The Power of a Note

On my first job as sports editor for the

Montpelier (Ohio) Leader Enterprise, I didn’t get a lot of fan mail, so I was intrigued by a letter that was dropped on my desk one morning.

When I open it, I read:“A nice piece of writing on the Tigers. Keep up the good work.” It was signed by Don Wolfe, the sports editor. Because I was a teenager (being paid the grand total of 15 cents a column inch), his words couldn’t have been more inspiring. I kept the letter in my desk drawer until it got rag-eared. Whenever I doubted I had the right stuff to be a writer, I would re-read Don’s note and feel confident again.

Later, when I got to know him, I learned that Don made a habit of writing a quick,

encouraging word to people in all walks of life. “When I make others feel good about themselves,” he told me, “I feel good too.”

Not surprisingly, he had a body of friends as big as nearby Lake Eire. When he died last year at 75, the paper was flooded with calls and letters from people who had been recipients of his spirit-lifting words.

Over the year, I’ve tried to copy the example of Don and other friends who care enough to write uplifting comments, because I think they are on to something important. In a word too often cold and unresponsive, such notes bring warmth and reassurance. We all need a boost from time to time, and a few lines of praise have been known to turn around a day, even a life.

Why, then, are there so few upbeat note

writers? My guess is that many who shy away from the practice are too self-conscious. They’re afraid they’ll misunderstood, sound sentimental of insincere. Also, writing takes time; it’s far easier to pick up the phone. The drawback with phone calls, of course, is that they don’t last. A note attaches more

importance to our well-wishing. It is a matter of record, and our words can be read more than once, savored and treasured.

Even though note writing may take longer, some pretty busy people do it, including George Bush. Some say he owes much of his success in politics to his ever-ready pen. How? Throughout his career he has followed up virtually every contact with a cordial

response—a compliment, a line of praise or a nod of thanks. His notes go not only to friends and associate, but to casual acquaintances and total strangers—like the surprised person who got a warm pat on the back for lending Bush an umbrella.

Even top corporate managers, who have mostly affected styles of leadership that can be characterized only as tough, cold and aloof, have begun to learn the lesson, and earn the benefits, of writing notes that lift people up. Former Ford chairman Donald Petersen, who is largely credited for turning the company

around in the 1980s, made it a practice to write positive messages to associates every day. “I’d just scribble them along,” he says. “The most important 10 minutes of your day are those you spend doing something to boost the people who work for you.”

“Too often,” he observed, “people we

genuinely like have no idea how we feel about them. Too often we think, I haven’t said anything critical; why do I have to say

something positive? We forget that human beings need positive reinforcement—in fact, we thrive on it!”

What does it take to write letters that lift spirits and warm hearts? Only a willingness to express our appreciation.The most successful practitioners include what I call the four “S’s” of note writing.

第二篇:A Note on the Concept of Relevance

A Note on the Concept of Relevance

Alexander Nicolai

University of Oldenburg

Faculty II:

Computer Science, Economics and Law

Ammerl?nder Heerstra?e 114-118

26129 Oldenburg

Germany

alexander.nicolai@uni-oldenburg.de

David Seidl

University of Munich

Institute of Business Policy and Strategic Management

Ludwigstr. 28

80539 Munich

Germany

seidl@bwl.uni-muenchen.de

Paper submitted to the 3rd Organization Studies Summer Workshop, Crete, 2007

May 27th, 2007

Abstract

Recently there has been a growing concern about a practical irrelevance of the management sciences. Although many researchers talk about ‘relevance’ they hardly ever define what they actually mean by that. We will (a) provide a detailed account of different concepts of

practical relevance, (b) analyse the implicit or explicit expectations concerning relevance that can be found in management science and (c) discuss what expectations concerning relevance appear justified in management science.

Introduction

In recent years there has been a growing concern that the knowledge produced in management science is hardly taken notice of in management practice. This has given rise to urgent calls for making management research more ‘relevant’ and an intensive debate on how to reach this aim has set in (Huff 2000a; Hodgkinson 2001; Rynes et al. 2001; Van de Ven 2001; Wren et al. 1994; Mohrman et al. 2001). While the American Business Schools after the 1950’ies emphasized the importance of academic rigour, the pendulum is now swinging back towards ‘more practical relevance’ (March in Huff 2000). Although many researchers talk about 1

‘relevance’ they hardly ever define what they actually mean by that. In the Oxford Dictionary (1989: 561) we find a very unspecific definition of the adjective ‘relevant’ as ‘[b]earing upon, connected with, pertinent to, the matter in hand’. Thus, the call for more ‘relevance’ as such, says very little about what the relation between management science and management

practice should look like. There are a few studies that distinguish between different types of use of scientific knowledge in management practice (Pelz 1978; Beyer/Trice 1982; Caplan 1983; Astley/Zammuto 1992), however the proposed distinctions remain fairly rough and vague. Apart from that, the literature leaves open the implications of these types of knowledge use for the design of the management sciences.

Against this background, the aim of the proposed paper is threefold: We will (a) provide a more detailed account of different concepts of practical relevance, (b) analyse the implicit or explicit expectations concerning relevance that can be found in management science and (c) discuss to what expectations concerning relevance appear justified in management science.

On the definition of science and practice

For the purpose of this study we will define management science not in terms of a Scientific Community (e.g. Kuhn 1968), i.e. as a particular group of people, but as a specific form of truth-oriented communication that follows particular rules. The scientific journal paper with its peer-review process and its stylistic requirements is the central medium of this

communication (cf. Luhmann 1994). Communication is considered scientific to the extent that its claims are substantiated by reference to theories which themselves are substantiated by reference to yet other theories.

In contrast to management science, management practice can be characterized by its focus on decisions. Accordingly, scientific knowledge is said to be of relevance to management practice if it has some relevance for decision making. This is in line with Luhmann’s conceptualization of practical relevance when he writes:

“Apart from other things, this means that we should analyse the application of scientific results to practice not in terms of action but in terms of decision. It is not a question of whether something that from a scientific point of view has been acknowledged as

correct action is reproduced correctly or not; rather the question is whether the decision 2

situation is modified through the incorporation of scientific result, which may (but doesn’t have to) affect the ultimately selected alternative […] Non-identical

reproduction of scientific knowledge means so much as: change of meaning through change of context, through integration in other neighbourhoods, through initiation of different associations. Whether the injected element is true or untrue is of no direct significance.” (Luhmann1993: 330; our translation)

The particular form of relevance for decision making can vary. For example, scientific knowledge might contribute to defining the decision alternatives, to deciding between the alternatives or to enforcing the decision. If a business school professor acts as a management consultant this – on its own – is not a proof of the practical relevance of science. This is only the case if management practice refers to the network of scientific publications. The same goes for management best-sellers that are widely read amongst practitioners. Even if these publications appear under the label of a scientifically reputable university, it is not enough to prove the practical relevance of science. This is only the case if there are direct or indirect links to the wider network of scientific publication, particularly peer-reviewed scholarly journals.

