,2006).Theface-validnatureoftheitemalsosupportedtheuseofthe“HowoftenIfeltlonely”itemtogaugeloneliness.

Table2showssummarystatisticsforloneliness,networkvari-ables,andcontrolvariablesweusetostudythestatisticalrelation-shipbetweenfeelinglonelyandbeingalone.

StatisticalInformationandSensitivityAnalyses

Todistinguishamongtheinduction,homophily,andsharedenvironmenthypothesesrequiresrepeatedmeasuresofloneliness,longitudinalinformationaboutnetworkties,andinformationaboutthenatureordirectionoftheties(e.g.,whonominatedwhomasafriend;Carringtonetal.,2005;Fowler&Christakis,2008b).FortheanalysesinTable3,weaveragedacrosswavestodeterminethemeannumberofsocialcontactsforpeopleineachofthefourlonelinesscategories.FortheanalysesinTables4and5,weconsideredtheprospectiveeffectofLPs,socialnetworkvariables,andothercontrolvariablesonFP’sfutureloneliness.FortheanalysesinTables6–12,weconductedregressionsofFPloneli-nessasafunctionofFP’sage,gender,education,andlonelinessinthepriorexamandofthegenderandlonelinessofanLPinthecurrentandpriorexam.ThelaggedobservationsforWave7arefromWave6andthelaggedobservationsforWave6arefromWave5.InclusionofFPlonelinessatthepriorexameliminates

Table2

SummaryStatisticsfortheFraminghamOffspringCohort(NetworkFocalParticipants)

Variable

MSDMinMaxCurrentno.ofdaysperweekfeelinglonely

0.8530.9640.56Priorwaveno.ofdaysperweekfeelinglonely

0.9401.0860.56Currentno.offamilymembers2.8193.071023Priorwaveno.offamilymembers

3.0353.255026Currentno.ofclosefriends0.8970.89406Priorwaveno.ofclosefriends0.9510.91106Female

0.5490.49801Yearsofeducation13.5732.409217Age(years)63.787

11.848

29.667

101.278

Note.

Min?minimum;Max?maximum.

serialcorrelationintheerrorsandalsosubstantiallycontrolsforFP’sgeneticendowmentandanyintrinsic,stabletendencytobelonely.LP’slonelinessatthepriorexamhelpscontrolforhomoph-ily(Carringtonetal.,2005),whichhasbeenverifiedinMonteCarlosimulations(Fowler&Christakis,2008b).

ThekeycoefficientinthesemodelsthatmeasurestheeffectofinductionisonthevariableforLPcontemporaneousloneliness.Weusedgeneralizedestimatingequation(GEE)procedurestoaccountformultipleobservationsofthesameFPacrosswavesandacrossFP–LPpairings(Liang&Zeger,1986).Weassumedanindependentworkingcorrelationstructurefortheclusters(Schild-crout&Heagerty,2005).TheseanalysesunderlietheresultspresentedinFigure4.

TheGEEregressionmodelsinthetablesprovideparameteresti-matesthatareapproximatelyinterpretableaseffectsizes,indicatingthenumberofextradaysoflonelinessperweektheFPexperiencesgivenaone-unitincreaseintheindependentvariable.Meaneffectsizesand95%confidenceintervals(CIs)werecalculatedbysimulat-ingthefirstdifferenceinLPcontemporaneousloneliness(changingfrom0.5daysfeelinglonelyto1.5days)using1,000randomlydrawnsetsofestimatesfromthecoefficientcovariancematrixandassumingallothervariablesareheldattheirmeans(King,Tomz,&Wittenberg,2000).Wealsocheckedallresultsusinganorderedlogitspecifica-tion,andnoneofthesemodelschangedthesignificanceofanyreportedresult;wethereforedecidedtopresentthesimplerandmoreeasilyinterpretablelinearspecifications.

Theregressioncoefficientshavemostlytheexpectedeffects,suchthat,forexample,FP’spriorlonelinessisthestrongestpredictorforcurrentloneliness.Themodelsinthetablesincludeexamfixedeffects,which,combinedwithageatbaseline,accountfortheagingofthepopulation.Thesamplesizeisshownforeachmodel,reflectingthetotalnumberofallsuchties,withmultipleobservationsforeachtieifitwasobservedinmorethanoneexam,andallowingforthepossibilitythatagivenpersoncanhavemultipleties.Aspreviouslyindicated,repeatedobservationswerehandledwithGEEprocedures.

Weevaluatedthepossibilityofomittedvariablesorcontempo-raneouseventsexplainingtheassociationsbyexamininghowthetypeordirectionofthesocialrelationshipbetweenFPandLPaffectstheassociationbetweenFPandLP.IfunobservedfactorsdrivetheassociationbetweenFPandLPfriendship,thendirec-tionalityoffriendshipshouldnotberelevant.LonelinessintheFPandtheLPmoveupanddowntogetherinresponsetotheunob-servedfactors.Incontrast,ifanFPnamesanLPasafriendbuttheLPdoesnotreciprocate,thenacausalrelationshipindicatesthattheLPsignificantlyaffectstheFP,buttheFPdoesnotnecessarilyaffecttheLP.1TheKamada-Kawaialgorithmusedtopreparethe

1

Weexploredthesensitivityofourresultstomodelspecificationbyconductingnumerousotheranalyses,eachofwhichhadvariousstrengthsandlimitations,butnoneofwhichyieldedsubstantiallydifferentresultsthanthosepresentedhere.Forexample,weexperimentedwithdifferenterrorspecifications.AlthoughweidentifiedonlyasingleclosefriendformostoftheFPs,westudiedhowmultipleobservationsonsomeFPsaffectedthestandarderrorsofourmodels.Huber-Whitesandwichesti-mateswithclusteringontheFPsyieldedverysimilarresults.WealsotestedforthepresenceofserialcorrelationintheGEEmodelsusingaLagrangemultipliertestandfoundnoneremainingafterincludingthelaggeddependentvariable(Beck,2001).

STRUCTUREANDSPREADOFLONELINESS

981

imagesinFigure1generatesamatrixofshortestnetworkpathdistancesfromeachnodetoallothernodesinthenetworkandrepositionsnodessoastoreducethesumofthedifferencebetweentheplotteddistancesandthenetworkdistances(Kamada&Kawai,1989).Thefundamentalpatternoftiesinasocialnetwork(knownasthe“topology”)isfixed,buthowthispatternisvisuallyren-dereddependsontheanalyst’sobjectives.

Table3

MeanTotalNumberofSocialContactsforPeopleinEachoftheFourLonelinessCategories

Variable

FeltFeltFeltFelt

lonelylonelylonelylonely

0–11–23–45–7

daysdaysdaysdays

lastlastlastlast

weekweekweekweek

Mno.ofsocialcontacts(friendsandfamilycombined)

4.033.883.763.42

SE0.050.110.210.28

Results

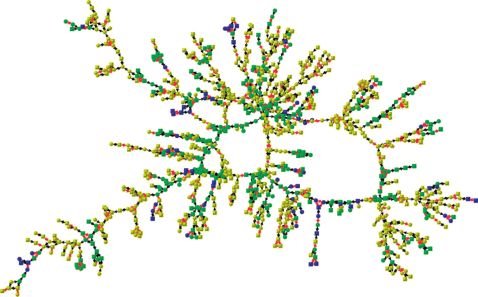

InFigure1,weshowaportionofthesocialnetwork,whichdemonstratesaclusteringofmoderatelylonely(greennodes)andverylonely(bluenodes)people,especiallyattheperipheryofthenetwork.Inthestatisticalmodels,therelationshipsbetweenlone-linessandnumberofsocialcontactsprovedtobenegativeandmonotonic,asillustratedinFigure1anddocumentedinTable3.TodeterminewhethertheclusteringoflonelypeopleshowninFigure1couldbeexplainedbychance,weimplementedthefollowingpermutationtest:Wecomparedtheobservednetworkwith1,000randomlygeneratednetworksinwhichwepreservedthenetworktopologyandtheoverallprevalenceoflonelinessbut

inwhichwerandomlyshuffledtheassignmentofthelonelinessvaluetoeachnode(Szabo&Barabasi,2007).Forthistest,wedichotomizedlonelinesstobezeroiftherespondentsaidtheywerelonely0–1daysthepreviousweek,andoneotherwise.Ifcluster-inginthesocialnetworkisoccurring,thentheprobabilitythatanLPislonely,giventhatanFPislonely,shouldbehigherintheobservednetworkthanintherandomnetworks.Thisprocedurealsoallowsustogenerateconfidenceintervalsandmeasurehowfar,intermsofsocialdistance,thecorrelationinloneliness

be-

Figure1.LonelinessclustersintheFraminghamSocialNetwork.Thisgraphshowsthelargestcomponentoffriends,spouses,andsiblingsatExam7(centeredontheyear2000).Thereare1,019individualsshown.Eachnoderepresentsaparticipant,anditsshapedenotesgender(circlesarefemale,squaresaremale).Linesbetweennodesindicaterelationship(redforsiblings,blackforfriendsandspouses).Nodecolordenotesthemeannumberofdaysthefocalparticipantandalldirectlyconnected(Distance1)linkedparticipantsfeltlonelyinthepastweek,withyellowbeing0–1days,greenbeing2days,andbluebeinggreaterthan3daysormore.Thegraphsuggestsclusteringinlonelinessandarelationshipbetweenbeingperipheralandfeelinglonely,bothofwhichareconfirmedbystatisticalmodelsdiscussedinthemaintext.

