例1:

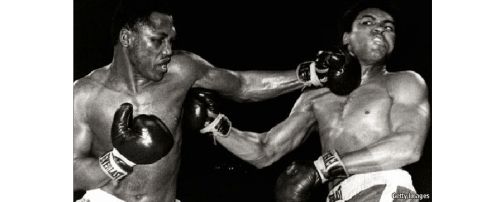

Joe Frazier

“Smokin Joe” Frazier, heavyweight boxer, died on November 7th, aged 67 ?

?

TO SAY that Joe Frazier had a left hook was like saying the Tomcat jet fighter is an aeroplane. This one was devastating. You knew it was there, but he kept it hidden. For most of a fight he would press in, head down like a bull charging, fists close to the chest. He was short for a heavyweight, five feet eleven, and made himself look shorter, hunching his shoulders and punching close with his stumpy, jabbing arms. He didn't dance around, but worked away at it, bobbing and weaving relentlessly, throwing away perhaps two punches for every one he

landed. His style was to keep aggressively on, wear a man down, get him winded. Then—boom!—the dazzling left hook that sent his opponent sprawling.

His craft had been honed for years. First on the heavy bag he'd made himself that hung from the oak tree in the yard of the family shack in Beaufort, South Carolina: just an old burlap bag stuffed with rags and corn cobs, Spanish moss and rocks. Anything that could take a punch. His mamma whupped him with a braided vine and his daddy whupped him with a belt when he deserved it, and then he'd pummel that bag. His uncle had told him at eight years old, as he watched the “Wednesday Night Fight” on the blurry black-and-white TV with the other men,

that he could be another Joe Louis. He aimed to do it. Later he practised on the hanging sides of beef at Cross Brothers' slaughterhouse in Philadelphia, Rocky Balboa in real life. One, two in the refrigerated room, breath smoking, gloves smoking. That was what his first trainer told him to do when he signed on at the police gym in 1961: make his gloves smoke.

Out of 37 professional fights, he won 27 with knockouts. His left hook won him gold at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, toppling Hans Huber, even though his left thumb was so hurt it was probably broken. It earned him the world heavyweight crown, besting Jimmy Ellis in the fifth at Madison Square Garden in 1970. And

most spectacularly it was how he beat Muhammad Ali in “The Fight of the Century” at the Garden in 1971, when after 14 rounds of increasing ferocity (just throw punches, he was thinking. Just throw punches) he landed a blow on that bragging jaw that won him the fight on points and sent Ali round to the hospital.

Nothing was sweeter to him than that one punch. He kept a photo of it, blown up huge, in the office of the gym where he had trained in Philadelphia and later

trained young boxers himself. His rivalry with Ali was the most intense in boxing. It may have thawed at moments, but deep down he hated him. Hated the big mouth that called him ugly, flat-footed and a gorilla (punching a little rubber

gorilla as he said it, contemptuously), while Frazier would sit with his plain, solid, patient face wondering whether he could get one word in. Especially he hated Ali calling him an Uncle Tom, a white man's black boxer.

Ali had been stripped of his world heavyweight title in 1967 for refusing the Vietnam draft. That made some whites go to Frazier's corner, and made many blacks go on calling Ali champion even when Frazier was. That hurt. Ali talked a streak about civil rights; Frazier didn't mention them much. But it was he, the sharecropper's son, who had felt the sharper edge of segregation, “the animosity, hatred, bigotry, you name it”. He punched his bag at home because the town

playgrounds were closed to him. From childhood he picked okra for white farmers until one day he defied them, threw in his job and left the South on a Greyhound bus, already sure at 15 that he could never make a life there.

Buying the plantation

He enjoyed his celebrity time: the fur coats and the diamond rings, the maroon Cadillac limousine in which her Billy Boy swept back into Beaufort to buy a 368-acre plantation for his mamma. He would joke and sing at the drop of a hat (stylish hats, too), heading a musical revue for some years called Smokin Joe Frazier and the Knockouts. Generally he rolled with the punches, a gentleman

when it counted. When George Foreman knocked him down six times in 1973 and took the world title from him he could only say, laughing, that Foreman punched good. Very good.