2. Forms of practical relevance

There are some social scientists who have distinguished between different forms of practical use of scientific knowledge. Rich (1975) distinguished between instrumental utilization (“knowledge for action”) and conceptual utilization (“knowledge for understanding”). Both forms of utilization influence action – the one specifically and direct the other one

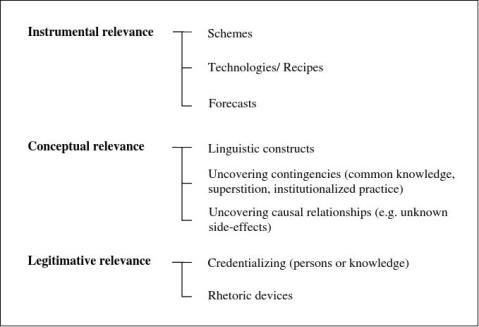

unspecifically and indirect (Beyer/Trice 1982). In addition to that Knorr (1977) and Pelz (1978) introduced the concept of symbolic or legitimative use. Knowledge here is used for legitimating and enforcing decisions. The relevance for the decision maker derives from the fact that the reference to science is relevant for others. This rough differentiation between different forms of utilization can be further differentiated by looking at the particular types of knowledge that is used. Based on an analysis of the literature we can distinguish the following types of knowledge (see Fig. 1):

3

Figure 1: Forms of practical relevance

2.1 Instrumental relevance

(a) Schemes

Schemes provide systematics for ordering decision situations. They are often presented graphically. Examples of such schemes are flow charts, matrixes, typologies or checklists. Schemes help define the alternatives of decision situations but they do not determine the choice between them. For the decision maker schemes are relevant because they help reduce the complexity of the decision situation. In management practice such schemes play an

important role, e.g. the SWOT scheme, the Marketing Mix or the 7-S-Framework. However, most of them were invented by management consultants. Those that actually stem from management science were developed in the early phases of management science, when the scientific discourse in the sense defined above had not been developed, yet. This is, for

example the case with Ansoff’s Product/Market Matrix, which was take up by many strategy scholars but was developed in a practical rather than academic context. The matrix was

originally published in the Harvard Business Review in 1957, a long time before the academic discourse on strategy was developed in the late 1970s. Another example is the typology of strategy by Miles and Snow (1978) which was also developed clearly in a practitioner context, although it is often inadequately referred to as an example of the practical relevance of 4

management science. In view of the modern self-concept of science is not surprising that management science has produced so few practical schemes. While the pre-modern sciences were focussed on the collection, ordering and cataloguing of knowledge (Luhmann, 1994) the modern sciences are focussed on the production of new and often counter-intuitive knowledge. This aspect is missing in schemes.

(b) Technologies and recipes

Technologies and recipes do not only define the decision situation, as schemes do, but they also guide the choice between the alternatives. Examples are the standard strategies of the BCG Matrix, normative if-then statements or success factors. Most authors calling for more relevance of the management sciences probably have technologies and recipes in mind. This is often more implicit in the respective statements. For example, authors often cite

engineering science as ideal for the management sciences or Van de Ven (2000) suggests that a research proposal should contain a “responsible plan […] to implement the findings”. Like the schemes, most technologies and recipes are developed by management consultants. Within the last decade there has been a fierce debate on management fashions which has shown that the technologies and recipes developed by management consultants spread

although – or maybe: because – they do not conform to the criteria of the scientific discourse (Abrahamson 1996; Kieser 1996). Indeed, in scholarly papers one can hardly ever find

something similar. An exception to this are those academic studies that treat “organizational performance” as the dependent variable. Such studies can be found in virtually all areas of management science. To the extent that the independent variables can be controlled by the management the research is considered – according to Schendel (1995) – by definition as relevant for practice. The independent variables can, indeed, be interpreted as setscrews for success; it is this assumed direct applicability that can explain the popularity of such studies (March/Sutton 1997). Yet, if one analyses the sections on “managerial implications” in the performance studies appearing in scholarly journals (e.g. Academy of Management Review, Strategic Management Journal or Journal of Marketing) one can find that the authors are usually very cautious in making any normative claims – if they make them at all. Typical in this respect are the conclusions by Collins and Smith (2006: 557) who established for high-technology firms a positive correlation between commitment-based human resource practices and an organisational climate of trust which ultimately has a positive effect on firm performance:

5

?Our findings suggest that the leaders of high-technology firms should carefully

choose the HR practices used to manage their knowledge workers, because these

practices may shape the firms’ social contexts, which in turn, affect the firms’

ability to create the new knowledge necessary for high performance and growth.”

(Collins and Smith 2006: 557)

In peer-reviewed scholarly journals one can hardly ever find any direct instructions for action and the term “success factor” is seldom used. Indeed, according to March and Sutton (1997) it is almost impossible to deduce such implications from these studies.

A prominent example for a recipe is Porter’s (1980) U-shape and the stuck-in-the-middle hypothesis. The message is: “If you are positioned between cost leadership and

differentiation, you have to move into one or the other direction in order to be successful.” This is clearly a recipe. Yet again, the statement is not really a product of the scientific discourse even though the author is an academic. It was originally presented in Porter’s (1980) popular best-seller Competitive Strategy – without any theoretical or empirical

substantiation. Later it was followed by an academic debate which, however, failed to confirm or disconfirm the underlying hypothesis.

(c) Forecasts

A further form of knowledge with instrumental relevance that has already been pointed out in the classical studies on the philosophy of science (Popper 1957) are forecasts.1 We may think of trends or predictions about the future development of particular markets or of share prices. Knowledge about such developments are directly relevant for the decision maker even though they make no prescriptions as such. For example, knowing whether the share price of a

particular company is going to rise or fall will make a difference to the decision to buy, sell or hold that share. In this sense forecasts are highly relevant to practitioners, since all decisions are based in one way or other on forecasts. Thus, practitioners are often seeking forecasts although they are notoriously unreliable. Barnet et al. (2006) in this sense write: “Forecasting holds endless fascination for people […] Yet, forecasting has also had a record of abject failure.”