982

CACIOPPO,FOWLER,ANDCHRISTAKIS

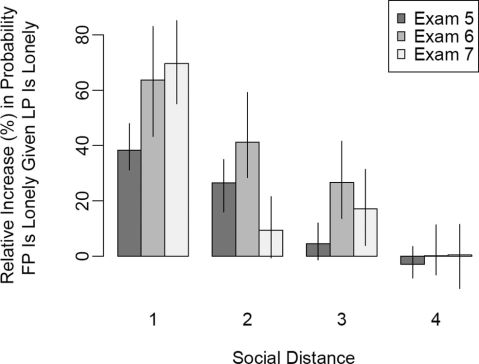

tweenFPandLPreaches.AsdescribedbelowandillustratedinFigure2,wefoundasignificantrelationshipbetweenFPandLPloneliness,andthisrelationshipextendsuptothreedegreesofseparation.Inotherwords,aperson’slonelinessdependsnotjustonhisfriend’slonelinessbutalsoextendstohisfriend’sfriendandhisfriend’sfriend’sfriend.Thefullnetworkshowsthatpartici-pantsare52%(95%CI?40%to65%)morelikelytobelonelyifapersontowhomtheyaredirectlyconnected(atonedegreeofseparation)islonely.Thesizeoftheeffectforpeopleattwodegreesofseparation(e.g.,thefriendofafriend)is25%(95%CI?14%to36%),andforpeopleatthreedegreesofseparation(e.g.,thefriendofafriendofafriend),itis15%(95%CI?6%to26%).Atfourdegreesofseparation,theeffectdisappears(2%;95%CI??5%to10%),inkeepingwiththe“threedegreesofinfluence”ruleofsocialnetworkcontagionthathasbeenexhibitedforobesity,smoking,andhappiness(e.g.,Christakis&Fowler,2007,2008;Fowler&Christakis,2008a).

ThefirstmodelinTable4,depictedinthefirstthreecolumns,showsthat(a)lonelinessinthepriorwavepredictslonelinessinthecurrentwave,and(b)currentfeelingsoflonelinessaremuchmorecloselytiedtoournetworksofoptionalsocialconnections,measuredatthepriorwave,thantothosethatarehandedtousuponbirthortodemographicfeaturesoftheindividuals.Peoplewithmorefriendsarelesslikelytoexperiencelonelinessinthefuture,andeachextrafriendappearstoreducethefrequencyoffeelinglonelyby0.04daysperweek.Thatmaynotseemlike

Figure2.SocialdistanceandlonelinessintheFraminghamSocialNet-work.Thisfigureshowsforeachexamthepercentageincreaseinthelikelihoodagivenfocalparticipant(FP)islonelyifafriendorfamilymemberatacertainsocialdistanceislonely(wherelonelyisdefinedasfeelinglonelymorethanonceaweek).Therelationshipisstrongestbetweenindividualswhoaredirectlyconnected,butitremainssignifi-cantlygreaterthanzeroatsocialdistancesuptothreedegreesofsepara-tion,meaningthataperson’slonelinessisassociatedwiththelonelinessofpeopleuptothreedegreesremovedfromtheminthenetwork.Valuesarederivedbycomparingtheconditionalprobabilityofbeinglonelyintheobservednetworkwithanidenticalnetwork(withtopologyandincidenceoflonelinesspreserved)inwhichthesamenumberoflonelyparticipantsarerandomlydistributed.Linkedparticipant(LP)socialdistancereferstoclosestsocialdistancebetweentheLPandFP(LP?Distance1,LP’sLP?Distance2,etc.).Errorbarsshow95%confidenceintervals.

much,butthereare52weeksinayear,sothisisequivalenttoabout2extradaysoflonelinessperyear;because,onaverage(inourdata)peoplefeellonely48daysperyear,havingacoupleofextrafriendsdecreaseslonelinessbyabout10%fortheaverageperson.Thesamemodelshowsthatthenumberoffamilymembershasnoeffectatall.

Analysesalsoshowedthatlonelinessshapessocialnetworks.Model2inTable4,depictedinthemiddlethreecolumns,showsthatpeoplewhofeellonelyatanassessmentarelesslikelytohavefriendsbythenextassessment.Infact,comparedwithpeoplewhoareneverlonely,theyloseabout8%oftheirfriendsonaveragebythetimetheytaketheirnextexaminroughly4years.Forcom-parison,andnotsurprisingly,theresultsdepictedinthethirdmodelinTable4(lastthreecolumns)showthatlonelinesshasnoeffectonthefuturenumberoffamilymembersapersonhas.Theseresultsaresymmetrictobothincomingandoutgoingties(notshown;availableonrequest).Lonelypeopletendtoreceivefewerfriendshipnominations,buttheyalsotendtonamefewerpeopleasfriends.Whatthismeansisthatlonelinessisbothacauseandaconsequenceofbecomingdisconnected.Theseresultssuggestthatouremotionsandnetworksreinforceeachotherandcreatearich-gets-richercyclethatbenefitsthosewiththemostfriends.Peoplewithfewfriendsaremorelikelytobecomelonelierovertime,whichthenmakesitlesslikelythattheywillattractortrytoformnewsocialties.

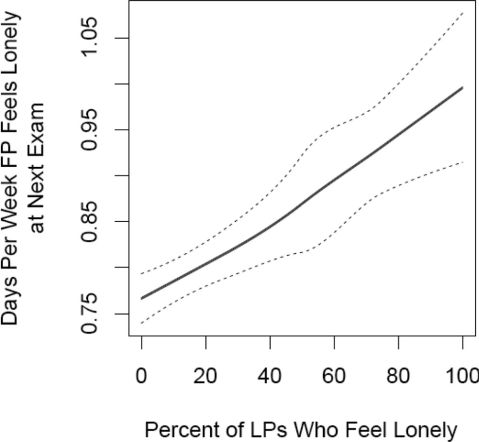

Wealsofindthatsocialconnectionsandthelonelinessofthepeopletowhomtheseconnectionsaredirectedinteracttoaffecthowpeoplefeel.Figure3showsthesmoothedbivariaterelation-shipbetweenthefractionofaperson’sfriendsandfamilywhoarelonelyatoneexamandthenumberofdaysperweekthatpersonfeelslonelyatthefollowingexam.Therelationshipissignificantandaddsanextraquarterdayoflonelinessperweektotheaveragepersonwhoissurroundedbyotherlonelypeople,comparedwiththosewhoarenotconnectedtoanyonewhoislonely.InTable5,wepresentastatisticalmodeloftheeffectoflonelyandnonlonelyLPsonfutureFPlonelinessthatincludescontrolsforage,educa-tion,andgender.ThismodelshowsthateachadditionallonelyLPsignificantlyincreasesthenumberofdaysaFPfeelslonelyatthenextexam(p?.001).Conversely,eachadditionalnonlonelyLPsignificantlyreducesthenumberofdaysaparticipantfeelslonelyatthenextexam(p?.002).Buttheseeffectsareasymmetric:LonelyLPsareabouttwoandahalftimesmoreinfluentialthannonlonelyLPs,andthedifferenceintheseeffectsizesisitselfsignificant(p?.01).Thus,thefeelingoflonelinessseemstospreadmoreeasilythanafeelingofbelonging.

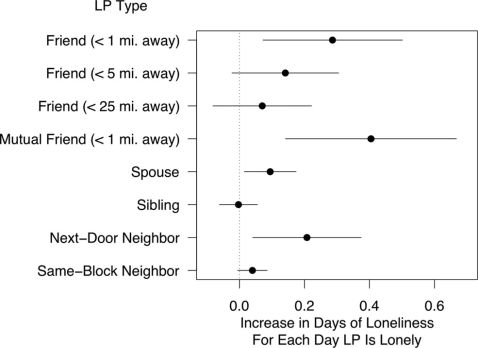

Tostudyperson-to-personeffects,weexaminedthedirecttiesandindividual-leveldeterminantsofFPloneliness.IntheGEEmodelswepresentinTables6–12,wecontrolforseveralfactors,asnotedearlier,andtheeffectofsocialinfluencefromonepersononanotheriscapturedbythe“Days/WeekLPCurrentlyLonely”coefficientinthefirstrow.Wehavehighlightedinboldthesocialinfluencecoefficientsthataresignificant.Figure4summarizestheresultsfromthesemodelsforfriends,spouses,siblings,andneigh-bors.Eachextradayoflonelinessina“nearby”friend(wholiveswithin1mile)increasesthenumberofdaysFPislonelyby0.29days(95%CI?0.07to0.50;seethefirstmodelinTable6).Incontrast,moredistantfriends(wholivemorethan1mileaway)havenosignificanteffectonFP,andtheeffectsizeappearstodeclinewithdistance(seethesecondmodelinTable6).