With Ali it was a different matter. They fought three times, and he lost twice. On the third occasion, the “Thriller in Manila” in 1975, when they pulverised each other in smothering heat until he could no longer see Ali's right coming and was stumbling round blind, his trainer pulled him out in the 14th. He never forgave him. Ali was spent too, Frazier still wanted “to show him the error of his foolish pride”, and who knows what his left hook could have done to that pretty face. “How much did you want that title?” he was asked later. Beaming, he replied: “Like hogs love slop.” In his last years the money seem

ed to vanish; none was left for his funeral. His gym became a bedding outlet, and at the Spring Garden Deli, where he went to eat his lunch of grits with spinach and tomatoes, the waitress didn't know who he was. Gamely, he would let her beat him at arm-wrestling. And he could still be induced to sing sometimes, in a voice slurred and croaky after hundreds of

punches to the head, his own version of his favourite song: “I fought them fair, I fought them square, I fought them my-y-y-y way.”

例2:

Braveheart of darts

Jocky Wilson, darts player, died on March 24th, aged 62

?

?

OVER the centuries the Scots and the English have pounded each other with

arrows and claymores, cannon and guns. They have clashed on windswept moors, in lowering glens, 'mid swirling mists and up to their knees in the waters of the Tweed. They have done so almost as famously at Jollees Cabaret Club in Stoke-on-Trent and the Lakeside Country Club in Frimley, where the battledress was not steaming tartan but bulging, shiny nylon shirts; where the smoke belched not from artillery, but from chain-smoked Players and Dunhills; and where the weapons of choice were not swords or pistols, but tiny steel-tipped weapons forged of tungsten and flighted with plastic feathers.

Jocky Wilson flew the flag that way for more than 15 years. (He sometimes did so literally, pushing his grinning way through the crowds with the Saltire clasped in one plump hand.) He became the first Scot to win the Embassy World

Professional Championship in 1982, repeated the feat in 1989, and between 1979 and 1991 he always reached at least the quarter-finals. In that golden age of darts, when the sport was swept from its pub origins to become a gladiatorial

televised spectacle second only to soccer, he was a favourite on both sides of the border: the “wee hero” from grim grey Kirkcaldy, tiny and round, with a broad pasty face, a wide smile and a pint of lager in his hand. “Jocky” rhymed usefully with “oche”, the throwing line where he would stand, sweating liberally and

swaying slightly, aiming at the board with a snatch of his fingers and a pursing of his lips, as if to kiss each dart goodbye.

Most of his rivals were English. He beat John “Old Stoneface” Lowe to become world champion in 1982, and clinched victory in 1989 against Eric “The Crafty Cockney” Bristow. Playing the English always tanked him up, and brought out the Scot in him. He was raised on his grandmother's tales that the Auld Enemy had poisoned the water in Kirkcaldy and elsewhere; he therefore seldom brushed his teeth, and by the age of 28 had none, thanks to English treachery. (A well-done steak he could manage, even apples; but nuts put him in mind of Flodden field.) It gave him a low but definite pleasure to kick Mr Bristow hard in the shin just before their world championship encounter, sending him on to the stage hobbling and bleeding through his red English trousers, for no holds were barred against Sassenachs even when they were his friends.

He was lucky to win that match at all, and he almost lost, letting a 5-0 lead drift to 5-4 before he nailed it, on the third throw, with a double 10. But then, for all his accuracy and arcing, tiptoe artistry, cigarette in one hand and dart in the

other, he often threw games away altogether: once so drunk that he could hardly walk, and another time sealing his defeat by toppling off the stage. Small wonder, when he would fuel himself with seven pints of lager and his “magic” Coke,

swigged from a litre bottle topped up with vodka, to “get his nerves in shape”. It was hell when his manager would lock him in a room before a match with just a couple of weak beers and a pie; it was worse when he got diabetes later and had to drink nothing but water, for he couldn't function at all then, and in 1996 gave up darts altogether. He showed, by joining the breakaway World Darts Council

and appearing on video attempting star-jumps with leotarded lovelies, that he approved in principle of a sleeker, soberer version of the sport. In practice, though, he was never going to make it, not in a million years.