Generally forecasts may be based on simple guesses, on intuition, on extrapolations of

patterns observed in the past, or on sophisticated models of calculations. Forecasts to do with managerial topics are mainly a domain of consultants, analysts, market research institutes or We can distinguish forecasts in terms of predictions of concrete events from more general if-then statements in terms of general laws. 1 6

economic research institutes. In the academic literature one usually does not find forecasts, even though academics are often involved in the development of the forecasts. This lack of forecasts in the academic literature might be surprising given that it is still widely assumed that explaining empirical phenomena, i.e. the natural domain of the sciences, and predicting them is based on the same logic of reasoning (Hempel 1963; 1965; Popper 1966): A

phenomenon y is explained by identifying the conditions x that have lead to that phenomenon; hence, when I observe the conditions x I can predict that the phenomenon y will happen. For example, if I have identified the reasons for a particular share price to have risen, I can, whenever I observe these conditions again, predict that the share price will rise again. Yet, such predictions are only possible under “ceteris paribus”, i.e. only if the boundary conditions are held constant. As soon as the boundary conditions change the prediction becomes

inaccurate. Thus, in order to be able to make an accurate prediction one would have to be able to predict also the boundary conditions and the boundary conditions for these boundary conditions. Ultimately, only explanations that would cover the entire universe could be used for making an accurate prediction. Since such explanations are impossible, it is impossible to derive a prediction from the explanation (Bunge 1967; Seifert, 1972; Aligia 2003).

In the social sciences there is a further problem of deriving predictions from explanation which Merton (1957) pointed out: human beings can change their behaviour in reaction to a prediction. As a consequence the prediction may become self-fulfilling or self-destroying. For example, predicting that that the share price of a particular company will rise will motivate share holders to buy the shares which leads to a rise of share prise (self-fulfilling prophecy). Or, predicting that a company will go bankrupt due to a lack of particular competences will lead to the company trying to acquire the competence and thus to evade the predicted fate (self-defeating prophecy).

Due to the described problems forecasts based on sophisticated models turn out to be not much more accurate than those based on na?ve linear extrapolations that anyone can make (Pant/Starbuck 1990). Models having credible face validities make no more accurate forecasts than do ones having poor face validities and simple, crude models tend to forecast more accurately than complex, subtle ones (Barnett et al. 2003: 653). In an analysis of 3142 forecasts about US manufacturing industries during the 1970’s Barnet et al. (2003) found some evidence that the accuracy of predictions depended to a large extent on self-fulfilling prophecies. The exemplary case for this being “Moore’s Law” of 1965 which predicted that the number of components that could be crammed onto a silicon chip would double annually. This prediction which did not really originate in the sciences but was the result of ad hoc 7

speculations has proven surprisingly accurate for the last four decades. This unusual accuracy, as Barnet et al. convincingly showed, was not so much due to the quality of the prediction than a result of the industry members’ believing in the prediction – as a “law” – and making their investments in accordance with it.

We can thus summarize: In contrast to widely held belief, predictions usually cannot directly be derived from explanatory theories. At most such theories can serve as heuristics. Yet, as empirical studies have shown forecasts based on scientific theories tend to be not much more accurate than those based on simple extrapolations. With its inevitable inaccuracy forecasts are not of interest to the scientific community which is interested in certainty and facts.

Against this background it is not surprising that we can hardly find any forecasts in scientific journals or books.

2.2 Conceptual relevance

(a) Linguistic constructs

Particularly since the linguistic turn in the social sciences it has been widely acknowledged that our thinking is deeply influenced by the particular language that we use. Briefly summed up, the most important characteristic of the linguistic turn in the social sciences is the notion that focusing on language acts as a way of structuring or conditioning our ‘access to reality’. Language determines what we perceive as existing (cf. Gergen 1982, p. 101; Rorty 1989; Winch 1958). Our perception is unavaoidably situated in language (Astley 1985). Since the given linguistic categories do not correspond directly to ‘the world out there’ neither do our perceptions of the world correspond to it. In this sense one can say that language to some extent produces a specific reality for us. Whorf explains:

“We dissect nature along the lines laid down by our native languages. The

categories and types that we isolate from the world of phenomena we do not find

there because they stare every observer in the face; on the contrary, the world is

presented in a kaleidoscopic flux of impressions which has to be organized by

our minds – and this means largely by the linguistic system in our minds. We cut

nature up, organize it into concepts, and ascribe significances as we do, largely

because we are parties to an agreement that holds throughout our speech

community and is codified in the patterns of our language.” (Whorf 1956, p.

213)

8

The particular linguistic system – or ‘language game’ (Mauws and Phillips 1995; Wittgenstein 1953) – that is relevant at a particular time and place determines the ways in which the world is conceptualized and experienced; different linguistic systems lead to different conceptualizations and experiences. An often cited example here is the huge number of different categories of snow that the language of the Eskimos contains. Due to that, Eskimos have a different (in particular, a much more differentiated) experience of snow than an average non-Eskimo. On the basis of these particular linguistic categories the Eskimo sees differences in the world where the average non-Eskimo doesn’t (cf. Weick and Westley 1996, p. 446).

Against this background management science can be of practical relevance to the extent that it extends the linguistic constructs used in practice. In management practice we can find many linguistic constructs that came from management science. Amongst these are new concepts (Astley/Zammuto 1991), metaphors (Morgan 1980) or stories (Dyker/Wilkins 1991). One may think about the concept of the “win-win situation” that originated in mathematical game theory that featured later also in practitioner journals (Brandenburg and Nalebuff 1995). Another example is the concept of “heterarchy” which was originally developed by the cyberneticist MacCulloch (1965) as an alternative concept to the hierarchy.

The use of scientific constructs is of practical relevance in the sense that it has the potential of changing the decision maker’s perception of his world and, thus, of his decision situations. Astley and Zammuto in this sense write:

“[New] linguistic constructs and images allow organizational participants to act in

ways that were previously unattended to or inconceivable” (Astley and Zammuto

1992: 450)

A good example from the area of Human Resource Management is provided is by Dubin (1976):

?For example, absenteeism as a symptom can suggest an underlying model that

says explicit behavioral rules, reinforced by appropriate sanctions, amplify

compliant behaviour. A practitioner might, therefore, tighten up the rules

governing absence form work and predict that that would lead to the lowering of

absenteeism. The scientist who is alerted to the problem of absenteeism may

formulate it analytically in different terms as, for example, aspect of the processes

linking individual with organization, with absenteeism being a voluntary break in

the linkage by the individual. The scientist would then analyze the circumstances

9

generating such a condition by focusing on the processes involved. The

practitioner has limited his attention to symptoms, and usually employs a pre-

existing model to indicate how the symptoms should be treated.” (Dubin 1976:

19-20)

An interesting point to note here is that science in this case is relevant to practice not despite but because of its different “language”. Hence a unification of the scientific language and practical language as some authors suggest (e.g. von Krogh/Slocum 1994) would actually destroy the potential for this form of practical relevance.

Generally, one can say that this form of practical relevance fits well together with the basic idea of science if we follow Astley (1985: 511) who sees the “real significance of research

[…] in the opportunity to extend scientific imagination by developing new modes of thinking and interpretation.”