Among

STRUCTUREANDSPREADOFLONELINESS

983

Table4

ProspectiveInfluenceofFriendsandFamilyonLonelinessandViceVersa

Currentwave

Days/weekfeellonely

Variable

Priorwavedays/weekfeellonelyPriorwaveno.offriendsPriorwaveno.offamilyAge

YearsofeducationFemaleExam7ConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

Coef0.257?0.040?0.0010.006?0.0140.1240.0430.1125,0655,6566,083

SE0.0210.0130.0040.0010.0060.0240.0220.196

p.000.002.797.000.019.000.057.569

Coef?0.0100.900?0.003?0.0020.003?0.0160.0070.0927204,8666,083

No.offriends

SE0.0040.0070.0020.0000.0020.0090.0090.075

p.010.000.046.000.145.067.419.223

Coef?0.007?0.0290.9330.002?0.0050.0140.041?0.2751,28857,3496,083

No.offamily

SE0.0060.0070.0030.0010.0030.0120.0120.089

p.227.000.000.003.033.240.001.002

Note.Coef?coefficient.Resultsforlinearregressionoffocalparticipant’sloneliness,numberoffriends,andnumberoffamilymembersatcurrentexamonpriorloneliness,numberoffriends,andnumberoffamily,plusothercovariates.Modelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringonthefocalparticipantandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).Themainresults(coefficientsinbold)showthatnumberoffriendsisassociatedwithadecreaseinfutureloneliness,andlonelinessisassociatedwithadecreaseinfuturefriends.

friends,wecandistinguishadditionalpossibilities.Becauseeachpersonwasaskedtonameafriend,andnotallofthesenomina-tionswerereciprocated,wehaveFP-perceivedfriends(denoted“friends”),“LP-perceivedfriends”(LPnamedFPasafriend,butnotviceversa)and“mutualfriends”(FPandLPnominatedeach

other).NearbymutualfriendshaveastrongereffectthannearbyFP-perceivedfriends;eachdaytheyarelonelyadds0.41daysoflonelinessfortheFP(95%CI?0.14to0.67;seethethird

model

Table5

InfluenceofNumberofLonelyLinkedParticipantsonFocalParticipantLoneliness

Currentwavedays/weekfeel

lonely

Variable

PriorwavenumberoflonelyLPsPriorwavenumberofnonlonelyLPsPriorwavedays/weekfeellonelyAge

YearsofeducationFemaleExam7ConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

Coef0.064?0.0240.2300.003?0.0030.1210.0530.0373,4873,8314,879

SE0.0170.0080.0220.0020.0060.0250.0240.206

p.000.002.000.030.641.000.027.858

Figure3.Lonelylinkedparticipants(LPs)intheFraminghamSocialNetwork.ThisplotshowsthatthenumberofdaysperweekapersonfeelslonelyinExams6and7ispositivelyassociatedwiththefractionoftheirfriendsandfamilyinthepreviousexamwhoarelonely(thosewhosaytheyarelonelymorethanonedayaweek).ThesolidlineshowssmoothedrelationshipbasedonbivariateLOESSregression,anddottedlinesindicate95%confidenceintervals.Theresultsshowthatpeoplesurroundedbyotherlonelypeoplearethemselvesmorelikelytofeellonelyinthefuture.

Note.Coef?coefficient;LP?linkedparticipant.Resultsforlinearregres-sionoffocalparticipant’sloneliness,onpriorloneliness,numberoflonelyfriendsandfamily(?1dayoflonelinessperweek),numberofnonlonelyfriendsandfamily(0–1daysoflonelinessperweek),andothercovariates.Modelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringonthefocalparticipantandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).Themainresults(coefficientsinbold)showthatnumberoflonelyLPsisassociatedwithanincreaseinfuturelonelinessandthenumberofnonlonelyLPsisassociatedwithadecreaseinfutureloneliness.Moreover,thelonelyLPeffectissignificantlystrongerthanthenonlonelyLPeffect(p?.01,calculatedbydrawing1000pairsofcoefficientsfromthecoefficientcovariancematrixproducedbythemodel).

984

CACIOPPO,FOWLER,ANDCHRISTAKIS

Figure4.Linkedparticipant(LP)typeandlonelinessintheFraminghamSocialNetwork.Thisfigureshowsthatfriends,spouses,andneighborssignificantlyinfluenceloneliness,butonlyiftheyliveveryclosetothefocalparticipant.Effectsareestimatedusinggeneralizedestimatingequa-tionlinearmodelsonseveraldifferentsubsamplesoftheFraminghamSocialNetwork(seeTables6and7).

inthethirdcolumnofTable6).Incontrast,theinfluenceofnearbyLP-perceivedfriendsisnotsignificant(p?.25;seethefourthmodelinthefourthcolumnofTable6).Iftheassociationsinthesocialnetworkweremerelyduetoconfounding,thesignificanceandeffectsizesfordifferenttypesoffriendshipsshouldbesimilar.Thatis,ifsomethirdfactorwereexplainingbothFPandLPloneliness,itshouldnotrespectthedirectionalityorstrengthofthetie.

WealsofindsignificanteffectsforotherkindsofLPs.Eachdayacoresidentspouseislonelyyields0.10extradaysoflonelinessfortheFP(95%CI?0.02to0.17;seethefifthmodelinTable6),

whereasnoncoresidentspouseshavenosignificanteffect(seethesixthmodel).Next-doorneighborswhoexperienceanextradayoflonelinessincreaseFP’slonelinessby0.21days(95%CI?0.04to0.38;seethethirdmodelinthethirdcolumnofTable7),butthiseffectquicklydropsclosetozeroamongneighborswholiveonthesameblock(within25m;seethefourthmodelinTable7).Alltheserelationshipsindicatetheimportanceofphysicalproximity,andthestronginfluenceofneighborssuggeststhatthespreadoflonelinessmaypossiblydependmoreonfrequentsocialcontactinolderadults.Butsiblingsdonotappeartoaffectoneanotheratall(eventheoneswholivenearby;seethefirstmodelinTable7),whichprovidesadditionalevidencethatlonelinessinolderadultsisabouttherelationshipspeoplechoose,ratherthantherelation-shipstheyinherit.Andspousesappeartobeanintermediatecategory;Table8showsthatspousesaresignificantlylessinflu-entialthanfriendsinthespreadoflonelinessfrompersontoperson(asindicatedbythesignificantinteractionterminthefirstrowofTable8).

Analysesseparatedbygendersuggestedthatlonelinessspreadsmoreeasilyamongwomenthanamongmenandthatthisholdsforbothfriendsandneighbors.AsshowninthecoefficientsinthefirstrowofTables9and10,womenaremorelikelytobeaffectedbythelonelinessofboththeirfriends(seeTable9)andneighbors(seeTable10),andtheirlonelinessismorelikelytospreadtootherpeopleintheirsocialnetwork.ThecoefficientsinboldshowthatsocialinfluenceisgreatestwhentheFPortheLPisfemale.Womenalsoreportedhigherlevelsoflonelinessthandidmen.Wearereportingestimatesfromalinearmodel,however,sothebaselinerateoflonelinessshouldnotaffecttheabsolutediffer-encesthatweobserved.(Wewouldbemoreconcernedaboutthispossibleeffectifwewerereportingoddsratiosorriskratiosthataresensitivetothebaseline.)Inalinearmodel,anyadditivedifferencesinbaselineshouldbecapturedbythesexvariableinthemodel,whichdoesshowasignificantlyhigherbaselineforwomen.However,becauseweincludethiscontrol,the

baseline

Table6

AssociationofLPLonelinessandFPLoneliness

LPtype

Variable

Days/weekLPcurrentlylonelyDays/weekLPlonelyinpriorwaveDays/weekFPlonelyinpriorwaveExam7FP’sageFPfemale

FP’syearsofeducationConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

Nearbyfriend0.29(0.11)0.12(0.05)0.31(0.13)0.11(0.09)0.01(0.01)0.18(0.09)0.00(0.01)?0.30(0.43)

236375472

Distantfriend?0.08(0.05)0.11(0.05)0.39(0.09)0.05(0.07)0.01(0.01)0.06(0.08)?0.01(0.02)?0.04(0.60)

6778991,014

Nearbymutualfriend0.41(0.13)0.16(0.09)0.28(0.14)0.04(0.16)0.01(0.01)0.17(0.14)0.01(0.02)?0.78(0.60)

138285214

NearbyLP:Perceivedfriend0.35(0.30)0.02(0.08)0.10(0.05)?0.07(0.09)0.01(0.01)0.12(0.14)0.05(0.03)?0.89(0.71)

122145274

Coresidentspouse0.10(0.04)0.03(0.02)0.21(0.04)0.08(0.03)0.00(0.00)0.11(0.03)0.00(0.01)0.48(0.20)1,5751,7343,716

Noncoresident

spouse0.08(0.05)0.06(0.05)0.04(0.05)0.01(0.08)?0.01(0.00)0.04(0.08)?0.05(0.02)1.65(0.51)275290592

Note.LP?linkedparticipant;FP?focalparticipant.CoefficientsandstandarderrorsinparenthesesforlinearregressionofdaysperweekFPfeelslonelyoncovariatesareshown.Observationsforeachmodelarerestrictedbytypeofrelationship(e.g.,theleftmostmodelincludesonlyobservationsinwhichtheFPnamedtheLPasa“friend”inthepreviousandcurrentperiod,andthefriendis“nearby,”i.e.,livesnomorethan1mileaway).ModelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringontheFPandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).

STRUCTUREANDSPREADOFLONELINESS

985

Table7

AssociationofLPLonelinessandFPLoneliness

LPtype

Variable

Days/weekLPcurrentlylonelyDays/weekLPlonelyinpriorwaveDays/weekFPlonelyinpriorwaveExam7FP’sageFPfemale

FP’syearsofeducationConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

Nearbysibling0.00(0.03)?0.02(0.02)0.18(0.05)0.00(0.05)0.00(0.00)0.10(0.05)?0.01(0.02)0.82(0.43)1,0651,1402,124

Distantsibling?0.03(0.01)0.03(0.01)0.18(0.04)0.03(0.04)0.00(0.00)0.06(0.04)0.00(0.01)0.71(0.29)3,7293,9546,168

Immediateneighbor0.21(0.09)0.08(0.06)0.39(0.19)0.25(0.13)0.00(0.00)0.14(0.12)0.02(0.04)?0.33(0.68)

205366364

Neighborwithin

25m0.04(0.02)0.03(0.02)0.22(0.04)0.12(0.06)0.01(0.00)0.17(0.06)0.00(0.02)?0.01(0.34)1,6181,9301,904

Neighborwithin

100m?0.05(0.03)?0.02(0.03)0.08(0.06)?0.01(0.10)?0.01(0.01)0.22(0.09)0.01(0.02)1.02(0.39)5,7386,2786,888

Coworker0.00(0.03)?0.02(0.02)0.18(0.05)0.00(0.05)0.00(0.00)0.10(0.05)?0.01(0.02)0.82(0.43)6366651,330

Note.LP?linkedparticipant;FP?focalparticipant.CoefficientsandstandarderrorsinparenthesesforlinearregressionofdaysperweekFPfeelslonelyoncovariatesareshown.Observationsforeachmodelarerestrictedbytypeofrelationship(e.g.,theleftmostmodelincludesonlyobservationsinwhichtheFPnamedtheLPasa“sibling”inthepreviousandcurrentperiod,andthesiblingis“nearby,”i.e.,livesnomorethan1mileaway).ModelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringontheFPandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).

differenceinmenandwomenshouldnotaffecttheinterpretationoftheabsolutenumberofdayseachadditionaldayoflonelinessexperiencedbyanLPcontributestothelonelinessexperiencedbyanFP.