The Butlin's moment People called him a character and loved him for it, but that character was hard won. Because his mother could not cope with her many children, he spent 14 years in a children's home on the grey North Sea in Elie; his brother Tom was

abused by the principal, though all Jocky had to say about it was that he had won the pole-vault there. A spell in the army was followed by drudging poverty:

digging and delivering coal (he was black as a sweep when he first met his wife Malvina), chopping the fins off fish, Malvina picking potatoes when he had no work. Darts were a way to get shillings in pubs to buy a pint. But he practised until he was good enough to win £500 at the Butlin's holiday camp in Ayr, and found a job for life.

The winnings poured in as he toured round the country in his Volvo and his caravanette. Then they poured out again. He bought a £40,000 bungalow in a nice part of Kirkcaldy, but filled the garden with empties until the neighbours asked him to move. More than £1,000 of his world-champ earnings went on a pair of false teeth, but he never got on with them, and would take them out

publicly to play. He bought a fishing boat in which he would escape, disguised in a bobble hat, out into the Firth of Forth, but had to sell it, and ran up tax bills he never expected. He played his last match, like his first, at Butlin's, and ended his days on benefit in a tiny council flat, much as he had started.

And yet when darts fans thought of Jocky, what they remembered was his smile: huge, toothless and ecstatic, with his pudgy arms raised in victory on either side. It was the smile of a man who has triumphed over considerable odds; and also the smile of a Scot who has just whumped an Englishman.

例3:

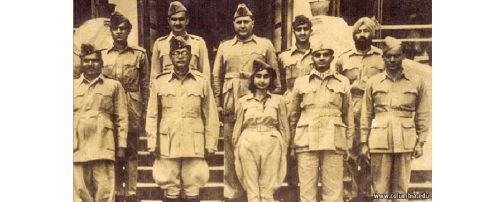

Captain Lakshmi

Lakshmi Sehgal (“Captain Lakshmi”), doctor and fighter for Indian independence, died on July 23rd, aged 97

?

AS SHE moved, pert and bird-like, round her tiny rented clinic in industrial

Kanpur in northern India, Lakshmi Sehgal made her patients feel completely safe in her hands. Lightly but firmly, her fingers moved across the swollen bellies of pregnant women, or felt for a pulse, or probed a wound. Her sister said she had always had the technique to reassure. Those same hands, in West Bengal in 1971, had massaged the scrawny limbs of Bangladeshi refugees, and in December 1984 had soothed the burning eyes of victims of the explosion at a chemical factory in Bhopal.

They also knew how to fire a revolver and prime a grenade, change the magazine on a Tommy gun and wield a sword. They were as skilled and ruthless as any man’s, for Dr Lakshmi had been trained beside the men to become a killing machine. From 1943 to 1945, in the jungles of Singapore and what was then Burma, she commanded a brand-new unit of the Indian National Army in the hope of overthrowing the British Raj. The Rani of Jhansi regiment, set up by the independence leader Subhas Chandra Bose (left of her, above), was for women only, the first in Asia. It was named after a heroine of the 1857 Indian rebellion against the British, a widowed child bride who cut her saris into trousers to ride into battle. For Dr Lakshmi, another rich tomboy who had married too young, a rider of horses and driver of cars who had eagerly thrown her foreign-made dresses on a nationalist bonfire, the rani made an irresistible model.