(b) Uncovering contingencies

Organization theorists have studied the different ways in which organizations restrict their scope of possible actions. Amongst these are superstitious learning (Lave/March 1975),

management folklore (Hubbard et al. 1998), executives’ perceptual filters (Starbuck/Milliken 1988) or processes of institutionalisation (Meyer/Rowan 1977). One form of relevance of management science is the uncovering of alternative routes of actions or generally the uncovering of contingencies. This form of knowledge is genuine to the social sciences

(Giddens 1984; Bartunek et al. 2006). As Giddens (1984) noted, one of the central objectives of the social sciences is to uncover underlying social structures together with the restrictions they incur on human behaviour, so that they can be changed. In a survey amongst the board members of the Academy of Management Journal Bartunek et al. (2006: 13), for example, noted that the most important criterion for an interesting scholarly article is that it “challenges established theory; is counterintuitive; goes against folk wisdom or consultant wisdom”. Gergen (1992: 218; cited in Clegg et al. 2004: 32) explicitly evaluates “theory in terms of its challenge the taken-for-granted and its simultaneous capacity to open new departures for action”. A typical example from the area of human resources:

?A sample of 237 agents shows support for the benefits of generalized

investments on agent commitment [i.e., investments in capabilities that people can transfer and deploy to other firms or settings], questioning conventional wisdom

that such investments should be avoided.“ (Charles/ Erin, 2000, p. 1)

10

Similar examples can be found in all areas of the management sciences. In the area of Entrepreneurship, for example, there are studies showing that in contrast to conventional wisdom there is no difference in risk aversion between owners and managers (Brockhaus 1980) and in Strategic Management, for example, there are studies (Martin/Sayrak, 2003) showing that diversified companies do not necessarily face a “conglomerate discount” as widely assumed. A more generalised sensitivity for contingencies is created by all those studies that lead to a deeper understanding why possibilities for action are blinded out. A good example for this are the neoinstitutional studies which have shown how societal institutions affect our awareness for potential courses of action (Zucker 1977; Powell and DiMaggio 1991).

Sometimes academic knowledge that at first sight appears to be of instrumental relevance turns out to be more conceptually relevant by raising the awareness for contingencies. A good example for this is game theory which has often been cited as a prime example for providing instrumentally relevant knowledge. When Neumann and Morgenstern published Theory of Games and Economic Behaviour in 1944 it was hailed as possessing a high degree of prescriptive potential. With the help of the theory, it was assumed, one could calculate the best move in interdependent decision situations. At the beginning of the 1990’s game theory became popular in the discipline of Strategic Management (Saloner 1991) and consulting firms like McKinsey proclaimed: “game theory is hot” (Barnett cited after

Berninghaus/V?lker 1997). Concerning questions like “market entry: yes or no?” game theory was assumed to provide an answer. Game theory was presented as instrumentally relevant knowledge in the form of a technology. Indeed, the paper by Brandenburg and Nalebuff (1995) in the Harvard Business Review on “The Right Game: Use Game Theory to Shape Strategy” was widely considered as one of few exemplars for the instrumental relevance of science. This paper had strong repercussions in management practice. Yet, in the paper there are neither models nor suggestions for calculating optimal strategies, nor any other kind of instrumental knowledge.2 Instead of any instrumental knowledge the paper provided on the one hand linguistic artefacts like “value net” or “coopetition”. On the other hand the paper also showed how game theory is useful for uncovering contingencies. By calculating the “added value” the authors, for example, showed that in particular constellations of actors and 2 Game theory is often seen a “tool” which helps to deduce the best decision. Critics, however, object that game theory can be used to rationalize anything. According to the "folk theorem" any outcome in the range from total cooperation to total defection is possible in the repeated prisoner's dilemma. See for a discussion Postrel (1991). In the early 1990s some strategy researchers viewed game theory as one of the most promising candidates for future research. Today, this optimism seems to be gone. In the recent volumes of the Strategic Management Journal, for example, we did not find articles on game theory any more.

11

interests it is advantageous to reduce the total value of the earnings that are to be distributed, in order to increase individual earnings. In this way the paper points out options for action which the practitioner usually would not have seen. In the cited example a producer of video games can increase his revenues by selling fewer game sets than the market would have taken.

These examples demonstrate that science can prove relevant to practice if it points out

specific contingencies. Beyond that one may argue that the scepticism inherent in scientific discourse can generally, independently of the concrete example of application, contribute to the uncovering of contingencies. In other words, the scientific discourse might induce into practice a useful scepticism vis-à-vis taken-for-granted assumptions.

(c) Uncovering causal relationships

A further form of conceptual relevance consists in the uncovering of causal relationships and unknown side-effects. There are numerous examples where scientific research has lead to awareness amongst practitioners for causal relationships that had not been noticed before. Good examples for this are the studies that have shown the counterproductive effects of performance based incentives (e.g. Osterloh/Frey 2006; Frey/Jegen 2001; Frey/Osterloh 2005). While it had been widely accepted that the performance of managers could be

increased through performance related pay, Frey and his colleagues demonstrated that such measures can lead to a “crowding out” of the managers’ intrinsic motivation. Hence, in those cases where managers were originally intrinsically motivated the introductions of

performance based payment could have a negative effect on the managers’ performance. Frey and Jegen write:

“Motivation Crowding Theory serves as a warning against rash generalizations of

conclusions derived from simple task environments […], where intrinsic

motivation can be assumed to play no role, and therefore the crowding-out effect

cannot occur.” (Frey and Jegen 2001: 596)

Another, classical example is Argyris’ (1964) study on the paradoxical effects of monitoring and control: strict control has a negative effect on the loyalty of employees to their firms. Hence, the very control measures produce the adverse behaviour it tries to control. Thus, the study uncovered an underlying causal relationship between control and corporate behaviour that hadn’t been understood in this way before.

Another example of an academic study that proved practically relevant by uncovering causal relationships is by Phillips and Zuckerman (2001). Based on a large set of empirical data they 12

showed a strong correlation between analysts’ social status and their share ratings. Compared to their high-rank and low-rank colleagues, middle status analysts are particularly unlikely to issue sell recommendations.

For the decision maker such academic studies are of relevance in that they can provide a better understanding of the decision situation. Similarly to the other forms of conceptual relevance the uncovering of causal relations tends to increase the complexity of the decision situation by pointing out new connections: In the first two examples the decision situation is made more complex by pointing out counterproductive side-effects and in the third example the decision situation is made more complex by pointing out the unreliability of information that is used as a basis for decision making.