Finally,ourmeasureoflonelinesswasderivedfromthe“Ifeellonely”itemintheCES–D.ToaddresswhetherourresultswouldTable8

InfluenceofTypeofRelationshiponAssociationBetweenLPLonelinessandFPLoneliness

Variable

LPisSpouse?Days/WeekLPCurrentlyLonely

Days/weekLPcurrentlylonelyLPisspouse(insteadoffriend)Days/weekLPlonelyinpriorwaveDays/weekFPlonelyinpriorwaveExam7FP’sageFemale

FP’syearsofeducationConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

Coef?0.2740.3640.1650.0460.2270.0820.0000.117?0.0050.2329101,0562,094

SE0.1380.1310.0920.0220.0460.0310.0020.0320.0060.204

p.047.005.074.033.000.009.914.000.470.255

changeifdepressionwereincludedinthemodels,wecreatedadepressionindexbysummingtheother19questionsintheCES–D(droppingthequestiononloneliness).ThePearsoncorrelationbetweentheindicesinourdatais0.566.Ifdepressioniscausingthecorrelationinlonelinessbetweensocialcontacts,thenthecoefficientonLPlonelinessshouldbereducedtoinsignificancewhenweadddepressionvariablestothemodelsinTables6and7.Specifically,weaddedacontemporaneousandlaggedvariableforbothFP’sandLP’sdepression.TheresultsinTables11and12showthatthereisasignificantassociationbetweenFPcurrentdepressionandFPcurrentloneliness(theeighthrowinbold),butotherdepressionvariableshavenoeffect,andaddingthemtothemodelhaslittleeffectontheassociationbetweenFPandLPloneliness.Lonelinessinnearbyfriends,nearbymutualfriends,immediateneighbors,andnearbyneighborsallremainsignifi-cantlyassociatedwithFPloneliness.

Discussion

Thepresentresearchshowsthatwhatmightappeartobeaquintessentialindividualisticexperience—loneliness—isnotonlyafunctionoftheindividualbutisalsoapropertyofgroupsofpeople.Peoplewhoarelonelytendtobelinkedtootherswhoarelonely,aneffectthatisstrongerforgeographicallyproximalthandistantfriendsyetextendsuptothreedegreesofseparation(friends’friends’friends)withinthesocialnetwork.Thenatureofthefriendshipmatters,aswell,inthatnearbymutualfriendsshowstrongereffectsthannearbyordinaryfriends.Ifsomethirdfactorwereexplainingbothfocalandlinkedparticipants’loneliness,thenlonelinessshouldnotbecontingentonthedifferenttypesoffriendshiporthedirectionalityofthetie.Theseresults,therefore,argueagainstlonelinesswithinnetworksprimarilyreflectingsharedenvironments.

Longitudinalanalysesalsoindicatedthatnonlonelyindividualswhoarearoundlonelyindividualstendtogrowlonelierovertime.

Note.LP?linkedparticipant;FP?focalparticipant.ResultsforlinearregressionofdaysperweekFPfeelslonelyatnextexamoncovariatesareshown.Sampleincludesallspousesandnearbyfriends(nearby??1mileaway).Theinteractionterminthefirstrowteststhehypothesisthatspouseshavelessinfluencethanfriendsonloneliness.Modelswereesti-matedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringontheFPandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schild-crout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstruc-tureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).Theresultsshowthatspousesexertsignificantlylessinfluenceoneachotherthanfriends.

986

CACIOPPO,FOWLER,ANDCHRISTAKIS

Table9

AssociationofLPLonelinessandFPLonelinessinFriends,ByGender

LPtype?friendwithin2miles

Variable

Days/weekLPcurrentlylonelyDays/weekLPlonelyinpriorwaveDays/weekFPlonelyinpriorwaveExam7FP’sage

FP’syearsofeducationConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

FPmale0.03(0.03)0.04(0.04)0.35(0.18)0.16(0.09)0.01(0.01)?0.01(0.01)?0.33(0.57)

5773195

FPfemale0.33(0.15)0.01(0.05)0.37(0.11)0.12(0.12)0.00(0.01)0.00(0.02)?0.10(0.71)

142218194

LPmale0.02(0.05)0.05(0.07)0.36(0.19)0.15(0.10)0.01(0.01)?0.01(0.01)?0.46(0.63)

5872174

LPfemale0.25(0.13)0.01(0.04)0.38(0.11)0.13(0.11)0.00(0.01)0.01(0.02)0.09(0.64)144221215

FP&LPmale0.05(0.04)0.03(0.06)0.15(0.04)0.07(0.07)0.01(0.01)?0.02(0.01)0.09(0.52)

3842166

FP&LPfemale0.36(0.15)0.01(0.05)0.31(0.11)0.09(0.11)0.00(0.01)0.00(0.02)0.27(0.71)123190186

FP&LPoppositegender?0.02(0.11)0.04(0.07)0.79(0.21)0.41(0.26)0.02(0.02)0.05(0.03)?1.85(1.04)

235837

Note.LP?linkedparticipant;FP?focalparticipant.CoefficientsandstandarderrorsinparenthesesforlinearregressionofdaysperweekFPfeelslonelyoncovariatesareshown.Observationsforeachmodelarerestrictedbytypeofrelationship(e.g.,theleftmostmodelincludesonlyobservationsinwhichtheFPisamale);allLPsinthistablearefriendswholivewithintwomiles.ModelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringontheFPandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).

Thelongitudinalresultssuggestthatlonelinessappearsinsocialnetworksthroughtheoperationofinduction(e.g.,contagion),ratherthansimplyarisingfromlonelyindividualsfindingthem-selvesisolatedfromothersandchoosingtobecomeconnectedtootherlonelyindividuals(i.e.,thehomophilyhypothesis).Thepresentstudydoesnotpermitustoidentifytheextenttowhichtheemotional,cognitive,andbehavioralconsequencesoflonelinesscontributedtotheinductionofloneliness.Allthreecontagionprocessesarepromotedbyface-to-facecommunicationsanddis-closures,especiallybetweenindividualswhosharecloseties,andcanextendtofriends’friendsandbeyondthroughachainingoftheseeffects.Thesocialnetworkpatternoflonelinessandtheinterpersonalspreadoflonelinessthroughthenetworkthereforeappearmostconsistentwiththeinductionhypothesis.Iflonelinessiscontagious,what,ifanything,keepstheconta-gionincheck?AnobservationbyHarlowetal.(1965)intheirstudiesofsocialisolationinrhesusmonkeysoffersaclue.Whentheisolatemonkeyswerereintroducedintothecolony,Harlowetal.,notedthatmostoftheseisolateanimalsweredrivenofforeliminated.Ourresultssuggestthathumansmaysimilarlydriveawaylonelymembersoftheirspeciesandthatfeelingsociallyisolatedcanleadtoonebecomingobjectivelyisolated.Lonelinessnotonlyspreadsfrompersontopersonwithinasocialnetworkbutitalsoreducesthetiesoftheseindividualstootherswithinthenetwork.Asaresult,lonelinessisfoundinclusterswithinsocialnetworks,isdisproportionatelyrepresentedattheperipheryofsocialnetworks,andthreatensthecohesivenessofthenetwork.Thecollectiverejectionofisolatesobservedinhumansandother

Table10

AssociationofLPLonelinessandFPLonelinessinNeighbors,ByGender

LPtype?neighborwithin25m

Variable

Days/weekLPcurrentlylonelyDays/weekLPlonelyinpriorwaveDays/weekFPlonelyinpriorwaveExam7FP’sage

FP’syearsofeducationConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

FPmale0.05(0.06)0.00(0.02)0.16(0.06)0.18(0.08)0.00(0.00)0.02(0.02)0.04(0.40)127137353

FPfemale0.19(0.08)0.07(0.05)0.27(0.07)0.02(0.19)?0.01(0.01)?0.03(0.04)1.25(1.02)571684535

LPmale?0.06(0.04)0.05(0.04)0.20(0.07)0.04(0.14)0.00(0.01)?0.01(0.03)0.84(0.69)244264352

LPfemale0.14(0.06)0.06(0.05)0.31(0.07)0.16(0.11)0.00(0.01)?0.02(0.03)0.76(0.72)473574536

FP&LPmale0.00(0.06)0.02(0.03)0.14(0.07)0.18(0.08)0.00(0.01)0.03(0.02)?0.23(0.57)

2629140

FP&LPfemale0.24(0.09)0.08(0.07)0.31(0.08)0.10(0.17)0.00(0.01)?0.04(0.05)1.12(1.23)350454323

FP&LPoppositegender0.01(0.06)0.02(0.03)0.20(0.06)0.06(0.12)0.00(0.00)?0.01(0.02)0.86(0.52)318342425

Note.LP?linkedparticipant;FP?focalparticipant.CoefficientsandstandarderrorsinparenthesesforlinearregressionofdaysperweekFPfeelslonelyoncovariatesareshown.Observationsforeachmodelarerestrictedbytypeofrelationship(e.g.,theleftmostmodelincludesonlyobservationsinwhichtheFPisamale);allLPsinthistablearenonrelatedneighborswholivewithin25m.ModelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringontheFPandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).