Bose, too, was irresistible. She had first seen “Netaji” at 14, in 1928, when she was taken to Calcutta to the assembly of the Congress party by her activist mother. He strode in uniform at the head of his party volunteers, bravely

rebellious, his owlish glasses glinting in the sunrise. Fifteen years later, when she had fled to Singapore with a new lover to set up a free clinic for Indian migrant workers, they met again. Bose persuaded her to recruit Indian women from the

diaspora in Malaya and Singapore to fight for the cause: to link up with the Japanese, invade India through Burma, and seize the capital. He made her a colonel, although she was always “Captain”. A fine singer, she had already recorded the army song: Chalo Dilli, “On to Delhi!”

As a native of Madras (now Chennai), whose soft voice still kept the lilt of Tamil, she was used to heat, but not to privation. Wearing the same sweat-soaked khakis for days on end was torture. Nonetheless, she cut an almost fashionable figure, and would take the salute in stylish sunglasses. Many of the troops she commanded were single teenage girls from the Malayan rubber plantations,

giggling and shy. They all trained hard, but to her intense frustration they were deployed as nurses and never went into battle. Bose’s campaign ended in the spring of 1945 with a 23-day retreat through the Burmese jungle under monsoon rains, the leader solicitously shepherding his women soldiers, and Colonel Lakshmi once more a doctor to his horribly blistered feet.

A dream of free women

Looking back on it later, she felt the whole freedom struggle had gone wrong. Partition had been a disaster, and the modern pursuit of money had ruined what was left. Blunt-spoken and practical, she denied having dreamy ideals for an

independent India; but she had had many. As the only woman in the short-lived cabinet of Bose’s Provisional Government of Free India, she hoped to abolish child marriage, dowries and the ban on remarriage of widows. She wanted women to have chances like hers: to be educated, self-supporting if they cared to be, and able to make their own choices about marriage. Beyond that, she hoped for an end to all the divisions in India, between rich and poor, men and women, castes or religions. She would rush to help people, carrying clothes and medicine, whatever their tribe or creed. When Indira Gandhi was murdered by her Sikh guards in 1984, she interposed her small body to save Sikh shopkeepers in her street; when the Ayodhya mosque was destroyed in 1992, she rebuked Hindu neighbours who were dancing in celebration.

As a girl, she had got into communism by reading Edgar Snow’s “Red Star over China” and by talking through the night with some of India’s first women communists. In 1971, encouraged this time by her daughter Subhashini, she joined the party’s Marxist branch, and felt she had come home. Still moved by Netaji’s fighting spirit, and still hungry for an egalitarian India, she went into

politics, getting as far as the upper house of Parliament. In 2002, at 87, she was the candidate of four far-left parties for India’s presidency, running on a single theme: the unity of the country. She was pummelled, but it didn’t matter. She had made her case and, just as important—for she was always a doctor first—she had not neglected any of her patients.

Every morning, until the day before her heart attack in July, she went to the clinic at 9am. Since she charged almost nothing, there were always many more

patients than she could see. Before she opened up, she would personally sweep the street in front of the place, to clear away the litter the neighbours threw out of their windows. Someone lower-caste could have done it for her. But it was a small gesture, with her own hands, towards the sort of India she would have liked to see.

例4:

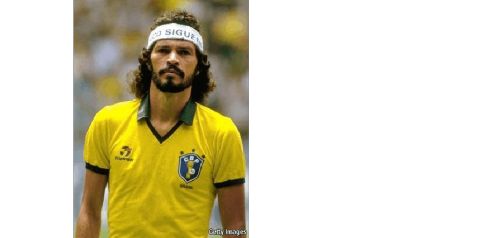

Sócrates

Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira, Brazilian footballer and political agitator, died on December 4th, aged 57 Dec 10th 2011 | from the print edition

?

?

ONE was short, fat and famously ugly; the other was handsome, slim and very tall indeed, with tumbling dark curls caught back in a headband. One skulked

about in a grubby robe and sandals; the other shone in blue micro-shorts and the sun-yellow shirt of Brazil. One wandered round the market place, teasing out the Good with onslaughts of severely logical questions. The other played football; and that was pretty good, too.