2.3 Legitimative Relevance

(a) Credentializing

Whitley (1988) is sceptical about the possibilities of applying results from the management sciences to practice in any straight-forward way. He writes:

?[A]ttemps to establish a general ‘science of managing’ which would generate

knowledge of highly general relations between limited and standard properties of

separate, standard objects are doomed to failure since ‘managing’ is not a standardized activity.” (Whitley 1988: 64)

Instead he emphasises a form of legitimative relevance of scientific knowledge that he terms credentializing. The objects of credentializing can be graduates from business schools who receive a certificate or degree. But also particular knowledge domains can be credentialized with the help of academic knowledge. Credentializing is similar to that which is often referred to as “symbolic use” (Pelz 1978):

?If information serves to confirm the decision maker’s own judgment of the situation, we have a conceptual use. If the evidence helps him to justify his position to someone else, such as a legislative committee or a public group [or a company’s shareholders], the use is symbolic.” (Pelz 1978: 352)

As Whitley (1985) amongst others has shown, academic credentials are of particular

importance in various domains of management practice. One may for example also think of how the burgeoning literature on the strategic role of middle managers has strengthened their position in management practice.

13

Credentializing doesn’t necessarily imply that scientific knowledge is used in any ?improper“ or arbitrary way (Pelz 1978, p. 352). For example, business schools that select and train

students can serve the function of a talent filter (Arrow 1973). Degrees from business schools certify the talent. Scientific research influences the curricula of Business Schools and in a complex way controls certification. In this way, scientific knowledge provides management practice with a non-arbitrary measurement for assessing competence (Whitley, 1995: 63). Credentializing can refer to people but also to specific domains of knowledge. Knights and Morgan (1994), for example, argue that the increasing relevance of the discipline Business Policy / Strategic Management goes hand in hand with the emergence of public corporations during the last hundred years. The large modern companies are characterized by a division of ownership and control (Bearle and Means 1932). While the owner-managers of the older

times could legitimate their decisions with their ownership, the employed managers are forced to revert to their competences as a source of legitimation. Consequently, new sources of legitimation of a company’s “big decisions” became necessary. According to Knights and Morgan the academic discourse of Strategic Management filled this vacuum. Another

example for this is the field of Accounting. The professionally organized skills in accounting faced a serious legitimacy crisis in the 1970’s. Reasons for this were the high inflation rates and legal challenges. According to Whitely (1995: 63) this resulted in a demand for ?valid knowledge“ and ?general skills“. This lead to a scientification of Accounting:

?The introduction of statistical and mathematical techniques into accounting and finance training programmes […] buttressed the scientific appearance of accounting skills, even if they are rarely utilized in practice. Thus, the desire of accounting academic to become ‘scientific’ and academically respectable in the U.S.A. matched the growing need for ‘scientific’ foundations and legitimacy for accounting practitioners and accounting skills.” (Whitely, 1995, p. 63)

From this we may distinguish a somewhat different form of credentializing that Sturdy et al. (2006) pointed out: legitimating people or domains of knowledge towards themselves. Sturdy et al. showed how academic degrees strengthened the self-confidence of managers and in this way increased their ability to act. Scientific knowledge in this way serves to justify the own position to oneself. This is also a form of practical relevance.

(b) Rhetoric devices

14

A second form of legitimative relevance is the use of scientifically generated knowledge as rhetoric devices. This form of practical relevance of the sciences has been widely noted in the literature. Astley and Zammuto (1992) for example speak of the relevance of symbolic labels. This form of relevance might sound very similar to that of linguistic constructs. Yet, the particular function that the scientific knowledge plays in both cases is very different. While scientific knowledge used as linguistic construct serves to enlarge the practitioners

understanding of his or her problem situation, used as rhetoric device it serves to legitimate the particular choice of alternatives. Couching one’s arguments in scientific language often increases the perceived legitimacy of the argument. Examples for the rhetoric use of scientific labels in practice abound. For example, the concept of the “win-win situation” that we described already above is often used as a scientific label – independently of its concrete meaning – to justify the chosen alternative. Astley and Zammuto write:

“Symbolic utilization is the use of information from the scientific realm to

legitimate managerial decisions, actions, or ideas. For example, managers often

point to theoretical models or research findings to justify course of action” (Astley and Zammuto 1991: 452)

While such rhetoric use is often criticised as “improper” use of scientific knowledge others have pointed out the value of such use. Conger (1991), for example, argued that rhetorical techniques serve an important leadership function:

“Rhetorical techniques of metaphors, of stories, of repetition and rhythm, and of

frames all help to convey ideas in the most powerful ways. They ensure that

strategic goals are well understood, that they are convincing, and that they spark

excitement. If you as a leader can make an appealing dream seem like tomorrow’s reality, your subordinates will freely choose to follow.” (Conger 1991: 44)

As Brunsson (1981; 2003) and others have convincingly argued, “irrational” techniques such as rhetorical use of language are often necessary requirements for organizational action. In this sense science can be of very practical relevance.

3. Discussion: Which relevance claims seem justified?

After distinguishing the different notions of practical relevance we will discuss which types of relevance claims can be justified. For this purpose we have developed several test criteria: 15

(1) To what extent does the particular form of relevance imply a trade-off between scientific rigour and practical relevance:

The relation between scientific rigour and practical relevance has variously been described in the literature. While some people see no problem in combining rigour and relevance of

academic research (e.g. Gibbons et al. 1994) others again claim – often on logical grounds –a trade-off between the two (e.g. Mayer 1993; Lampel and Shapira 1995; Nicolai 2004). Yet, most authors discuss this issue based on a very vague notion of relevance. Our taxonomy of different forms of relevance allows us a somewhat more nuanced discussion. In the following we want to discuss this relation for each form of relevance. In line with our general

characterization of science as a particular form of truth-oriented communication we would characterise research as scientifically rigorous to the extent that it is integrated into the network of other scientific communication. This in particular means that knowledge claims are substantiated with reference to theories that are themselves substantiated with reference to other theories.

Our discussion of the different forms of practical relevance has already shown that some

forms of instrumental relevance do not sit very well with scientific rigour. Yet, there are some differences between the different forms of instrumental relevance. In the case of schemes the relation is a somewhat neutral one. While the development of schemes does not directly contradict scientific reasoning as such it will never be the direct objective of a scientific research project given that the suggestion of schemes as simple ordering devices is of no particular scientific value. If at all, such schemes will only be a by-product of scientific research. The case is somewhat different for technologies where we tend to have a direct trade-off. Technological claims cannot be related to scientific theories as would be expected of a scientifically rigorous communication. Usually they can neither be directly derived from theories nor can they be directly substantiated by them since the theories tend to be too

general for any specific, concrete technologies (Bunge 1967; Zelewski 1995; Nienhüser 1989; Jarzabkowski and Wilson 2006). At most, theories serve as heuristics for the development of theories (Kirsch et al. 2007). The same goes for predictions as we elaborated already above. Apart from that one may generally question, whether management sciences are able to

produce technologies at all without having to give up their claim for rigour. Whitley (1995), for example, argues that management isn’t a task that can be standardized. Consequently, standardized solutions like technologies make no sense in management. Developing

management technologies, thus, implies a kind of ignorance. Only by ignoring differences e.g. 16

between companies from different industries, countries, life cycles etc. can one propagate general technologies. If this is true there is a trade-off between instrumental relevance and scientific rigour. Indeed, in the course of their academization management sciences tend to become less instrumental. Particularly at the academic top-tier one can hardly find any

technologies. On the other side, popular management best-sellers that do not meet scientific standards are often written in the recipe manner of a cook book. In contrast to that, the different forms of conceptual relevance seem not to imply such a trade-off. Relevance that results from a deeper understanding of the practical situation appears not to contradict a notion of science as a particular form of truth-oriented communication.