STRUCTUREANDSPREADOFLONELINESS

987

Table11

AssociationofLPLonelinessandFPLonelinessControllingforDepression(CompareWithTable6)

LPtype

Variable

Days/weekLPcurrentlylonelyDays/weekLPlonelyinpriorwaveDays/weekFPlonelyinpriorwaveExam7FP’sageFPfemale

FP’syearsofeducationFPcurrentdepressionindex

FPdepressionindexinpriorwaveLPcurrentdepressionindex

LPdepressionindexinpriorwaveConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

Nearbyfriend0.28(0.12)0.13(0.07)0.13(0.13)?0.03(0.09)0.00(0.00)?0.01(0.08)?0.01(0.02)0.07(0.02)0.00(0.02)?0.01(0.01)?0.02(0.01)0.11(0.41)157353396

Distantfriend?0.09(0.06)0.07(0.05)0.14(0.07)?0.08(0.09)0.01(0.01)0.01(0.07)0.01(0.02)0.08(0.01)?0.01(0.01)0.01(0.01)?0.01(0.01)?0.44(0.54)

405765826

Nearbymutualfriend0.37(0.15)0.13(0.12)0.17(0.17)?0.18(0.13)0.01(0.01)?0.07(0.15)0.01(0.02)0.07(0.04)?0.01(0.02)?0.02(0.02)?0.01(0.01)?0.25(0.70)

87266182

NearbyLP:Perceivedfriend0.33(0.28)0.02(0.07)0.05(0.06)?0.24(0.11)0.02(0.01)0.11(0.14)0.04(0.02)0.06(0.02)?0.02(0.01)0.00(0.01)0.00(0.01)?1.23(0.57)

80126232

Coresidentspouse0.03(0.04)0.01(0.02)0.11(0.04)0.00(0.03)0.00(0.00)0.05(0.03)0.01(0.01)0.05(0.01)0.00(0.00)0.01(0.00)0.00(0.00)?0.07(0.20)

9591,4223,040

Noncoresident

spouse?0.05(0.07)?0.03(0.04)0.00(0.06)?0.07(0.09)0.00(0.00)0.00(0.07)?0.02(0.01)0.06(0.02)0.00(0.01)0.01(0.01)0.00(0.01)0.47(0.35)146219492

Note.LP?linkedparticipant;FP?focalparticipant.CoefficientsandstandarderrorsinparenthesesforlinearregressionofdaysperweekFPfeelslonelyoncovariatesareshown.Observationsforeachmodelarerestrictedbytypeofrelationship(e.g.,theleftmostmodelincludesonlyobservationsinwhichtheFPnamedtheLPasa“friend”inthepreviousandcurrentperiod,andthefriendis“nearby,”i.e.,livesnomorethan1mileaway).ModelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringontheFPandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).

primatesmaythereforeservetoprotectthestructuralintegrityofsocialnetworks.

Inthepresentstudy,thefindingthatlonelinessspreadsmorequicklyamongfriendsthanfamilyfurthersuggeststhattherejec-tionofisolatestoprotectsocialnetworksoccursmoreforciblyinnetworksthatweselect,ratherthaninthoseweinherit.Thiseffectmaybelimitedtoolderpopulations,however.Themeanageinoursamplewas64years,andelderlyadultshavebeenfoundtoreducethesizeoftheirnetworkstofocusonthoserelationshipsthatarerelativelyrewarding,withcostlyfamilytiesamongthosethataretrimmed(Carstensen,2001).Althoughaspouse’slonelinesswasrelatedtoanindividual’ssubsequentloneliness,friendsappeared

Table12

AssociationofLPLonelinessandFPLonelinessControllingForDepression(CompareWithTable7)

LPtype

Variable

Days/weekLPcurrentlylonelyDays/weekLPlonelyinpriorwaveDays/weekFPlonelyinpriorwaveExam7FP’sageFPfemale

FP’syearsofeducationFPcurrentdepressionindex

FPdepressionindexinpriorwaveLPcurrentdepressionindex

LPdepressionindexinpriorwaveConstantDevianceNulldevianceN

Nearbysibling0.00(0.03)?0.02(0.02)0.18(0.05)0.00(0.05)0.00(0.00)0.10(0.05)?0.01(0.02)0.07(0.02)0.00(0.02)?0.01(0.01)?0.02(0.01)0.82(0.43)6599911,748

Distantsibling?0.03(0.01)0.03(0.01)0.18(0.04)0.03(0.04)0.00(0.00)0.06(0.04)0.00(0.01)0.08(0.01)?0.01(0.01)0.01(0.01)?0.01(0.01)0.71(0.29)2,1143,1275,054

Immediateneighbor0.21(0.09)0.08(0.06)0.39(0.19)0.25(0.13)0.00(0.00)0.14(0.12)0.02(0.04)0.07(0.04)?0.01(0.02)?0.02(0.02)?0.01(0.01)?0.33(0.68)

103360300

Neighborwithin

25m0.04(0.02)0.03(0.02)0.22(0.04)0.12(0.06)0.01(0.00)0.17(0.06)0.00(0.02)0.06(0.02)?0.02(0.01)0.00(0.01)0.00(0.01)?0.01(0.34)

8961,6991,562

Neighborwithin

100m?0.05(0.03)?0.02(0.03)0.08(0.06)?0.01(0.10)?0.01(0.01)0.22(0.09)0.01(0.02)0.05(0.01)0.00(0.00)0.01(0.00)0.00(0.00)1.02(0.39)3,3235,2445,540

Coworker0.00(0.03)?0.02(0.02)0.18(0.05)0.00(0.05)0.00(0.00)0.10(0.05)?0.01(0.02)0.06(0.02)0.00(0.01)0.01(0.01)0.00(0.01)0.82(0.43)3016301,140

Note.LP?linkedparticipant;FP?focalparticipant.CoefficientsandstandarderrorsinparenthesesforlinearregressionofdaysperweekFPfeelslonelyoncovariatesareshown.Observationsforeachmodelarerestrictedbytypeofrelationship(e.g.,theleftmostmodelincludesonlyobservationsinwhichtheFPnamedtheLPasa“sibling”inthepreviousandcurrentperiod,andthesiblingis“nearby,”i.e.,livesnomorethan1mileaway).ModelswereestimatedusingageneralestimatingequationwithclusteringontheFPandanindependentworkingcovariancestructure(Liang&Zeger,1986;Schildcrout&Heagerty,2005).Modelswithanexchangeablecorrelationstructureyieldedpoorerfit.Fitstatisticsshowsumofsquareddeviancebetweenpredictedandobservedvaluesforthemodelandanullmodelwithnocovariates(Wei,2002).

988

CACIOPPO,FOWLER,ANDCHRISTAKIS

tohavemoreimpactonlonelinessthandidspouses.Thegenderdifferencesweobservedmaycontributetothisfinding.Wheeleretal.(1983)reportedthatlonelinessisrelatedtohowmuchtimemaleandfemaleparticipantsinteractwithwomeneachday,andwefoundthatthespreadoflonelinesswasstrongerforwomenthanformen.Researchisneededtoaddresswhethertheabsenceofaneffectofspousesandfamilymembersonthelonelinessismoretypicalofolderthanyoungeradultsandwomenthanmen.FowlerandChristakis(2008a)foundthathappinessalsooc-curredinclustersandspreadthroughnetworks.Severalimportantdifferenceshaveemergedintheinductionofhappinessandtheinductionofloneliness,however.First,FowlerandChristakis(2008)foundhappinesstobemorelikelythanunhappinesstospreadthroughsocialnetworks.Thepresentresearch,incontrast,indicatesthatthespreadoflonelinessismorepowerfulthanthespreadofnonloneliness.Negativeeventstypicallyhavemorepowerfuleffectsthanpositiveevents(i.e.,differentialreactivity;Cacioppo&Gardner,1999),soFowlerandChristakis’s(2008)findingsaboutthespreadofhappinessthroughsocialnetworksisdistinctive.Whereaslaboratorystudiesaredesignedtogaugedifferentialreactivitytoapositiveornegativeevent,theFowlerandChristakis(2008)studyalsoreflectspeople’sdifferentialexposuretohappyandunhappyevents.Thus,happinessmayspreadthroughnetworksmorethanunhappinessbecausepeoplehavemuchmorefrequentexposurestofriendsexpressinghappi-nessthanunhappiness.

Lonelinessdoesnothaveabipolaroppositelikehappiness,but,rather,islikehunger,thirst,andpaininthatitsabsenceisthenormalcondition,ratherthananevocativestate(Cacioppo&Patrick,2008).Furthermore,asanaversivestate,lonelinessmaymotivatepeopletoseeksocialconnection(whatevertheresponseofotherstosuchovertures),whichhastheeffectofincreasingthelikelihoodthatthoseproximaltoalonelyindividualwillbeex-posedtoloneliness.Together,theseprocessesmaymakeloneli-nessmorecontagiousthannonloneliness.