The fact that both men were called Socrates was not the only link between them. For the one born in Belém do Pará, at the humid mouth of the Amazon, was also an intellectual. In a sport in which most players' brains soon take residence in their boots, he talked of Van Gogh and Cuban history, practised medicine and worried about democracy. Over a career that included almost 300 games for his main club, Corinthians of S?o Paulo, and 60 games for Brazil, he trod the pitch as a man of thought, reading the game like a mathematician before, almost

nonchalantly, applying some genius touch.

Whether this love of wisdom had soaked in with the baptismal water, or whether he had picked it up in the library proudly assembled by his self-taught father (who also named two of his brothers Sófocles and Sóstenes), no one knew. He himself said his childhood heroes were Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and John

Lennon. Yet his book, “Football Philosophy”, ended with a maxim that would have pleased his namesake: “Beauty comes first. Victory is secondary. What matters is joy.”

He meant what he said. He was never in a team that won the World Cup (though Brazil has done so five times); but then the relentless focus and discipline required to lift that trophy never pleased him. Like his namesake, he sought

Beauty. And spectators found it whenever he played, with his elegant gazelle runs, his leaps and accelerations, his classy back-heels and his long, loping passes from midfield. There were few keener reminders of the Beautiful than the game against Italy in the 1982 World Cup, when he was captain: a game of surpassing skill and spontaneity capped by a wonderfully deceptive goal of his own, almost disguising the fact that Brazil then lost and left at the second-group stage.

A gadfly in boots

Yet Dr Sócrates, as Brazilian fans called him, never put football first in his life. Early on he would miss training sessions if they clashed with his medical studies. In a country that eats, breathes and lives football, where commerce stops for it and elections are planned by it, he insisted that the most vital thing was to get rid of poverty, build roads and schools and, not least, teach manners. His namesake would have called this pursuing the virtuous life. He called it “prioritising the human being”. The best thing about football, he said once, was the ordinary people he met—including those of Garforth, near Leeds in northern England, whose non-league team he coached for a chilly month in 2004.

He also spoke up for the common man. Like the first Socrates, he saw himself as a gadfly of the tyrannical, lazy or self-satisfied. He disliked the way Corinthians was run, with management treating players like children, and organised a system where everyone in the club, from kit-boy to president, would vote about the length of training and the time of lunch—hoping, no doubt, for greater laxity about parties and smoking and beer, all of which he found essential to his own

free-ranging game. (“I am an anti-athlete,” he explained. “You have to take me as I am.”)

He disliked the way Brazil was run too, under a cohort of generals after a coup in 1964; he pestered for free elections by leading a Corinthians team with

“Democracia” printed on their shirts, and by marching off in 1984-85, when

Congress failed to pass the necessary laws, to play for Fiorentina in Italy. If this was subversion and “corrupting the youth”, he revelled in his dangerous influence. And he didn't let up: Lula was good, he said, but earned a mere seven or so out of ten for how he had governed Brazil. For Sócrates only outright revolution, Fidel-style, rated a ten.

Retired from football, he continued to campaign against the corruption rampant in the game. He demanded open elections—by players, fans, everyone—for the top job in the Brazilian Football Confederation, and toyed with fielding his team-mate Zico against the scandal-tangled president. He began to write a novel, set during Brazil's hosting of the World Cup in 2014, in which public money was yet again disappearing into private pockets, and white-elephant stadiums were rising across the land. He saw no change in prospect. His own Corinthians, once struggling, were rolling in money, but he preferred his political slogans to the dozens of

sponsors now blazoned on their shirts. And he would rather have seen a creative defeat than the ill-tempered game that made them national champions a few hours after his death.

He died too young, after a dinner with friends which his weakened liver couldn't take. But he always needed to set Brazil to rights over copious cacha?as at some café table: his own “Symposium”, where ideals would be pursued through smoke, alcohol and argument. As a doctor and ex-midfielder, he knew he should not have done it. As a philosopher, he sealed his death warrant with his usual wit and serenity.