The relation between scientific rigour and the various forms of legitimative relevance is somewhat different again. Initially, scientific rigour and legitimative relevance go very well together. The more rigorous, i.e. the more scientific, a particular knowledge claim is

considered the better it can be used to provide credentials and the better they can be referred to in order to legitimate something rhetorically (Kieser 2002). Yet, as will be discussed in the following section, in consideration of theory pluralism the relation between rigour and legitmation becomes more ambivalent.

(2) To what extent does the particular form of relevance fit together with the pluralism of theories in management science?

Management science is a “fragemented adhocracy” (Whitley 1984) characterized by a pluralism of theories. Often scientific statements contradict each other without necessarily being wrong. The entire field of management studies is characterized by a plurality of

incommensurate paradigms. Scientific reasoning within the social sciences does not lead to a resolution of this situation. Attempts at solving this problem result in a ?Münchausen-Trilemma“, i.e. in an infinite regress, a logical circle, or just in dogmatism (Albert, 1985;

Scherer/Dowling, 1995; Scherer, 1999). Paradigms and theories do not converge in the course of the scientific evolution – the pluralism of theories is resistant.

Theoretical pluralism is a problem to instrumental relevance. If different theories are associated with different instrumental claims they neutralize each other. Instrumental relevance is based on the reduction of complexity, i.e. on the exclusion of decision

alternatives. This is most obvious in the case of instruments that suggest a “one best way”. Yet, theoretical pluralism re-establishes the complexity for the decision maker. Thus, with increasing pluralism instrumental relevance is reduced. Since science itself doesn’t offer any 17

procedures for choosing between the instruments, this problem cannot be solved with scientific means.

The consequences of theoretical pluralism for conceptual relevance are different. Conceptual knowledge can also contradict each other. Yet, since conceptual relevance is not restricted on the “output” of the research but on the process of scientific reasoning itself, the different

scientific statements stand in a kind of dialectical relation to each other. Theoretical pluralism, in this sense, can lead to an increasing conceptual relevance as Astley und Zammuto demonstrate:

“Problem-solving skills can be increased by developing what Bartunek et al

(1983) refer to as ‘complicated understanding’ – the ability to see and understand

organizational events from several, rather than single, perspectives. Complicated

understandings are important because many of the problems managers face – such as motivating employees, formulating strategies, etc. – are complex or ‘wicked’

problems (Rittel and Weber 1973), which can be framed in many different ways,

have many different answers, and are rarely definitely resolved.” (Astley and

Zammuto 1991: 455)

The legitimative relevance of management science, at first, is increased by theoretical

pluralism. Due to the pluralism of management theories it is possible to find a legitimation for almost any form of management practice (Beck/Bon? 1989, Nicolai 2004). The fragmentation of the management sciences makes it possible to pick out individual elements of scientific communication in order to use them opportunistically in practical communication. In the long run, however, theoretical pluralism undermines legitimative relevance. To the extent that scientific justifications in management practice appear arbitrary legitimation disappears. This is reinforced by a process that can be called ?reflexive scientification“ (Beck/Bon?, 1989) of management practice. Practitioners no longer view results of scientific research like “theory-less natives” view the missionary. Particularly larger organizations have rich experience in the contact with science. They know, at least implicitly, about the standard shortcomings of

research in the social sciences and, thus, about the possibility of things being different. This is another reasons why many people have observed an increasing erosion of scientific authority (Luhmann, 1994, p. 629). In so far theoretical pluralism reduces the legitimative relevance of the management sciences in the long run.

(3) To what extent does the particular form of relevance presuppose that the practitioners understand the scientific context in which the knowledge was developed?

18

Given the fact that management science and management practice operate according to different logics (Luhmann 1998; Astley /Zammuto 1992; Seidl 2007; Nicolai 2003) an important question is whether the particular knowledge generated in management science requires the practitioners to understand the scientific context in order for the knowledge to prove relevant to them. Again, there are great differences between the different forms of relevance. The three types of instrumental knowledge typically require no understanding of the larger context within which the knowledge was developed. This is already implied by the concept of “instrument”; in order to use an instrument one just needs to know under what conditions it is to be used and what effect it has – one need not understand why the instrument works. This is true for schemes and forecasts but also for techniques. For Luhmann (1993: 328) the possibility of a context-free transferral is the defining characteristic of a technique. Luhmann in this sense writes:

“The application of scientific knowledge becomes highly technical whenever it

can be practiced without an understanding of the theoretical context of origin.”

(Luhmann 1993: 329; our translation)

In line with this, the texts in which schemas, techniques and forecasts are presented usually provide very little in terms of theoretical explanations. Instead, they offer guidelines on the application of the instrumental knowledge. Typically, these texts constitute a one-way communication. The author presents the instrumental knowledge and does not expect any questioning.

In the case of conceptual forms of knowledge the situation is very different. They usually require – at least rudimentary – understanding of the theoretical context in which the knowledge is embedded (cf. Luhmann 2005). Without that context the meaning of the

knowledge forms cannot be grasped. In contrast to instrumental knowledge where it is enough to understand how to use the knowledge, the central characteristic of conceptual forms of knowledge is the widening of our understanding. Typically, the user of that knowledge will have to work with it in order to “build” it into his/her concrete experience. For example, in order to apply the linguistic concept of the “win-win situation” to a concrete decision situation the reader needs to understand the basic ideas of game theory. This is even more so in the case of the other two forms of conceptual relevance, i.e. uncovering contingencies and causal relationships. In order to understand the counterproductive effect of incentives one needs to understand motivational theory. In line with this, the linking to the wider theoretical contexts 19

is usually a central part of the texts presenting conceptual forms of knowledge. Typically, these texts are written in a dialogical form, inviting the reader to question the argument. All this puts some strain on the practitioner trying to use conceptual forms of knowledge. It requires him or her to engage in scientific forms of thinking and communication. Conceptual knowledge can, thus, only diffuse into practice if the practitioners are able and willing to acquire some (at least basic) knowledge of the theoretical background. Luhmann (1993: 332) in this sense writes that in order for such knowledge to diffuse into practice on a larger scale we need a scientification of practice – something that can already be observed (e.g. Whitley 1995).