Aseconddifferencebetweenthespreadofhappinessandlone-linessconcernstheeffectofgender.FowlerandChristakis(2008)foundnogenderdifferencesinthespreadofhappiness,whereaswefoundthatlonelinessspreadsmuchmoreeasilyamongwomenthanamongmen.Womenmaybemorelikelytoexpressandsharetheiremotionsandmaybemoreattentivetotheemotionsofothers(Hatfieldetal.,1994),butthespreadofhappiness,aswellasloneliness,wouldbefosteredsimilarlyamongwomenwerethisasufficientcause.Thereisalsoastigmaassociatedwithloneliness,particularlyamongmen;womenaremorelikelytoengageinintimatedisclosuresthanaremen;andrelationalconnectednessismoreimportantforwomenthanformen(Brewer&Gardner,1996;Hawkleyetal.,2005;Shaver&Brennan,1991).Theseprocessesmayexplainthegreaterspreadoflonelinessamongwomenrelativetomen.Thepresentresults,however,clearlyshowthatgender,likeproximityandtypeofrelationship,influencesthespreadofloneliness.

Alimitationofallsocialnetworkanalysesisthatthestudiesarenecessarilyboundtheirsample.ThecompactnatureoftheFra-minghampopulationintheperiodfrom1971to2007andthegeographicalproximityoftheinfluencemitigatethisconstraint,butweneverthelessconsideredwhethertheresultsmighthavechangedwithalargersampleframethatincludesallnamedindi-vidualswhowerethemselvesnotparticipantsintheFraminghamHeartStudy.Forinstance,wecalculatedthestatisticalrelationshipbetweenthetendencytonamepeopleoutsidethestudyandlone-liness.APearsoncorrelationbetweenthenumberofcontactsnamedoutsidethestudyandlonelinessisnotsignificantandactuallyflipssignsfromoneexamtoanother(Exam6,0.016,p?.39;Exam7,?0.011,p?.53).Thisresultsuggeststhatthesamplingframeisnotbiasingtheaverageleveloflonelinessinthetargetindividualswearestudying.

Asecondpossiblelimitationisthatweincludedallparticipantsintheanalysis.ItispossiblethatthedeathorlossofcertaincriticalsocialnetworkmembersduringthestudysystematicallyaffecthowlonelyFPsfeltacrosstime.Toaddressthispossibility,werestrictedanalysistothoseindividuals(bothFPsandLPs)whoremainedaliveattheendofthestudy.Ifdeathistheonlyormostimportantsourceofnetworklossthatcausestheassociationbe-tweenFPandLPloneliness,thenremovingobservationsofpeoplewhodiedduringthestudyshouldreducetheassociationtoinsig-nificance.ResultsoftheseanalysesshowthattherestrictionhasnoeffectontheassociationbetweenFPandLPloneliness.Lonelinessinnearbyfriends,nearbymutualfriends,spouses,andimmediateneighborsallremainsignificantlyassociatedwithFPloneliness.Thedeathofcriticalnetworkmembers,therefore,doesnotappeartoaccountforourresults.

Priorresearchhasshownthatdisabilityisapredictoroflone-liness(Hawkleyetal.,2008).Arelatedissue,therefore,iswhetherthedisabilitystatusofFPsfactorintoourfindings.Toaddressthisissue,wecreatedadisabilityindexbysummingfivequestionsfromtheKatzIndexofActivitiesofDailyLiving(Spector,Katz,Murphy,&Fulton,1987)aboutthesubjects’abilitytoindepen-dentlydressthemselves,bathethemselves,eatanddrink,getintoandoutofachair,andusethetoilet.ThePearsoncorrelationbetweentheindicesinourdatais0.06(ns).Ifdisabilitiesaffectthecorrelationinlonelinessbetweensocialcontacts,thenthecoeffi-cientonLPlonelinessmaybereducedtoinsignificancewhenweadddisabilityvariablestothemodelsinTables6and7.Specifi-cally,weaddedacontemporaneousandlaggedvariableforbothFP’sandLP’sdisabilityindex.Theresultsoftheseancillaryanalysesindicatedthatlonelinessinnearbyfriends,nearbymutualfriends,immediateneighbors,andnearbyneighborsallremainsignificantlyassociatedwithFPloneliness.Thus,disabilitydoesnotappeartoaccountforourfindings.

Inconclusion,theobservationthatlonelinesscanbepassedfrompersontopersonisreminiscentofsociologistEmileDurkheim’s(1951)famousobservationaboutsuicide.Henoticedthatsuicideratesstayedthesameacrosstimeandacrossgroups,eventhoughtheindividualmembersofthosegroupscameandwent.Inotherwords,whetherpeopletooktheirownlivesde-pendedonthekindofsocietytheyinhabited.Althoughsuicide,likeloneliness,hasoftenbeenregardedasentirelyindividualistic,Durkheim’sworkindicatesthatsuicideisdriveninpartbylargersocialforces.Althoughlonelinesshasaheritablecomponent,thepresentstudyshowsitalsotobeinfluencedbybroadersocialnetworkprocesses.Indeed,wedetectedanextraordinarypatternattheedgeofthesocialnetwork.Ontheperiphery,peoplehavefewerfriends,whichmakesthemlonely,butitalsodrivesthemtocutthefewtiesthattheyhaveleft.Butbeforetheydo,theytendtotransmitthesamefeelingoflonelinesstotheirremainingfriends,startingthecycleanew.Thesereinforcingeffectsmeanthatoursocialfabriccanfrayattheedges,likeayarnthatcomes

STRUCTUREANDSPREADOFLONELINESS

989

looseattheendofacrochetedsweater.Animportantimplicationofthisfindingisthatinterventionstoreducelonelinessinoursocietymaybenefitbyaggressivelytargetingthepeopleintheperipherytohelprepairtheirsocialnetworks.Byhelpingthem,wemightcreateaprotectivebarrieragainstlonelinessthatcankeepthewholenetworkfromunraveling.

References

Adam,E.K.,Hawkley,L.C.,Kudielka,B.M.,&Cacioppo,J.T.(2006).Day-to-daydynamicsofexperience–cortisolassociationsinapopulation-basedsampleofolderadults.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica,103(45),17058–17063.

Akerlind,I.,&Hornquist,J.O.(1992).Lonelinessandalcoholabuse:Areviewofevidencesofaninterplay.SocialScienceandMedicine,34(4),405–414.Andersson,L.(1998).Lonelinessresearchandinterventions:Areviewoftheliterature.Aging&MentalHealth,2(4),264–274.

Bartels,M.,Cacioppo,J.T.,Hudziak,J.J.,&Boomsma,D.I.(2008).Geneticandenvironmentalcontributionstostabilityinlonelinessthroughoutchildhood.AmericanJournalofMedicalGeneticsPartB(NeuropsychiatricGenetics),147(3),385–391.

Beck,N.(2001).Time-series-cross-sectiondata:Whathavewelearnedinthepastfewyears?AnnualReviewofPoliticalScience,4(1),271–293.Berscheid,E.(1985).Interpersonalattraction.InG.Lindzey&E.Aronson(Eds.),Thehandbookofsocialpsychology(3rded.,pp.413–484).NewYork:RandomHouse.

Berscheid,E.,&Reis,H.T.(1998).Attractionandcloserelationships.InD.T.Gilbert,S.T.Fiske,&G.Lindzey(Eds.),Thehandbookofsocialpsychology(4thed.,Vol.2,pp.193–281).NewYork:McGrawHill.Bondevik,M.,&Skogstad,A.(1998).Theoldestold,ADL,socialnetwork,andloneliness.WesternJournalofNursingResearch,20(3),325–343.

Boomsma,D.I.,Cacioppo,J.T.,Muthen,B.,Asparouhov,T.,&Clark,S.(2007).LongitudinalgeneticanalysisforlonelinessinDutchtwins.TwinResearchandHumanGenetics,10(2),267–273.

Boomsma,D.,Cacioppo,J.,Slagboom,P.,&Posthuma,D.(2006).Ge-neticlinkageandassociationanalysisforlonelinessinDutchtwinandsiblingpairspointstoaregiononchromosome12q23–24.BehaviorGenetics,36(1),137–146.

Boomsma,D.,Willemsen,G.,Dolan,C.,Hawkley,L.,&Cacioppo,J.(2005).Geneticandenvironmentalcontributionstolonelinessinadults:TheNeth-erlandsTwinRegisterStudy.BehaviorGenetics,35(6),745–752.

Brewer,M.B.,&Gardner,W.(1996).Whoisthis“we”?Levelsofcollectiveidentityandselfrepresentations.JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,71,83–93.

Burt,R.S.(1986).Strangers,friends,andhappiness.InGSSTechnicalReportNo.72.Chicago:NationalOpinionResearchCenter,UniversityofChicago.

Byrne,D.(1971).Theattractionparadigm.NewYork:AcademicPress.Cacioppo,J.T.,&Gardner,W.L.(1999).Emotion.AnnualReviewofPsychology,50,191–214.

Cacioppo,J.T.,Hawkley,L.C.,Berntson,G.G.,Ernst,J.M.,Gibbs,A.C.,Stickgold,R.,etal.(2002).Dolonelydaysinvadethenights?Potentialsocialmodulationofsleepefficiency.PsychologicalScience,13(4),384–387.

Cacioppo,J.T.,Hawkley,L.C.,Crawford,L.E.,Ernst,J.M.,Burleson,M.H.,Kowalewski,R.B.,etal.(2002).Lonelinessandhealth:Potentialmechanisms.PsychosomaticMedicine,64(3),407–417.

Cacioppo,J.T.,Hawkley,L.C.,Ernst,J.M.,Burleson,M.,Berntson,G.G.,Nouriani,B.,etal.(2006).Lonelinesswithinanomologicalnet:Anevolution-aryperspective.JournalofResearchinPersonality,40(6),1054–1085.

Cacioppo,J.T.,&Patrick,B.(2008).Loneliness:Humannatureandtheneedforsocialconnection.NewYork:Norton.

Carrington,P.J.,Scott,J.,&Wasserman,S.(2005).Modelsandmethods

insocialnetworkanalysis.Cambridge,UnitedKingdom:CambridgeUniversityPress.

Carstensen,L.L.(2001).Selectivitytheory:Socialactivityinlife-spancontext.InA.J.Walker,M.Manoogian-O’Dell,A.McGraw,&D.L.G.White(Eds.),Familiesinlaterlife(pp.265–275).ThousandOaks,CA:PineForgePress.

Caspi,A.,Harrington,H.,Moffitt,T.E.,Milne,B.J.,&Poulton,R.(2006).Sociallyisolatedchildren20yearslater:Riskofcardiovasculardisease.ArchivesofPediatricandAdolescentMedicine,160(8),805–811.

Christakis,N.A.,&Fowler,J.H.(2007).Thespreadofobesityinalargesocialnetworkover32years.NewEnglandJournalofMedicine,357(4),370–379.

Christakis,N.A.,&Fowler,J.H.(2008).Thecollectivedynamicsofsmokinginalargesocialnetwork.NewEnglandJournalofMedicine,358(21),2249–2258.

Cole,S.W.,Hawkley,L.C.,Arevalo,J.M.,Sung,C.Y.,Rose,R.M.,&Cacioppo,J.T.(2007).Socialregulationofgeneexpressioninhumanleukocytes.GenomeBiology,8(9),R189.181–R189.113.

Cupples,L.A.,&D’Agnostino,R.B.(1988).Survivalfollowinginitialcardiovascularevents:30yearfollow-up.InW.B.Kannel,P.A.Wolf,&R.J.Garrison(Eds.),TheFraminghamStudy:Anepidemiologicalinvestigationofcardiovasculardisease(pp.88–2969).Bethesda,MD:NationalHeart,LungandBloodInstitute.

Cutrona,C.E.(1982).Transitiontocollege:Lonelinessandtheprocessofsocialadjustment.InL.A.Peplau&D.Perlman(Eds.),Loneliness:Asourcebookofcurrenttheory,research,andtherapy(pp.291–309).NewYork:Wiley.

Dronjak,S.,Gavrilovic,L.,Filipovic,D.,&Radojcic,M.B.(2004).Immobilizationandcoldstressaffectsympatho-adrenomedullarysystemandpituitary-adrenocorticalaxisofratsexposedtolong-termisolationandcrowding.PhysiologyandBehavior,81(3),409–415.

Dugan,E.,&Kivett,V.R.(1994).Theimportanceofemotionalandsocialisolationtolonelinessamongveryoldruraladults.Gerontologist,34(3),340–346.

Durkheim,E.(1951).Suicide:Astudyinsociology.NewYork:FreePress.Dykstra,P.A.,&deJongGierveld,J.(1999).[Differentialindicatorsoflonelinessamongelderly.Theimportanceoftypeofpartnerrelationship,partnerhistory,health,socioeconomicstatusandsocialrelations].Tijd-schriftVoorGerontologieEnGeriatrie,30(5),212–225.

Emler,N.(1994).Gossip,reputationandadaptation.InR.F.Goodman&A.Ben-Ze’ev(Eds.),Goodgossip(pp.34–46).Lawrence:UniversityofKansasPress.

Fitzpatrick,G.L.,&Modlin,M.J.(1986).Direct-linedistances:Interna-tionaledition.Metuchen,NJ:ScarecrowPress.

Fowler,J.H.,&Christakis,N.A.(2008a).Dynamicspreadofhappinessinalargesocialnetwork:Longitudinalanalysisover20yearsintheFraminghamHeartStudy.BritishMedicalJournal,337,a2338.

Fowler,J.H.,&Christakis,N.A.(2008b).Estimatingpeereffectsonhealthinsocialnetworks:AresponsetoCohen-ColeandFletcher;andTrogdon,Non-nemaker,andPais.JournalofHealthEconomics,27(5),1400–1405.

Harlow,H.F.,Dodsworth,R.O.,&Harlow,M.K.(1965).Totalsocialisolationinmonkeys.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica,54(1),90–97.

Hatfield,E.,Cacioppo,J.T.,&Rapson,R.L.(1994).Emotionalconta-gion.NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress.

Hawkley,L.C.,Browne,M.W.,&Cacioppo,J.T.(2005).HowcanIconnectwiththee?Letmecounttheways.PsychologicalScience,16(10),798–804.

Hawkley,L.C.,Hughes,M.E.,Waite,L.J.,Masi,C.M.,Thisted,R.A.,&Cacioppo,J.T.(2008).Fromsocialstructurefactorstoperceptionsofrelation-shipqualityandloneliness:TheChicagoHealth,Aging,andSocialRelationsStudy.JournalofGerontology:SocialSciences,63B,S375–S384.

Hawkley,L.C.,Masi,C.M.,Berry,J.D.,&Cacioppo,J.T.(2006).Lonelinessisauniquepredictorofage-relateddifferencesinsystolicbloodpressure.PsychologyandAging,21(1),152–164.

990

CACIOPPO,FOWLER,ANDCHRISTAKIS

Hector-Taylor,L.,&Adams,P.(1996).StateversustraitlonelinessinelderlyNewZealanders.PsychologicalReports,78,1329–1330.

Heikkinen,R.-L.,&Kauppinen,M.(2004).Depressivesymptomsinlatelife:A10-yearfollow-up.ArchivesofGerontologyandGeriatrics,38(3),239–250.

Holmen,K.,Ericsson,K.,Andersson,L.,&Winblad,B.(1992).Subjectiveloneliness:Acomparisonbetweenelderlyandrelatives.VardiNorden,12(2),9–13.

House,J.S.,Landis,K.R.,&Umberson,D.(1988,July29).Socialrelationshipsandhealth.Science,241(4865),540–545.

Jones,D.C.(1992).Parentaldivorce,familyconflictandfriendshipnetworks.JournalofSocialandPersonalRelationships,9(2),219–235.Kahneman,D.,Krueger,A.B.,Schkade,D.A.,Schwarz,N.,&Stone,A.A.(2004,December3).Asurveymethodforcharacterizingdailylifeexperience:Thedayreconstructionmethod.Science,306(5702),1776–1780.

Kamada,T.,&Kawai,S.(1989).Analgorithmfordrawinggeneralundirectedgraphs.InformationProcessingLetters,31(1),7–15.

Kanitz,E.,Tuchscherer,M.,Puppe,B.,Tuchscherer,A.,&Stabenow,B.(2004).Consequencesofrepeatedearlyisolationindomesticpiglets(Susscrofa)ontheirbehavioural,neuroendocrine,andimmunologicalresponses.Brain,Behavior,andImmunity,18(1),35–45.

Kannel,W.B.,Feinleib,M.,McNamara,P.M.,Garrison,R.J.,&Castelli,W.P.(1979).Aninvestigationofcoronaryheartdiseaseinfamilies.TheFraminghamOffspringStudy.AmericanJournalofEpidemiology,110(3),281–290.

Kiecolt-Glaser,J.K.,Ricker,D.,George,J.,Messick,G.,Speicher,C.E.,Garner,W.,etal.(1984).Urinarycortisollevels,cellularimmunocom-petency,andlonelinessinpsychiatricinpatients.PsychosomaticMedi-cine,46(1),15–23.

King,G.,Tomz,M.,&Wittenberg,J.(2000).Makingthemostofstatis-ticalanalyses:Improvinginterpretationandpresentation.AmericanJournalofPoliticalScience,44(2),341–355.

Lauder,W.,Mummery,K.,Jones,M.,&Caperchione,C.(2006).Acomparisonofhealthbehavioursinlonelyandnon-lonelypopulations.Psychology,Health&Medicine,11(2),233–245.

Liang,K.-Y.,&Zeger,S.L.(1986).Longitudinaldataanalysisusinggeneralizedlinearmodels.Biometrika,73(1),13–22.

Lyons,D.M.,Ha,C.M.,&Levine,S.(1995).Socialeffectsandcircadianrhythmsinsquirrelmonkeypituitary-adrenalactivity.HormonesandBehavior,29(2),177–190.

McGuire,S.,&Clifford,J.(2000).Geneticandenvironmentalcontribu-tionstolonelinessinchildren.PsychologicalScience,11(6),487–491.McPherson,M.,Smith-Lovin,L.,&Cook,J.M.(2001).Birdsofafeather:Homophilyinsocialnetworks.AnnualReviewofSociology,27(1),415.Mullins,L.C.,&Dugan,E.(1990).Theinfluenceofdepression,andfamilyandfriendshiprelations,onresidents’lonelinessincongregatehousing.Gerontologist,30(3),377–384.

Myers,D.G.,&Diener,E.(1995).Whoishappy?PsychologicalScience,6(1),10–19.

Nation,D.A.,Gonzales,J.A.,Mendez,A.J.,Zaias,J.,Szeto,A.,Brooks,L.G.,etal.(2008).TheeffectofsocialenvironmentonmarkersofvascularoxidativestressandinflammationintheWatanabeheritablehyperlipidemicrabbit.PsychosomaticMedicine,70(3),269–275.

Neimeyer,R.A.,&Mitchell,K.A.(1988).Similarityandattraction:Alongitudinalstudy.JournalofSocialandPersonalRelationships,5(2),131–148.

Nonogaki,K.,Nozue,K.,&Oka,Y.(2007).SocialisolationaffectsthedevelopmentofobesityandType2diabetesinmice.Endocrinology,148(10),4658–4666.