However, all this cannot guarantee that the scientific knowledge is picked up “correctly”. On the contrary, a lot of writers (e.g. Astley and Zammuto 1991; Seidl 2007; Luhmann 1993) have argued that scientific knowledge is often misunderstood by practice. Yet, as the same authors have also pointed out such misunderstandings can still be very productive and in this way still prove of relevance to practice. But since such misunderstandings are not without dangers it is nevertheless necessary to try encouraging “correct” understanding.

Finally, for legitimative forms of relevance an understanding of the wider theoretical context is usually unnecessary. In some cases this could even be counter-productive. One may only think of opportunistic uses of rhetoric devices, which would be seen through if the receiver of the communication understood too much of the theoretical background.

(4) To what extent can the different forms of relevance be combined?

Finally we want to discuss briefly the extent to which the different forms of relevance go together or contradict each other. Pelz (1978: 352) already touched on this question when he pointed out that there was “some shading” between the different forms of relevance. Yet, the relation between the forms of relevance seems to be more complex. We will start with the relation between instrumental and conceptual forms of knowledge. Pelz argued that instrumental use can go very well with conceptual use. He explains:

“If the evidence persuades a decision maker to adopt option A rather than B, the

use is clearly instrumental. If he has already adopted option B, however, and the

evidence reinforces his belief in this option, the use is more properly called

conceptual.” (Pelz 1978: 352)

In contrast to Pelz, however, we would argue that there usually will be a trade-off between instrumental and conceptual forms of relevance. As we showed above, instrumental 20

knowledge serves to simplify decision situations helping to reach a decision. It, thus, reduces the complexity of the decision situation. Conceptual knowledge, in contrast, tends to open up the decision situation increasing the complexity (Astley and Zammuto 1991: 455). In other words, instrumental forms of knowledge lead to equivocality reduction while conceptual forms increase equivocality.

The relation between instrumental forms and legitimative forms is somewhat more

complicated: Instrumental knowledge can very well serve legitimative purposes if it fits the specific situation. However, the instrumental qualities of knowledge are the better the easier to understand and the more precise it is. With the ease of understanding and its precision, however, the scope of potential legitimative use is reduced, since the addressees of the

communication can easily see though “improper” reference to the knowledge for legitimtive purposes.

Finally, conceptual and legitimative relevance appear to go together fairly well. The complexity of conceptual forms of knowledge and the requirement to understand the wider context make it easier to use such form of knowledge for legitimative purposes. The complexity provides flexibility and the requirement to understand the context prevents the addressees of the communication to see through “improper” use.

4. Conclusion

After having analysed the different forms of relevance against the background of our four test criteria we can now summarize what implications this has for the justification of any

relevance claims. Our first and second test criterion led to the result that instrumental forms of relevance appear to stand in conflict with the logic of management science. In contrast to that, conceptual relevance –and to some extent also legitimative relevance – go well with it. Yet, the third test criterion conveyed that while instrumental and legitimative knowledge can be applied by practitioners fairly easily, the use of conceptual knowledge is quite demanding requiring the practitioner to understand the wider theoretical context. Finally, we saw that while conceptual and legitimative relevance go together fairly well, it is less so for the other combinations. We thus reach the following conclusion:

1. Management science cannot be expected to produce instrumentally relevant

knowledge (cf. Astley/Zammuto 1991: 452) as it conflicts with the logic of science. 21

2. Instead, management science can be expected to provide conceptually relevant knowledge as this accords with the very logic of management science.

3. As a side product management science can also provide legitimative forms of

knowledge as this goes well with the production of conceptual forms of knowledge. Management science cannot focus directly on the production of legitimative forms of knowledge as it would undermine the scientific endeavour and ultimately the legitimative form of relevance itself.

4. Yet, this form of practical knowledge is very demanding for both academics and practitioners. Practically relevant science does not reach the practitioner as a “deliverable”, ready for consumption. Practitioners have to be able and willing to engage with the theory even if the academic knowledge may question their current theories in use and even if it is not directly applicable. Academics, in turn, have to accept that scientific knowledge is not generally superior to practitioners’ knowledge. Instead, application is a learning process for both sides.

22

References

Albert, Hans (1985): Treatise on critical reason, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Aligia, P.D. (2003) “Prediction, explanation and the epistemology of future studies”. Futures

35: 1027-1040.

Ansoff, I. (1957) Strategies for Diversification, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 35 Issue 5,

Sep-Oct 1957, pp.113-124

Argyris, Ch. (1964) Integrating the individual and the organization. New York: Wiley.

Arrow, Kenneth J. (1973): Higher Education as Filter, in: Journal of Public Economics, Vol.

2, pp. 193-216

Astley, W.G. (1985): Administrative science as socially constructed truth, in: Administrative

Science Quarterly, Vol. 30, pp. 497-513

Bartuneck, J. M., Gordon, J.R. and Weathersby, R. P. (1983) “Developing ‘complicated’

understandings in Administrators” Academy of Management Review 8: 273-284.

Beck, Ulrich/ Bon?, Wolfgang: Verwissenschaftlichung ohne Aufkl?rung?, in: dies. (Hrsg.):

Weder Sozialtechnologie noch Aufkl?rung? – Analysen zur Verwendung

sozialwissenschaftlicher Wissens, Frankfurt a.M., 1989, S. 7-45

Beyer, J.M./ Trice, H.M. (1982): The utilization process: A conceptual framework and

synthesis of empirical findings, in: Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 27, pp. 591-622.

Brockhaus, R. H. (1980): Risk Taking Propensity of Entrepreneurs. In: Academy of

Management Journal, 23,. 1980, S. 509-520.

Bruno S. Frey and Margit Osterloh, 'Yes, managers should be paid like bureaucrats', Journal

of Management Inquiry, No. 1, 14 (2005) 96-111

Brunsson, N. (1982) “The irrationality of action and action rationality: Decisions, ideologies

and organizational actions”. Journal of Management Studies 19: 29-44

Brunsson, N. (2003) The Organization of Hypocrisy: Talk, Decisions and Actions in

Organizations. Copenhagen Business School Press; 2Rev Ed edition.

Bunge, M. (1967) Scientific Research. Berlin: Springer

Caplan, N. (1983): Knoledge Conversion and Utilization, in: Holzner, B. (Ed..): Realizing

social science knowledge, Wien/Würzburg: Physica, pp. 255-264

23

Collins, ?? and Smith, ??? (2006) …

Conger, J. (1991) “Inspiring others: the language of leadership” Academy of Management

Executive 5: 31-45

Dyer, W.g./ , Wilkins, A.L. Jr. (1991): Better Stories, Not Better Constructs, to Generate

Better Theory: A Rejoinder to Eisenhardt, in: Academy of Management Review, Vol. 16, No. 3 , pp. 613-619

Fiskel, J. (1980): Winning is not everything: The midlife crises of Operations Research, in:

Interfaces, Vol. 10. No. 2, Pp. 106-107.

Frey, B. and Jegen, R. (2001) “Motivation crowding theory: a survey of empirical evidence””

Journal of economic surveys 15: 589-611

Giddens, A. (1984) The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hempel, C. (1963) “Explanation and prediction by covering laws” in Baumin, B. (ed.)

Philosophy of science: The Delaware Seminar, New York: Wiley

Hempel, Carl (1965) Aspects of scientific explanation. And other essays in the philosophy of

science. New York: Free Press.

Hubbard, Raymond/ Vetter, Daniel E./ Little, Eldon L.: Replication in Strategic Management:

Scientific Testing for Validity, Generalizability, and Usefulness, in: Strategic

Management Journal, Vol. 19/ 1998, S. 243-254

Jarzabkowski, P. and Wilson, D. (2006) “Actionable strategy knowledge: A practice

perspective” European Management Journal 24: 348-367

Kirsch, W., Seidl, D. and van Aaken, D. (2007) Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung:

Grundlagenfragen und Anwendungsorientierung. Stuttgart: Sch?ffer-Poeschel.

Knigths, D./Morgan, G. (1991), Corporate Strategy, Organizations, and Subjectivity: A

Critique, in: Organisation Studies, 12. Jg., S. 251-273.

Krogh, G. von, Roos, J. and Slocum, K. (1994). ‘An Essay on Coporate Epistemology’.

Strategic Management Journal, 15, 53-71

Lampel, J. and Shapira, Z (1995) “Progress and its discontents: Data scarcity and the limits of

falsification in Strategic Management” Advances in Strategic Management 12: 113-150. Lave, C./ March, J. (1975): An Introduction to Models in the Social Sciences, New York:

Harper and Row.

24

Luhmann, N. (1993) Theoretische und praktische Probleme der anwendungsbezogenen

Sozialwissenschaften”. In Luhmann. N. Soziologische Aufkl?rung 3: Soziales System, Gesellschaft, Organisation. Opladen: Westdeutscher verlag, pp. 321-334.

Luhmann, N. (1994): Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft. 2nd ed.., Frankfurt am Main 1994. Luhmann, N. (2005) ?Communication barriers in management consulting“ in Seidl, D. and

Becker, K.H. (eds.) Niklas Luhmann and organization studies. Copenhagen:

Copenhagen Business School Press.

Luhmann, Niklas: Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft, Frankfurt a.M., 2. Aufl., 1994 Margit Osterloh and Bruno S. Frey, 'Corporate Governance for Crooks? The Case for

Corporate Virtue', in: Anna Grandori (eds.) Corporate Governance and Firm

Organization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006): 191-211.

Martin, J.D./ Sayrak, A. (2003): Corporate Diversification and Shareholder Value: a survey of

recent literature, in: Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 9. p. 37-57

Mayer, T. (1993) Truth versus precision in economics. Aldershot: Edward Elgar

McCulloch, Warren S. (1965). Embodiments of Mind. Cambridge.

Merton, R. (1957) Social Theory and Social Structure. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Meyer, J. W./ Rowan, B. (1977): Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth

and Ceremony, in: in: American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 83, No. 2, p. 340-363) Mohrman, S.A./ Gibson, C.B./ Mohrman, A.M. (2001): Doing Research that is useful for

practice: A model and empirical exploration, in: Academy of Management Journal 44, No. 2, pp. 357-375

Neumann, J. von, Morgenstern, O. (1944): Theory of Games and Economic Behavior.

University Press, Princeton NJ

Nienhüser, W. (1989) Die praktische Nutzung theoretischer Erkenntnisse in der

Betriebswirtschaftslehre. Probleme der Entwicklung und Prüfung technologischer Aussagen, Stuttgart 1989

Pant, P.N. and starbuck, H.W. (1990) ?Innocents in the forest: forecasting and research

methods“. Journal of Management 16: 433-460.

25

Pelz, D.C. (1978): Some Expanded Perspectives on Use of Social Science in Public Policy, in:

Yinger, J.M./ Cutler, S. J. (eds.) Major Social Issues – A Multidisciplinary View, New York/London, 346-357

Popper, K. (1957) The Poverty of historicism. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

Popper, K. (1966) Logik der Forschung.

Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and

Competitors, New York: Free Press

Postrel, S. (1991): Burning Your Britches Behind You: Can Policy Scholars Bank an Game

Theory?, In Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, p153-155

Schendel, D. (1995): Notes from the Editor-in-Chief. In: Strategic Management Journal, 16.

Jg. (1995), S. 1-2.

Scherer, Andreas Georg/ Dowling, Michael J.: Towards a Reconciliation of the Theory-

Pluralism in Strategic Management – Incommensurability and the Constructivist

Approach of the Erlangen School, in: Advances in Strategic Management, Vol. 12A/ 1995, S. 195-247

Scherer, Andreas Georg/ Steinmann, Horst: Some Remarks on the Problem of

Incommensurability in Organization Studies, In: Organization Studies, Vol. 20, p. 519-544

Seifert, H. (1972) Einführung in die Wissenschaftstheorie. München: Beck.

Starbuck, W.H. / Barnett, L./ Narayan, P. Which dreams com true? Endogeneity, Industry

Structure, and Forecasting Accuracy, in Starbuck, W.H. (2006): Organizational Realities – Studies of Strategizing and Organizing, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 509-566 Starbuck, W.H./ Milliken, F.J. (1988): Executives perceptual filters: what they notice and they

make sense. In Hambrick, D. (ed.) The Executive Effect: Concepts and Methods for Studying Top Managers, Greenwich: JAI Press, pp. 35-65

Van de Ven, A. (2000): Professional science for a professional school – Action science and

normal science, in: Beer, M./ Nohria, N. (Eds.): Breaking the Code of Change, Boston (Ma.): Harvard Business School Press, pp. 391-446

Weick, K.E. (1993): Organizational redesign as improvisation, in: Huber, G.P./Glick W.H.

(Eds.): Organizational Chance and redesign: Ideas and insights for improving

performance, New York: Oxford Press, p. 346-382

26

Whitley, R. (1988): The Management Sciences and Management Skills, in: Organization

Studies, Vol. 9, pp. 47-68

Whitley, R. (1995): Academic Knowledge and Work Jurisdiction in Management, in:

Organization Studies, Vol. 16, pp. 81-105

Whitley, Richard: The Fragmented State of Management Studies: Reasons and Consequences,

in: Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 21/ 1984, No. 3, S. 331-348

Zelewski, S. (1995), Zur Wiederbelebung des Konzepts technologischer Transformationen im

Rahmen produktionswissenschaftlicher Handlungsempfehlungen, in: W?chter, H.

(Hrsg., 1995), S. 89-124.

Zucker, L. G. (1977): The Role of Institutionalization in Cultural Persistence, in: American

Sociological Review 42, S. 726-743.

27