Penninx,B.W.,vanTilburg,T.,Kriegsman,D.M.,Deeg,D.J.,Boeke,A.J.,&vanEijk,J.T.(1997).Effectsofsocialsupportandpersonalcopingresourcesonmortalityinolderage:TheLongitudinalAgingStudyAm-sterdam.AmericanJournalofEpidemiology,146(6),510–519.

Peplau,L.,&Perlman,D.(1982).Perspectivesonloneliness.InL.Peplau

&D.Perlman(Eds.),Loneliness:Asourcebookofcurrenttheory,researchandtherapy(pp.1–18).NewYork:Wiley.

Pinquart,M.,&Sorenson,S.(2003).Riskfactorsforlonelinessinadult-hoodandoldage:Ameta-analysis.InS.P.Shohov(Ed.),Advancesinpsychologyreseach(Vol.19,pp.111–143).Hauppauge,NY:NOVASciencePublishers.

Poletto,R.,Steibel,J.P.,Siegford,J.M.,&Zanella,A.J.(2006).Effectsofearlyweaningandsocialisolationontheexpressionofglucocorticoidandmineralocorticoidreceptorand11beta-hydroxysteroiddehydroge-nase1and2mRNAsinthefrontalcortexandhippocampusofpiglets.BrainResearch,1067(1),36–42.

Pressman,S.D.,Cohen,S.,Miller,G.E.,Barkin,A.,Rabin,B.S.,&Treanor,J.J.(2005).Loneliness,socialnetworksize,andimmuneresponsetoinfluenzavaccinationincollegefreshmen.HealthPsychol-ogy,24(3),297–306.

Quan,S.F.,Howard,B.V.,Iber,C.,Kiley,J.P.,Nieto,F.J.,O’Connor,G.T.,etal.(1997).TheSleepHeartHealthStudy:Design,rationale,andmethods.Sleep,20(12),1077–1085.

Radloff,L.S.(1977).TheCES–Dscale:Aself-reportdepressionscaleforresearchinthegeneralpopulation.AppliedPsychologicalMeasurement,1(3),385–401.

Rook,K.S.(1984).Promotingsocialbonding:Strategiesforhelpingthelonelyandsociallyisolated.AmericanPsychologist,39(12),1389–1407.Rotenberg,K.(1994).Lonelinessandinterpersonaltrust.JournalofSocialandClinicalPsychology,13(2),152–173.

Routasalo,P.E.,Savikko,N.,Tilvis,R.S.,Strandberg,T.E.,&Pitkala,K.H.(2006).Socialcontactsandtheirrelationshiptolonelinessamongagedpeople:Apopulation-basedstudy.Gerontology,52(3),181–187.Ruan,H.,&Wu,C.F.(2008).Socialinteraction-mediatedlifespanexten-sionofDrosophilaCu/Znsuperoxidedismutasemutants.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica,105(21),7506–7510.

Rudatsikira,E.,Muula,A.S.,Siziya,S.,&Twa-Twa,J.(2007).Suicidalideationandassociatedfactorsamongschool-goingadolescentsinruralUganda.BMCPsychiatry,7,67.

Russell,D.,Peplau,L.A.,&Cutrona,C.E.(1980).TherevisedUCLALonelinessScale:Concurrentanddiscriminantvalidityevidence.Jour-nalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,39(3),472–480.

Russell,D.W.,Cutrona,C.E.,delaMora,A.,&Wallace,R.B.(1997).Lonelinessandnursinghomeadmissionamongruralolderadults.Psy-chologyandAging,12(4),574–589.

Samuelsson,G.,Andersson,L.,&Hagberg,B.(1998).Lonelinessinrelationtosocial,psychologicalandmedicalvariablesovera13-yearperiod:AstudyoftheelderlyinaSwedishruraldistrict.JournalofMentalHealthandAging,4,361–378.

Savikko,N.,Routasalo,P.,Tilvis,R.S.,Strandberg,T.E.,&Pitkala,K.H.(2005).Predictorsandsubjectivecausesoflonelinessinanagedpopu-lation.ArchivesofGerontologyandGeriatrics,41(3),223–233.

Schildcrout,J.S.,&Heagerty,P.J.(2005).Regressionanalysisoflongi-tudinalbinarydatawithtime-dependentenvironmentalcovariates:Biasandefficiency.Biostatistics,6(4),633–652.

Seeman,T.(2000).Healthpromotingeffectsoffriendsandfamilyonhealthoutcomesinolderadults.AmericanJournalofHealthPromotion,14(6),362–370.

Segrin,C.(1999).Socialskills,stressfulevents,andthedevelopmentofpsychosocialproblems.JournalofSocial&ClinicalPsychology,18,14–34.

Shaver,P.R.,&Brennan,K.A.(1991).Measuresofdepressionandloneliness.InJ.P.Robinson,P.R.Shaver,&L.S.Wrightsman(Eds.),Measuresofpersonalityandsocialpsychologicalattitudes:Measuresofsocialpsychologicalattitudes(Vol.1,pp.195–289).SanDiego,CA:AcademicPress.

Spector,W.D.,Katz,S.,Murphy,J.B.,&Fulton,J.B.(1987).Thehierarchical

STRUCTUREANDSPREADOFLONELINESS

relationshipbetweenactivitiesofdailylivingandinstrumentalactivitiesofdailyliving.JournalofChronicDiseases,40,481–490.

Steptoe,A.,Owen,N.,Kunz-Ebrecht,S.R.,&Brydon,L.(2004).Lone-linessandneuroendocrine,cardiovascular,andinflammatorystressre-sponsesinmiddle-agedmenandwomen.Psychoneuroendocrinology,29(5),593–611.

Stranahan,A.M.,Khalil,D.,&Gould,E.(2006).Socialisolationdelaysthepositiveeffectsofrunningonadultneurogenesis.NatureNeuro-science,9(4),526–533.

Sugisawa,H.,Liang,J.,&Liu,X.(1994).Socialnetworks,socialsupport,andmortalityamongolderpeopleinJapan.JournalofGerontology,49(1),S3–S13.

Szabo,G.,&Barabasi,A.L.(2007).Networkeffectsinserviceusage.RetrievedDecember12,2007,from/abs/physics/0611177

991

Tilvis,R.S.,Pitkala,K.H.,Jolkkonen,J.,&Strandberg,T.E.(2000).Socialnetworksanddementia.Lancet,356(9223),77–78.

Wei,P.A.N.(2002).Goodness-of-fittestsforGEEwithcorrelatedbinarydata.ScandinavianJournalofStatistics,29(1),101–110.

Wheeler,L.,Reis,H.,&Nezlek,J.(1983).Loneliness,socialinteraction,andsexroles.JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology,45(4),943–953.

Wilson,R.S.,Krueger,K.R.,Arnold,S.E.,Schneider,J.A.,Kelly,J.F.,Barnes,L.L.,etal.(2007).LonelinessandriskofAlzheimerdisease.ArchivesofGeneralPsychiatry,64(2),234–240.

ReceivedDecember4,2008RevisionreceivedMarch25,2009

AcceptedMarch25,2009Ⅲ

CallforNominations

ThePublicationsandCommunications(P&C)BoardoftheAmericanPsychologicalAssociationhasopenednominationsfortheeditorshipsofExperimentalandClinicalPsychopharmacology,JournalofAbnormalPsychology,JournalofComparativePsychology,JournalofCounselingPsychology,JournalofExperimentalPsychology:General,JournalofExperimentalPsychol-ogy:HumanPerceptionandPerformance,JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology:AttitudesandSocialCognition,PsycCRITIQUES,andRehabilitationPsychologyfortheyears2012–2017.NancyK.Mello,PhD,DavidWatson,PhD,GordonM.Burghardt,PhD,BrentS.Mallinckrodt,PhD,FernandaFerreira,PhD,GlynW.Humphreys,PhD,CharlesM.Judd,PhD,DannyWedding,PhD,andTimothyR.Elliott,PhD,respectively,aretheincumbenteditors.CandidatesshouldbemembersofAPAandshouldbeavailabletostartreceivingmanuscriptsinearly2011toprepareforissuespublishedin2012.PleasenotethattheP&CBoardencouragesparticipationbymembersofunderrepresentedgroupsinthepublicationprocessandwouldpartic-ularlywelcomesuchnominees.Self-nominationsarealsoencouraged.

Searchchairshavebeenappointedasfollows:

●●●●●●

ExperimentalandClinicalPsychopharmacology,WilliamHowell,PhDJournalofAbnormalPsychology,NormanAbeles,PhDJournalofComparativePsychology,JohnDisterhoft,PhDJournalofCounselingPsychology,NeilSchmitt,PhD

JournalofExperimentalPsychology:General,PeterOrnstein,PhD

JournalofExperimentalPsychology:HumanPerceptionandPerformance,LeahLight,PhD

●JournalofPersonalityandSocialPsychology:AttitudesandSocialCognition,JenniferCrocker,PhD

●PsycCRITIQUES,ValerieReyna,PhD

●RehabilitationPsychology,BobFrank,PhD

CandidatesshouldbenominatedbyaccessingAPA’sEditorQuestsiteontheWeb.UsingyourWebbrowser,goto.OntheHomemenuontheleft,find“Guests.”Next,clickonthelink“SubmitaNomination,”enteryournominee’sinformation,andclick“Submit.”Preparedstatementsofonepageorlessinsupportofanomineecanalsobesubmittedbye-mailtoEmnetTesfaye,P&CBoardSearchLiaison,atemnet@apa.org.

DeadlineforacceptingnominationsisJanuary10,2010,whenreviewswillbegin.